Better Radio Experiences (BRE) was a six-month project about inventing novel audio experiences for young audiences. We recently published a blog post that shared a bit about our user-centred approach to the project and the lightweight prototypes we made as a result. The project is now complete and our methodology was a success. We think it’s worth sharing more details about what we did to make sure our experimental innovation project was user-centred.

We got off the ground fast

BRE was a short project and it was all about making lightweight, physical things (not digital things) and our approach to user research needed to support that. We needed to engage with our target audience fast and start making things as quickly as possible. We kept the research plan simple, aimed for good over perfect and - crucially - made sure the whole team engaged in the research process and got in front of users early on and throughout. Research was a team-wide effort.

In six weeks, we planned and completed a research project with eight creative young adults as participants. The research included a diary study, followed by one-on-one phone interviews and a co-design workshop. We completed the project with a prototype evaluation workshop with sixteen 15-year-olds.

The research process provided the opportunity for the whole team to observe and interact with users first-hand, and it generated a lot of useful data in the form of verbatims and narratives, user stories, and ideas co-created with participants. The results of the research formed not only the basis for all our ideation, prototyping and cross-departmental hackdays, but also insights for other ����ý teams to consider whilst working on audio-related projects.

- ����ý R&D - What Do Young People Want From a Radio Player?

- ����ý R&D - Prototyping, Hacking and Evaluating New Radio Experiences

We researched to the extreme end of users

We consciously biased our research towards the extreme end of our target audience. We wanted to work with 18 to 21 year olds who were creative and actively engaged in audio-related arts.

Our participants were opinionated, creative and not representative of the general public. This was amplified by the fact that (because of time constraints) we limited our research area to Bristol, where we had existing connections. We knew our bias and we were okay with that. Our aim wasn’t to create services or products that meet current user needs, but rather to gather true-to-life narratives that we could use to generate novel ideas—ideas that would help us challenge perceptions and open new possibilities for design. We used the narratives we collected to leapfrog off of, rather than respond directly to.

What was interesting is that, having completed the research, we reviewed previously completed research studies that engaged much larger and more representative cohorts; and discovered that many of our insights matched theirs. Though the narratives we gained in having done the research ourselves (and our care in keeping those narratives intact for ourselves) meant that we had a much richer view of learnings than if we’d read through a few reports.

And herein lies a big nut to crack for research teams: how can we store and share our research data so that it’s easy to scan and yet retains its richness? It's an interesting matter for consideration, but not one that we'll go into here.

The whole team owned the research

We were a small team of five people - a producer, a user researcher, two engineers and a designer. We all took part in planning, recruiting and analysing research, and we all spent at least six hours with users and many more engaging with the resultant narratives and insights.

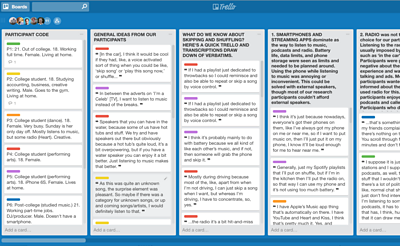

The team was primarily distributed, so we used Trello for affinity-sorting verbatims and observations and made sure that the whole team had access to the board. Although Trello is a relatively time-heavy way to do analysis, particularly for that amount of data, it paid off.

As everyone in the immediate team had engaged with the research participants, the verbatims served as a powerful reminder of what we’d learned and who we were innovating for.

Trello’s search feature allowed us to almost instantly develop new columns to see what verbatims and observations we had around themes we were discussing: skipping and shuffling, for instance. It also allowed us to search interview transcriptions and add relevant data to a new column with a simple copy and paste. This was useful in making sure that we weren’t making things up about our users - conflating or inflating our stories - and it allowed us to offer insights (as opposed to opinion) as to why an idea wasn’t grounded in user narrative. Because, although we were leapfrogging off user narratives to create new, unexpected things, we still wanted to make sure we kept a clear connection to the things we’d learned from users. It’s an interesting balance to play.

The Trello board was also a very useful resource during our hackday too. The hackday involved makers and engineers from across the organisation who’d not been involved in the research. With the board, we could quickly locate verbatims to illustrate a point and help makers more directly connect with what we knew about our users. We focused on shared narrative over ‘data’.

Synthesised research assets—things like verbatims and user stories—are really useful for distilling what you’ve learned during research into something more digestible. But they don’t bring the research to life.

In sharing the research, we found that focusing on the full narrative, over synthesised research assets, was a very powerful technique for keeping the users ‘alive’ in the team and bringing their stories to life for the various artists, makers and engineers who collaborated with us during the project. The art of storytelling, campfire-style, was integral to this. We gathered people around a wall of user stories - just 15 bits of paper tacked to a wall - and expressively unravelled the personal interactions and sharings behind each.

User stories and verbatim quotes aren’t emotive. They’re excellent triggers for recall, though, once the person being triggered shares the narrative. We used this concept in our hackday.

A triumph of a hackday

On the first morning of a hackday with makers and engineers from across the ����ý, we did a 20-minute ‘vertical campfire’, as alluded to above. Mental triggers set (in the form of narrative around user story), we included the user stories on sorting cards that were used as part of an ideation session. The results were remarkable.

It was clear throughout the hackday, and certainly during the final presentations, that everyone in the room was invested in and understood the user stories. They repeated them, reminded each other of them, and made prototypes for them. Things were made that really expressed what we’d learned about our users, and they were still things that were interesting and innovative. A moment of research triumph.

We took the prototypes that were made to a group of 15-year old technical students to explore how they might use them and make them better. Our favourite prototype was made in response to two stories that related to sound and nostalgia:

I want to listen to music that I listened to with a person, or from a holiday, festival or gig that I went to, so that I can vividly remember that time.

This approach to research wouldn't be appropriate to every project, but for a fast, lightweight project that was about shifting perceptions and exploring novel experiences, it worked a treat. It's also bestowed on us a much greater respect for the power of storytelling in research.

-

Internet Research and Future Services section

The Internet Research and Future Services section is an interdisciplinary team of researchers, technologists, designers, and data scientists who carry out original research to solve problems for the ����ý. ����ý focuses on the intersection of audience needs and public service values, with digital media and machine learning. We develop research insights, prototypes and systems using experimental approaches and emerging technologies.