Ming banknote

Neil MacGregor's world history as told through objects. Today - one of the world's earliest paper bank notes made in 14th Century Ming China.

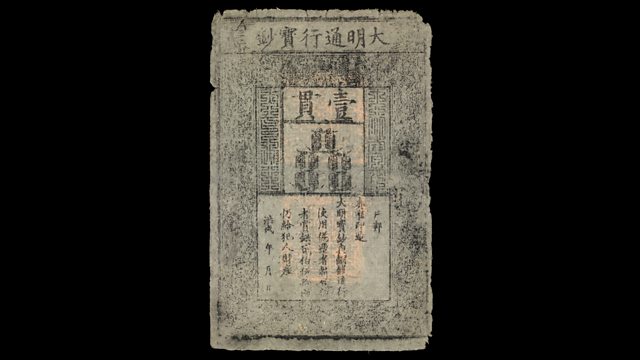

This week Neil MacGregor's history of the world is exploring the great empires of around 1500 - the threshold of the modern era. Today he is in Ming Dynasty China and with a surviving example of some of the world's first paper bank notes - what the Chinese called "flying cash". Neil explains how paper money comes about and considers the forces that underpinned its successes and failures. While the rest of the world was happily trading in coins that had an actual value in silver or gold, why did the Chinese risk the use of paper? This particular surviving note is made on mulberry bark, is much bigger than the notes of today and is dated 1375. The Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, and the historian Timothy Brook look back over the history of paper money and what it takes to make it work.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to money, trade and travel.

About this object

Location: China

Culture: Ancient and Imperial China

Period: AD 1375

Material: Paper

��

This Chinese Ming dynasty banknote is inscribed with the title Great Ming circulating treasure note and a warning that counterfeiting is punishable by death. Paper currency was first used in China as early as AD 1000. However, the Ming were the first Chinese dynasty to try to totally replace coins with paper money. The state issued too much paper money, however, causing hyper-inflation. By 1425 paper money was worth only a seventieth of its original value and the use of paper currency in China was suspended.

Who were the Ming dynasty?

This banknote was commissioned by, Zhu Yuanzhang, the first Ming emperor. In 1368 he took part in the rebellion to overthrow the Mongol Yuan dynasty that ruled China. China enjoyed a long period of stability under the Ming dynasty (1368 - 1644). Many of China's ancient traditions were restored but China also pursued an expansionist foreign policy. Expeditions were sent across the Indian Ocean to India, the Middle East and East Africa. The introduction of yams, maize and potatoes by the Spanish and Portuguese allowed Ming China's population to double to at least 100 million.

Did you know?

- A message on this banknote reads 'to counterfeit is death'.

Is evil the root of all money?

By Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England

��

This is many hundreds of years old, but in many ways it’s remarkably modern. It’s bigger than a banknote would be now – it's A4 sized – but actually it encompasses everything the modern banknote has, which is the visible stamp of authority of the state. And that has become crucial to people accepting paper money.

Money could be private currencies, there were in fact many attempts to initiate private currencies, they tended to break down. Why? Because the money itself was an attempt to be a substitute for promises to pay later; they wanted something in the hand now. If you had your harvest you were bringing to market you didn’t necessarily want to swap it for something immediately, but you wanted purchasing power which you could retain to buy something later. But it had to be in a form that you could guarantee that it would be usable. And promises of credit often broke down – people broke their word.

That’s why I think in someway the right aphorism is that ‘evil is the root of all money’!

Money was invented in order to get round the problems of trusting other individuals. But then the issue is could you trust the person issuing the money? And you can imagine a world with many private currencies, but what we all want is something that we can all recognise as money; we don’t want to have to go around judging whether your money is worth more than somebody else’s. So the state became the natural issuer of money.

And then the question is can we trust the state? And in many ways that’s a question about can we trust ourselves in the future. And what went wrong for the Ming dynasty was that although they were an empire with a bureaucracy, the one bit of the bureaucracy they didn’t have was an institution to manage the paper money.

The Ming dynasty

By Timothy Brook, Shaw Professor of Chinese Studies, University of Oxford

��

China in the thirteenth century was the largest state and the largest economy anywhere in the world. And then the Mongols invaded in the 1260s, but they prove remarkably incapable of ruling the country, and after a century the country sinks into civil war. Out of this emerges the Ming dynasty in 1368.

The man who brings the dynasty into being is a peasant refugee by the name of Zhu Yuanzhang. He is also a very clever strategist, and after 15 years of civil war he emerges as the new leader in 1368 and decides to try and put China back to where it was millennia ago. He wants to recreate a stable agricultural, rural world. He wants to move away from the wild commercial vision that the Sung and the Yuan dynasty had embraced. Then curiously it slips away from him and the Ming dynasty will in turn become the largest commercial economy in the world.

People look back to the early Ming in two ways. In one way they don’t like it because the similarities between Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong are very close: somebody from a rural background who steps forward, organises a revolution and grasps power,and for many people in China today Chairman Mao is not a happy memory. Therefore Zhu Yuanzhang is a figure they’re a little bit anxious about. On the other hand there is a kind of fond memory of a period in which there appears to be stability. Of course, this is all retrospective: I don’t think life was any more stable in the fifteenth century than it is in the twenty-first. But it seems to be a period when the Chinese knew who they were, what their place in the world was, and it was a place about which they could feel confident.

Flying cash or worthless paper?

By Helen Wang, curator, British Museum

��

The origins of paper money lie in the ‘flying cash’ of Tang dynasty China (early ninth century AD). This was a perfect name for the certificates that were issued as part of a long distance remittance system. Tang dynasty China was a golden age, and a period of great activity on the Silk Road.

Merchants travelling to the capital city would deposit their coins with the government office representing their home locality, in exchange for a certificate (the ‘flying cash’), which they could later cash in with the provincial authorities when they returned home.

Just like banknotes today, the certificates meant that people didn’t have to carry around huge amounts of coins: the ‘flying cash’ was light, easy to carry, and easy to hide. There were also benefits for the issuers of the certificates, because it was cheap to produce and issue the certificates and it meant they always had access to ready cash in the capital city.

The certificates worked because there were advantages for everyone, and because people had confidence in the system. A win-win situation!

But paper money doesn’t always work. Ming dynasty banknotes, like this one, were first issued in 1375, and they were successful at first. But the notes were not convertible, so people could not cash them in. Naturally, people turned to what they believed in, which happened to be silver.

Eventually, the Ming government had to enforce the use of banknotes, in particular by insisting that people paid their taxes in banknotes.

Eight Ming dynasty banknotes found in tombs dating to the 1420s tell us of the chaotic financial situation in China at that time. The notes were placed there for use in the afterworld.

In the 1420s a note for one string of coins (that’s 1000 coins) was actually worth only 40 coins. The notes may have been almost worthless pieces of paper in the real world, but in the afterworld they could still represent 1000 coins.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Tue 14 Sep 2010 09:45����ý Radio 4 FM

- Tue 14 Sep 2010 19:45����ý Radio 4

- Wed 15 Sep 2010 00:30����ý Radio 4

- Tue 10 Aug 2021 13:45����ý Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Money, Trade and Travel—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to money, trade and travel.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects