Pardon for the Disowned Army

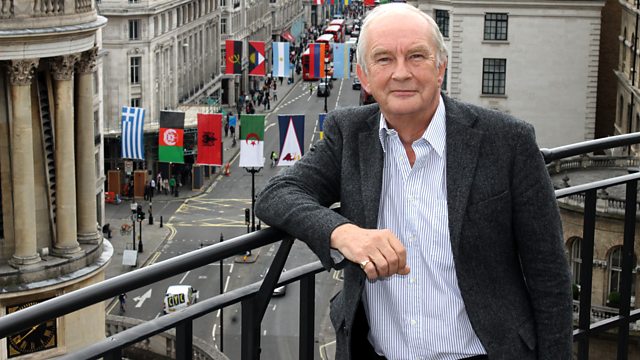

John Waite investigates the fight for justice on behalf of 4,500 Irish soldiers who were punished for deserting their own army to help fight fascism in the Second World War.

The thousands of Irish soldiers who swapped uniforms to fight with the British against Hitler went on to suffer years of persecution on their return home John Waite's first investigation into their plight, which was broadcast earlier this year, generated huge interest from listeners and was debated in the Irish Parliament.

This was the first broadcast to highlight the injustice they suffered and to hear from them about the on-going repercussions and their continued fight for a pardon.

The programme led directly to the Irish Minister for Justice, Alan Shatter, undertaking an urgent review and, just six months after the broadcast, he announced an official pardon.

As John Waite now hears, one of those relieved by the news is 92-year-old Phil Farrington, took part in the D-Day landings and helped liberate the German death camp at Bergen-Belsen. Up until now he has had to wear his service medals in secret after having spent time in a military prison in Cork for deserting the Irish army. He returned to a British unit on his release but has had nightmares that he would be re-arrested by the authorities and punished again for his wartime service.

"They would come and get me, yes they would," he said in a frail voice at his home in the docks area of Dublin. Mr Farrington was one of about 4,500 Irish soldiers who deserted their own neutral army to join the war against fascism and who were brutally punished on their return home as a result. They were formally dismissed from the Irish army, stripped of all pay and pension rights, and prevented from finding work by being banned for seven years from any employment paid for by state or government funds.

A special "list" was drawn up containing their names and addresses, and circulated to every government department, town hall and railway station - anywhere the men might look for a job. It was referred to in the Irish parliament - the Dail - at the time as a "starvation order", and for many of their families the phrase became painfully close to the truth.

John Stout served with the Irish Guards armoured division which raced to Arnhem to capture a key bridge. He also fought in the Battle of the Bulge, ending the war as a commando. On his return home to Cork, however, he was treated as a pariah. "What they did to us was wrong. I know that in my heart. They cold-shouldered you. They didn't speak to you.

It was only 20 years since Ireland had won its independence after many years of rule from London, and the Irish list of grievances against Britain was long - as Gerald Morgan, at Trinity College, Dublin, explains. "The uprisings, the civil war, all sorts of reneged promises - I'd estimate that 60% of the population expected or indeed hoped the Germans would win. To prevent civil unrest, Eamon de Valera had to do something. Hence the starvation order and the list."

Today, thanks largely to this 大象传媒 investigation, those Irish servicemen have at last been recognised for the part they played in helping defeat fascism.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Broadcasts

- Wed 8 Aug 2012 12:30大象传媒 Radio 4

- Sun 12 Aug 2012 21:00大象传媒 Radio 4