Politicians respond to the Saville report

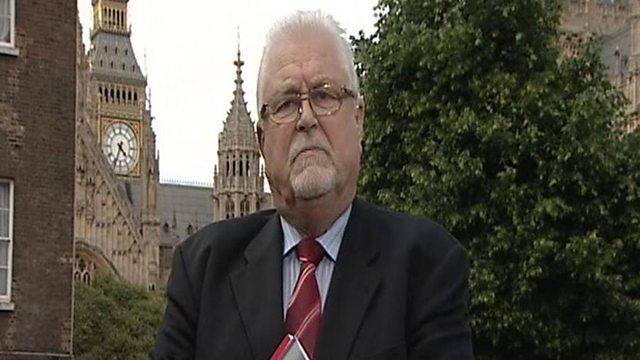

Stephen Farry MLA (Alliance), Dolores Kelly MLA (SDLP), Dennis Murray (former ����ý Ireland Correspondent) and Lord Ken Maginnis respond to Lord Saville’s report on Bloody Sunday.

On the day that Lord Saville’s report into the events of Bloody Sunday is published (please see context below) Jim Fitzpatrick anchors a special Stormont Live.

He is joined in the studio by Stephen Farry MLA (Alliance), Dolores Kelly MLA (SDLP) and Dennis Murray (former ����ý Ireland Correspondent).

Stephen Farry appreciates the hurts across society and the demands for truth and justice – but he feels that Bloody Sunday stands out and justifies having its own special inquiry because of the abuse of the rule of law.

Dolores Kelly feels that it is a day for the families; it is an historic day when the truth has come out. She hopes to see some form of justice done.

Denis Murray is struck by the unequivocal language in Lord Saville’s report. He notes the relief expressed by the victims’ families at the Guildhall. He does not see it as triumphalism – but he is sure that thousands of other families found it difficult to watch.

Stephen Farry would like to know what proposals the government will put in place for a comprehensive process to deal with everyone’s demands for truth in a manner that promotes reconciliation. He mentions the Eames Bradley report which he says is now parked. Eames Bradley refers to the report produced by the Consultative Group on the Past which was led by retired Archbishop of Armagh Lord Eames and Denis Bradley (who at the time of Bloody Sunday was a Roman Catholic priest attached to Long Tower Church in Derry).

Lord Ken Maginnis (of the Ulster Unionist Party) joins the discussion from Westminster. He is disappointed with Lord Saville’s report and in Prime Minister David Cameron’s response to the report. Lord Maginnis states that he admitted long ago that the deaths of the 14 people who died in Derry should not have happened, but it was difficult for the young soldiers who were introduced to urban guerrilla warfare without proper training: “Although the victims were not carrying guns, they had broken away from the legitimate parade – that’s admitted in the report – in order to confront the troops. I wonder what all the other 97 and a half percent of victims in 1972 feel about what has happened today in respect of two and a half percent of the victims”.

Correction: Ken Maginnis misinterprets Saville's findings. There was a breakaway from the main march, but Saville did not conclude that any of the dead or wounded had broken away from the march with the specific intention of attacking soldiers. The Saville report concludes in paragraph 3.76: “Despite the contrary evidence given by soldiers, we have concluded that none of them fired in response to attacks or threatened attacks by nail or petrol bombers. No-one threw or threatened to throw a nail or petrol bomb at the soldiers on Bloody Sunday.” And in paragraph 3.79: “… none of the casualties was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury, or indeed was doing anything else that could on any view justify their shooting.”

Lord Maginnis is critical of Lord Saville for not mentioning the Catholic RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) officer Sergeant Peter Gilgunn who was killed in Derry three days before Bloody Sunday, or Constable David Montgomery (Lord Maginnis mistakenly calls him David Armstrong) who was killed in the same incident by the IRA (Irish Republican Army). He is frustrated that Lord Saville did not take into account how the threat of death to the security forces, propagated by Martin McGuinness and people like him, raised the tension.

Lord Maginnis is concerned that the Saville Inquiry has created a hierarchy of victims: “If I was one of the 97 and a half per cent of families who lost somebody to terrorism then I would feel neglected, I’d feel I’d been wronged”.

Lord Maginnis objects vehemently to Jim Fitzpatrick asking him if he is standing over the unjustifiable killings perpetrated by the soldiers on Bloody Sunday: “I’ve made it very clear that I’m not standing over that, but I also know what it is to command young soldiers of 18,19,20 in an urban guerrilla warfare situation for which they haven’t been properly trained, for which they weren’t at that time properly equipped, where communications were faulty and begin to understand how fear and threats all come together in order to create this unfortunate situation. It should not close our eyes to the other victims – the other 3 and half thousand”.

CONTEXT

On 30 January 1972 soldiers from the 1st Parachute Regiment killed 13 innocent civil rights demonstrators in Derry.

The period from August 1971 to January 1972 saw a sustained campaign of anti-internment protests. On 22 January, John Hume led an illegal demonstration along Magilligan Strand just outside Londonderry, towards a nearby internment camp. The marchers were confronted by soldiers of the 1st Parachute Regiment who drove them off the beach using baton charges and rubber bullets.

It was these same paratroopers who were sent into Derry eight days later to deal with another banned protest. This march was organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). Some ten thousand people gathered in the Creggan estate and proceeded towards Guildhall Square in the centre of the city. The paratroopers had sealed off the approaches to the Square and the march organisers, in order to avoid trouble, led most of the demonstrators towards Free Derry Corner in the Bogside.

Groups of local youths (referred to by the security forces as ‘YDHs’ – Young Derry Hooligans) stayed behind at the Army barricades to confront the soldiers. The soldiers were ordered to move in and arrest as many of the rioters as possible. Just after four o'clock, the paratroopers made their move. What took place next was totally unexpected: the paratroopers opened fire on the crowd, killing thirteen men and injuring thirteen others; one of the injured died some time later.

The soldiers claimed that they had been fired on as they moved in to make arrests. As far as the people of the Bogside and further afield were concerned, the Army had summarily executed thirteen unarmed, innocent civilians. The Widgery Tribunal, which had been set up to investigate the circumstances surrounding the killings, later concluded that: ‘At one end of the scale, some soldiers showed a high degree of responsibility; at the other end.... firing bordered on the reckless’.

The Londonderry Coroner, Major Hubert O'Neill, did not share Lord Widgery's conclusion. At the end of the inquest in 1973, which is still seen by nationalists as a cover up for murder, O'Neill said, “It strikes me that the army ran amok that day and they shot without thinking what they were doing… I say it without reservation - it was sheer unadulterated murder”.

The British government later made out-of-court settlements with the bereaved families

In 1998 the Labour government launched an in-depth investigation chaired by Lord Saville of Newdigate. The Saville Inquiry, which was the most expensive investigation of its kind in the United Kingdom, reported in June 2010.

It concluded that none of the dead posed a threat and the actions of the soldiers were totally without justification. The Prime Minister David Cameron apologised on behalf of the nation for the “unjustified and unjustifiable killings”.

Duration:

This clip is from

More clips from Stormont Live Special - The Saville Inquiry Report

-

![]()

Publication of Saville Report

Duration: 11:42

-

![]()

Relatives of Bloody Sunday victims

Duration: 27:09

-

![]()

Early political reaction to the Saville report

Duration: 09:16

-

![]()

Interview with Tony Clarke

Duration: 03:41