How do we send a message to the far future?

How do we send a message a hundred millennia into the future to warn our descendants of dangerous nuclear waste buried deep underground? In this article poet Paul Farley – presenter of Radio 4 documentary The Nuclear Priesthood – writes about the fascinating potential solutions to this problem.

Over the past decades we’ve stockpiled a legacy in the form of nuclear waste. Our responsibility to future generations presents two major challenges. First, finding a place to dispose of this high-level nuclear waste. The current consensus is that burying the waste deep underground in geological disposal facilities (GDFs) is probably the safest option. But time is the second challenge here. It takes tens of millennia for high-level nuclear waste to decay to a point where it’s safe. So how do we warn our descendants hundreds – maybe thousands – of generations from now of the dangers of the waste we’ve buried?

Do signs keep their meaning?

A clip from The Nuclear Priesthood on 大象传媒 Radio 4.

Nuclear semiotics

What elements of communication might we still have in common with our distant descendants?

An international coalition of nuclear engineers, physicists, anthropologists, linguists and artists have been thinking about how to warn future generations about our buried nuclear waste.

The technical term for all this is "nuclear semiotics" – semiotics being the study of how signs and symbols convey meaning – and at its heart it’s about communication. What elements of communication might we still have in common with our distant descendants? The materials deep underground may be going through radioactive decay, but how do we prevent our memory of those materials from decaying?

Disappearing ink

A message written in the English language of a thousand years ago would be largely indecipherable to all but a few scholars and specialists. Where do you start with a written message which must last a hundred thousand years? If you were to gaze into deep time in the other direction and look back over the same timescale, it would be like asking Neanderthals to compose a message which is still clearly comprehensible today!

Visual warnings

The nuclear trefoil is that triple-bladed, yellow-and-black symbol we all associate with radioactivity… Or do we? Well, a survey by the International Atomic Energy Authority revealed that in some countries as few as six percent of people knew what the trefoil meant.

Pictures and symbols are ambiguous, and their meaning also changes over time. Maybe the burial sites themselves should be off-putting?

Hostile architecture

The builders of the Egyptian pyramids meant them to be left undisturbed for eternity. Their treasures are now scattered across the world in museums.

Some agencies in charge of buried nuclear waste have suggested using unsettling structures to deter future visitors. Imagine a field of giant spikes, jagged concrete lightning bolts, a landscape of thorns. Wouldn’t this say "KEEP OUT" to any curious descendant? Perhaps not. The builders of the Egyptian pyramids meant them to be left undisturbed for eternity. Their treasures are now scattered across the world in museums. From childhood, the more we’re warned not to do something, the more we want to do it. And there’s no reason why our descendants won’t feel exactly the same. So perhaps we need to embrace that curiosity?

Informing and warning

Jean-Noël Dumont is head of the Memory Programme at the French nuclear agency, Andra. He explains that, “We are no longer in this idea... of creating fear in order to deter people. We are more in the idea of informing.” Dumont is particularly interested in the ideas that artists can bring to nuclear semiotics – like Aram Kebabdjiam and Stéfane Perraud, who create what they call "multimedia narrative machines", and came up with the idea of the Blue Zone to mark the site of a GDF, a concept where a forest growing above nuclear waste would be genetically modified to be completely blue.

Glowing cats

Back in the early 1980s the US Department of Energy convened a team of engineers, anthropologists, nuclear physicists and behavioural scientists to address the challenge of communicating with the future: the Human Interference Task Force. One of this organisation's ideas was to breed "ray cats": cats which would change colour – maybe to green or blue – when near any radioactive material. Cats were chosen because they’ve been our familiars for thousands of years. And these cats’ importance would be sewn into our collective awareness by fairy tales or myths.

A nuclear priesthood

Another solution came from semiotician Thomas Sebeok. In a 1984 report titled ‘Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia’, he proposed the idea of a nuclear priesthood whose role was to keep alive the knowledge of the nuclear repository yet to steer the uninitiated away from it.

More recently, the artists Robert Williams and Bryan McGovern Wilson used Sebeok’s proposal to inform their Cumbrian Alchemy project. They imagined the vestments a nuclear priest might wear: the kind of light business suit and fedora hat worn by Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Research Laboratory where the first atomic bomb was developed; and also a silvery mask based on a third-century Roman cavalry helmet that had been discovered in Cumbria.

The Edge of Memory

Could we pass on the warning or knowledge about buried nuclear waste not through pictures or symbols or anything written down but simply by telling each other stories about it? It may seem a very high-risk or fallible way to pass on information.

For his book The Edge of Memory, Professor Patrick Nunn from the University of the Sunshine Coast has been researching Indigenous Australian stories which seem to record an ancient inundation dating back to the end of the last ice age. “We know that all these stories must be at least seven thousand years old," says Professor Nunn, "passed down along hundreds and hundreds of generations in intelligible form to reach us today”.

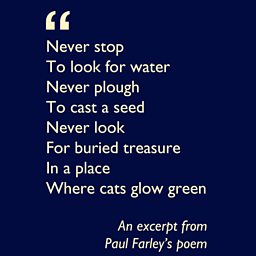

An atomic poem

The search isn’t just about a message for the future. It’s also about talking to each other right now about our nuclear legacy. “We need to think about the nuclear present and our current responsibility,” says Dr Ele Carpenter. “The contemporary thought is that knowledge of nuclear sites needs to be embedded in culture in a whole range of different ways.” According to Jean-Noël Dumont, “The solution, if there is one, is a network that will reinforce itself.”

While making the documentary The Nuclear Priesthood I made a poem, using ideas encountered when talking to people and visiting places. For maximum mnemonic power, a "sticky" poem needs to be brief and lyrical, so this one sports a simple sound pattern, with the rhyme turned up to 11… I don’t doubt most listeners will have forgotten it by the time The Archers goes out! But maybe it could contribute in some tiny way to a collective memory.

To hear this poem in full and learn more about the amazing world of nuclear semiotics, listen to The Nuclear Priesthood.

More from Seriously

-

![]()

The Nuclear Priesthood

Poet Paul Farley considers how we warn future generations about our buried nuclear waste.

-

![]()

Lights Out: Fallout

Exploring the legacy of the UK's atomic testing programme in the South Pacific.

-

![]()

Does time move faster as we get older?

What are the emotional, physical and cultural factors which affect our perception of time?

-

![]()

Do our cats judge us?

Comedian and cat owner Suzi Ruffell investigates the behaviour of our feline friends.