On the trail of rare blood clots

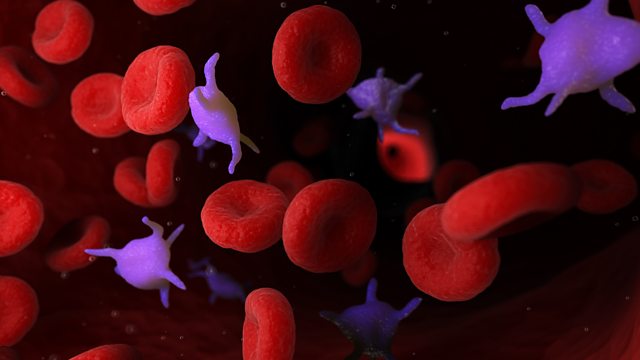

As medical agencies look out for any further cases of an extremely rare blood clot in vaccinated people, we hear from the haematologist who identified one of the first cases.

On Wednesday the EU’s EMA and UK’s JCVI announced a suspected correlation between vaccination and an extremely rare type of blood clot. Prof Sabine Eichinger is a co-author of a new paper suggesting a link with vaccination or the immune response to Covid vaccination and suggests the name VIPIT for the condition. One of her patients died at the end of February having presented with a rare combination of symptoms – blood clots and a low blood platelet count. Sabine tells Roland the dots they have managed to join in the story so far.

Scientists at Fermilab in the USA posted four papers and announced an exciting development in particle physics that might lift the curtain on science beyond the Standard Model. Their measurement of something known as g-2 (“gee minus two”, just fyi), by measuring with phenomenal accuracy the magnetic properties of muons flying round in circles confirms a 20-year old attempt at a similar value by colleagues at Brookhaven. At the time, it was breathtaking but suspicious. Muons, rather like heavy electrons, don’t quite behave as the Standard Model might have us believe, hinting at fields and possibly particles or forces hitherto unknown. Dr. Harry Cliffe – a member of the LHCb team who found something similarly weird two weeks ago - describes the finding and the level of excitement amongst theorists worldwide.

Superfans around the world have learned to speak fluent Klingon, a fictional language originating from Star Trek. In a quest to understand the science behind these languages often dismissed as gobbledygook, Gaia Vince has been speaking to some of the linguists responsible for creating these languages. It’s time for her to relax the tongue, loosen those jaw muscles and wrap her head around the scientific building blocks embedded in language and what languages like Klingon tell us about prehistoric forms of communication.

Also, gossip often has negative connotations, but does it get a bad rap? Might it serve a useful function and should we think of gossiping as an advanced social skill rather than a personality defect? CrowdScience listener Jayogi thinks it might be useful, and has asked CrowdScience to dig into the reasons why we find it so hard to resist salacious stories.

Datshiane Navanayagam meets a scientist who views gossip as a key evolutionary adaption - as humans started to live in bigger cooperative groups, gossiping was a way of bonding and establishing acceptable group behaviour as well as cementing reputations of trustworthiness.

Datshiane heads to the local park to catch some real gossiping in action and finds out that whilst people like to gossip they don’t consider themselves gossipers.

Datshi asks a team of scientists what information we are most keen to share and glean in these interactions and if there is such a thing as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ gossip. She hears that in some group settings – like in the workplace - gossip can enhance cooperation and limit free-riders, but that it can also have a more self-serving dark side.

Datshiane finds out if our stone-age gossipy minds are fit to operate in the world of mass communication and social media – is our fixation on celebrities related to our being hard wired to gossip?

Image: Platelets, computer illustration. Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki /Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Last on

More episodes

Broadcasts

- Sat 10 Apr 2021 23:06GMT����ý World Service South Asia & East Asia only

- Sun 11 Apr 2021 00:06GMT����ý World Service except East Asia & South Asia

Podcast

-

![]()

Unexpected Elements

The news you know, the science you don't