The strange true story behind The Da Vinci Code

Twenty years ago The Da Vinci Code gripped the world with the notion that Jesus Christ married, had a secret honeymoon in France and sired a hidden line of future European rulers. You probably know the story. After all – Dan Brown’s conspiracy thriller sold 80 million copies within five years of its release and spawned a film franchise.

But the story you may not know is that key parts of the theory have their origins not in the archives of The Vatican, but in the vaults of the 大象传媒. Kevin Core, producer of Seriously's Archive on 4: The Holy Blood, tells us the story of the fraud that sparked a conspiracy movement.

The dubious paperback

Gérard de Sède was a French journalist and novelist. His son would go on to describe him as a man with an eye for mischief, who when working for the French national press agency, made up a story about an eagle abducting a child.

In 1967 Gérard published a book called Le Trésor Maudit (The Accursed Treasure). The book followed an investigation into a rural priest from the tiny French commune of Rennes-le-Château. This priest had somehow spectacularly refurbished his local church using money from – as it turns out – ancient hidden treasure. Supposedly based on a true story, the book featured many elaborations and inventions, including “coded parchments” allegedly discovered by the priest but later proven to be forgeries. In true Da Vinci Code fashion, it said the parchments hinted that the ancient French king Dagobert II had not actually been killed in the 7th century, and that his descendants were waiting to be restored to the throne of France by a secret society called the “Priory of Sion”. There was no historical evidence for this shadowy organisation before it was invented by a collaborator on the book, the convicted fraudster Pierre Plantard.

A hit '70s TV show

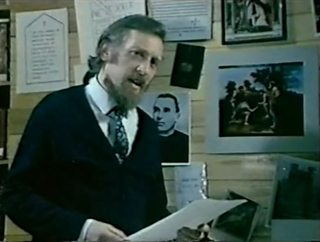

The Accursed Treasure resided in relative obscurity until a former Doctor Who screenwriter named Henry Lincoln picked up a copy while on holiday in 1969. Lincoln was hooked – so hooked that he pitched it to the 大象传媒 and in 1972 the story was told on air as part of a factual history series called Chronicle. Alongside creepy organ music, arcane codes and pentangles overlaid on surrounding topography, the series cast Henry as a professorial truth-seeker on the verge of a world-shattering discovery. The retelling of the mystery and the hidden lineage was a huge hit, even prompting viewers to head to the South of France to solve the conundrum for themselves. By the third episode, Lincoln had been joined in his research by two writers named Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh – whose involvement was about to take the conspiracy to a whole new level.

The bestseller before Da Vinci Code

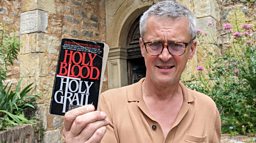

Inspired by the success of their TV series, Lincoln, Baigent and Leigh wrote up their research in a book called The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. The book was a dense retelling of the village mystery – but it went a step further. It popularised the theory that Jesus married Mary Magdalene and did not in fact die on the cross. It was this secret, they wrote, that was being protected by the shadowy Priory of Sion.

On the verge of the book’s publication in 1982, the three authors appeared on the arts programme Omnibus and were torn to shreds in a televised debate. Young historian Marina Warner savaged the book’s lack of evidence. Warner pointed out that if their source about Mary Magdalene’s trip to France was accurate, they must also believe that an angel descended from heaven at the martyrdom of St Catherine of Alexandria and killed thousands of spectators (they’d left that bit out of the book).

However, one early review of the book was prophetic. Popular author Anthony Burgess said, “It is typical of my unregenerable soul that I can only see this as a marvellous theme for a novel.” The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail became a bestseller.

The Dan Brown court case

There is no doubt that The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was a major influence on Dan Brown’s 2003 mega-selling novel The Da Vinci Code. The name of central character Leigh Teabing is even an anagram of Baigent and Leigh. The astonishing success of the thriller saw the two writers undertake an ill-advised plagiarism action against Dan Brown’s publishers, despite Da Vinci mania giving them a considerable sales boost. For observers in the know, the case was unwinnable. Either the story was their property (meaning they had made it up) or it was history (and was therefore in the public domain). Despite not taking part in the action, losing the case cost Henry Lincoln, as court fees were taken from the royalties of all three.

A template for conspiracy

Watching it back now, the TV phenomenon Chronicle, with all its ’70s stylings, looks extremely dated. But there's a remarkable similarity between the series and other conspiracy theories that have gained traction since the show first aired – they are a lot of fun to put together. Whether talking about faked moon landings or microchips in vaccines, making spurious connections and sharing them with others equally despairing of the mainstream media is a process that draws people in. However damaging, those involved feel part of a community. For Dame Marina Warner, the historian who originally debunked The Holy Blood in the 1982 TV debate, the attraction is clear. “This is the classic structure of a conspiracy theory,” she says, “You take random elements. you put them together and you make a coherent shape. We are pattern-seeking minds.”

To hear more about this amazing story, listen to Archive on 4: The Holy Blood on Radio 4’s Seriously.

More from 大象传媒 Radio 4

-

![]()

Archive on 4: The Holy Blood

Hugh Schofield investigates how a forgotten 大象传媒 documentary supercharged a conspiracy theory.

-

![]()

Six things you need to know about deepfakes

The risks deepfakes pose to democracy, and their potential in health care.

-

![]()

The Truth Police

Meet the outsiders detecting fraud, malpractice and incompetence in science.

-

![]()

Marianna in Conspiracyland

What happened to the people who fell down the rabbit hole into a world of conspiracy theories?