Peter Bleksley: ‘Policing Brixton riots was a battle for survival’

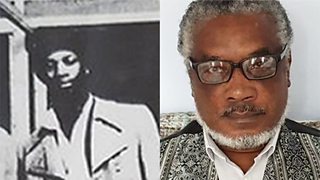

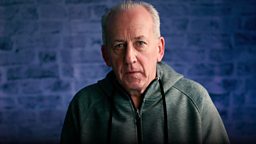

In the late 1970s, Peter Bleksley was a rookie PC based at Peckham Station in London and in the 1980s he became a founder member of Scotland Yard’s undercover unit.

Today he is a broadcaster and author.

On the evening of Friday, April 10 he was sent to police the Brixton riot.

“We had a very long, exhausting week, so we dropped many of our colleagues off early. By the time the shout went up for urgent assistance in Railton Road, there was only about three or four of us in the van. We said, yep, we'll have some of that.

All we became was a very red rag to a very angry bull"Peter Bleksley

We tore down the road, piled out of the van, and already you could feel the tension.

I was told that a young black man had been stabbed in the back and a police officer, in an effort to stem the bleeding, had knelt on his back, putting his knee over the wound.

Because of the heightened tension courtesy of Operation Swamp [a stop and search operation in Brixton] this could be misconstrued. And so it started to kick off.

It wouldn't have taken very much for that Friday night to have exploded. But we held our ground until we were called off the streets and told to go to Brixton police station and wait in our vehicles.

We were specifically told not to get out of our vehicles, not to stop anybody, not to search anybody, but just patrol endlessly.

All we became was a very red rag to a very angry bull. We saw a man coming out of a basement carrying a crate full of empty milk bottles. We knew exactly what was going to happen. They were going to be made into petrol bombs.

And the following day, it was just utter pandemonium, Brixton burnt, hundreds of cars overturned, the pub set on fire.

It felt like it was them or us. It was almost a battle for survival."Peter Bleksley

It was, quite frankly, terrifying. And unforgettable. We lost all the windows in our van. So we wrapped our truncheons around our wrists. We got our heads down beneath the level of the windows. And we deliberately drove into crowds with our truncheons outside and you could feel them hitting things. I suspect they were probably people's heads, but we didn't care.

It felt like it was them or us. It was almost a battle for survival.

Virtually every shop had its windows smashed in and stuff was stolen. It was chaotic. Cops were running down the street trying to catch looters. How nobody got killed is miraculous, because I could see it in people's eyes. The anger. They actually wanted to kill me because of the uniform I wore and what I represented, a symbol of oppression, repression, perjury, violence. And it was utterly terrifying.

I’d had no experience of petrol bombs before, and to see one of those flaming bottles launching its way towards you when you have no flameproof clothing was a pretty terrifying thing. I didn't want to get out of our van. Despite the fact it had no windows, I still felt it was probably the safest place we could be.

We had utterly lost control. Ken Livingstone [Ken Livingstone became leader of the Greater London Council in May 1981 – one month after the riots and later became an MP and Mayor of London] said that the police got a bloody good hiding. And it was a very unpopular comment, but it was true.

They outflanked us; they outmanoeuvred us. The [police] leadership left a lot to be desired. The tactics were virtually non-existent. This was an utterly unprecedented situation. The UK had never seen rioting like this ever before, and it was a dark, miserable, scary, horrific time.

We eventually got stood down on Saturday night around about 10 o'clock. And I had never been so glad ever to be told I could go off duty.

Brixton High Street appeared to be wrecked. Railton Road appeared to be littered with burnt out cars and burnt out buildings. A lot of police officers were getting injured and we felt it was probably only a matter of time until people started getting killed.

A point had been made very, very clearly. The streets did not belong to the police. The suppressing and repressing of a sizeable Afro-Caribbean population in Brixton was done for. It hadn't worked. Look what they had achieved – nothing. Apart from rioting on a previously unseen scale.

Quite frankly, we got what we deserved'Peter Bleksley

The unscrupulous and unlawful practices of the police in terms of fitting people up, beating people up, stopping and searching people without any justification, led to the riots in Brixton of 1981.

Greater minds than mine should have seen this coming, but they buried their heads in the sand.

Quite frankly, we got what we deserved.

I became a much, much better human being, courtesy of the Brixton riots in 1981, because after that weekend when I got home that Saturday night I looked myself in the mirror. I vowed that I was never going to wear that uniform again.

I didn't want to be that symbol of oppression or repression. That weekend changed me forever for the better. And I have not been that vile, racist thug, I am pleased to say, for 40 years.’

As told to Ben Robinson

In April 1981, Brixton suffered particularly high rates of unemployment, poor housing, and crime. Swamp 81, a plainclothes police operation to reduce crime in Brixton, was launched in the area ten days before the riots.

Its use of stop and search raised tensions with the community, who felt young black men were being harassed.

The Metropolitan Police say that, over the years, the force has undergone enormous change, and it is a different force to the one it was 40 years ago. Their current commissioner says that racism will not be tolerated.