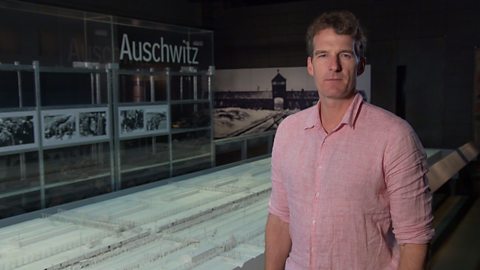

DAN SNOW: Hello, I'm Dan Snow, and I'm at the Holocaust exhibition in the Imperial War Museum finding out about the awful suffering of Europe's Jewish population during the Second World War.

DAN SNOW: It's well known, of course, that millions of Jews were murdered by the Nazis, but not all of them were automatically killed. Some were kept alive to work for the German military and managed to survive.

DAN SNOW: And here is one such tale, from the ǵüµÇ¨û§'s archives. The remarkable story of a woman called Anka.

NARRATOR: Anka had arrived at Auschwitz pregnant with Eva, and her life was in grave danger.

NARRATOR: The Nazis assessed all inmates and decided who would live and who would die.

ANKA BERGMAN: We went through these so-called selections where they picked people who were most capable of eventually doing some war work.

NARRATOR: Pregnant women were routinely sent straight to the gas chambers.

NARRATOR: But, for now, Anka's pregnancy would go undetected. She was selected to live.

ANKA BERGMAN: We were given some food and some better clothes and we were put on a train and sent away from Auschwitz. And that was just marvellous.

ANKA BERGMAN: The feeling that we were leaving Auschwitz alive, you just can't imagine. It was heaven.

NARRATOR: In October 1944, Anka was just three months into her pregnancy. If discovered, she would be sent straight back to Auschwitz to a certain death. But for now, the greatest threat to Anka and her unborn child was the lack of food and warmth.

ANKA BERGMAN: We were like sardines again in that train and there was only one bucket and it all started overflowing pretty quickly and no food and no water.

NARRATOR: Anka was on her way to an armaments factory.

ANKA BERGMAN: We went up a hill to a huge factory and it opened the door and it was warm there. And we saw and smelt the bed bugs. I don't know if you have ever seen one, but they are little beetles which wouldn't matter so much but they have that certain smell, sort of sweet. Never mind!

ANKA BERGMAN: I never smelt it since and I hope, I hope not to smell it again, but there were thousands of them and that meant warmth.

NARRATOR: Anka was to spend the next six months riveting the tail fin of the V1, the unmanned flying bomb, the notorious doodlebug. Compared to Auschwitz, the factory was a haven, but Anka's life was still at risk.

ANKA BERGMAN: I was getting thinner and thinner but my stomach was getting bigger and bigger.

NARRATOR: Discovery of her condition would have meant her immediate return to the gas chambers.

ANKA BERGMAN: I perhaps am the only person, idiotic as I am, who thought that I would get through it and I will come home, never doubted it.

ANKA BERGMAN: And seeing all these people going in the gas every day and every day and so on and so on and being pregnant and the baby, I knew I was coming home, which is totally stupid. But I lived with this idea.

NARRATOR: By the February of 1945, Anka was seven months pregnant and was now in great danger of being discovered by the Nazis. Miraculously, she would be spared the fate of the gas chambers. At the end of the January, Auschwitz had been liberated by the Russians.

NARRATOR: But there was now a new threat to Anka's life. The Nazis had started to evacuate the camps and factories to annihilate all living witnesses to the Holocaust.

NARRATOR: Anka was put on yet another torturous train journey, heading south away from the advancing allies.

ANKA BERGMAN: There was no food and no water and no nothing, and we were in open coal wagons.

NARRATOR: The train journey lasted three weeks, and during this time many people lost their lives to hunger.

NARRATOR: Anka was on the brink of starvation and by now was nine months pregnant. Finally the train arrived at its destinationãÎ Mauthausen Death Camp.

NARRATOR: At this very moment, Anka went into labour.

EVA CLARKE: When my mother saw the name "Mauthausen" at the station she was very shocked because as opposed to when she'd arrived in Auschwitz not knowing what that was, this time she knew because she had heard about this appalling place from very early on in the war.

EVA CLARKE: And she says the shock was so great that she thinks it provoked the onset of her labour and she started to give birth to me on that coal truck.

ANKA BERGMAN: We went up the hill and I was sort of starting to give birth to the child and there they stopped just before the opening of the main doors of Mauthausen, and then I had to climb down from that wagon and nobody helped me. There was this Russian doctor who was with us and who you knew slightly, the prisoner. And she was just passing. I begged her to help me and she turned round and went. I mean, a doctor.

ANKA BERGMAN: The baby came out and we were still going for about ten minutes, I think, and then they called a doctor from the camp, the prisoner, and he was a gynaecologist by pure fluke and he cut the baby off and smacked its bottom and it was a healthy baby and I was in heaven.

ANKA BERGMAN: Her arms were like my little finger. I mean, she was tiny. You didn't dare to touch her.

EVA CLARKE: They think I weighed about three pounds. I was wrapped in paper. My mother just held me all the time.

NARRATOR: Despite all the odds, Anka's baby had made it into the world but at the worst possible moment.

NARRATOR: The Nazis were desperately getting rid of all witnesses to their crimes. In the dying days of the war, thousands were shot, gassed and starved to death.

NARRATOR: Anka and her new-born baby were on their way to the gas chambers of Mauthausen. But then, another miracle.

ANKA BERGMAN: The Germans disappeared.

ANKA BERGMAN: Nobody threw them out, no-one, suddenly they were gone.

EVA CLARKE: There are two reasons why we survived, and the first is that on the 28th April, 1945, the Nazis had dismantled the gas chamber in Mauthausen. Well, my birthday is the 29th.

EVA CLARKE: So presumably had my mother arrived on the 26th or 27th, again, I wouldn't be sitting here today. The second reason we survived was because a few days after my birth the American army liberated the camp. My mother reckons she wouldn't have lasted much longer.

NARRATOR: Anka's four years of Nazi imprisonment were finally over.

NARRATOR: When she was strong enough she and baby Eva returned home to Prague.

NARRATOR: Anka was free at last, but she and Eva were now alone in the world.

ANKA BERGMAN: That was the worst moment of the whole war for me, to arrive in Prague which I wished all through the time, "When will I be home?" And there was no home.

ANKA BERGMAN: I come from a big family and there was nobody, nothing. I didn't know where my next meal will come from because I had no money, no clothes and a little baby.

EVA CLARKE: But nevertheless she still had a vestige of optimism in the back of her mind, and she asked somebody to give her some money to go on the tram. And she thought that if anybody had survived, there was a chance it would be her cousin.

ANKA BERGMAN: I ring the bell and the door opens and the whole family waits for me there and say, "Where have you been? We heard you are coming to us." And they were just marvellous. Now I'm going to start to cry.

ANKA BERGMAN: I can'tãÎ

ANKA BERGMAN: Well, I asked them if I could stay a few days and they said, "Of course." And a few days ran to three and a half years and it was just, I found a new family.

DAN SNOW: So, as we've seen, once the war was over the Jewish survivors had to deal with the fact that all their families, friends, often everyone they knew, had been killed. Anka found a surviving relative which made her one of the very few lucky ones.

Video summary

Pregnant women were normally sent straight to the gas chambers, but Anka survived the selection process and was transported in October 1944, whilst 3 months pregnant, on a cramped train to an armamentãs factory in Germany.

Her job was to help with the construction of a V1 ãDoodlebug.ã

The Nazis started to evacuate camps to cover up evidence of what had happened during the Holocaust.

When 7 months pregnant, Anka was sent on a 3 week train journey to Mauthausen death camp. Anka gave birth at the camp in April 1945.

Nazis dismantled the gas chambers at Mauthausen to try and hide what had happened there.

Shortly after Anka gave birth to Eva, the US army arrived and liberated the camp.

Anka found it difficult to return to her home in Prague with her baby as many of her family members had been killed in the Holocaust.

She relied on the help of her cousin and extended family for support.

This short film is from the ǵüµÇ¨û§ series, World War Two with Dan Snow.

This short film contains scenes which viewers may find upsetting. The films are intended for classroom use but teacher review is recommended prior to watching with your pupils. You know best the limit of your pupils, and ǵüµÇ¨û§ Teach does not accept any responsibility for pupil distress.

Teacher Notes

Students could look at this short film to consider the legacy of the Holocaust.

How might survivors feel after camps were liberated and the war came to an end?

What challenges faced survivors when they returned home? This is an important aspect of the Holocaust - what help and support would survivors need, and where could they get help from?

This could include a discussion about the roles of other countries and organisations.

This short film will be relevant for teaching KS3 and KS4/GCSE history in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and National 4/5 history in Scotland.

What does Rudolph HûÑss' evidence tell us about Auschwitz? video

Dan Snow introduces a report about the role of Rudolph HûÑss, the commandant of Auschwitz, in the Holocaust, based on the testimony he wrote before his trial.

What were conditions like at Auschwitz? video

Dan Snow introduces a clip about the brutal conditions faced by people at Auschwitz, including testimony from a survivor.

How did Auschwitz expand? video

Dan Snow introduces a clip about the expansion of Auschwitz to deal with the number of Jewish people being transported to concentration camps.

How did the use of gas chambers develop in the Holocaust? video

A look at the introduction of gas chambers at Auschwitz, how the Nazis started using gas vans and then going on to use gas chambers at camps.

What happened in the gas chambers at Auschwitz? video

A report about the gas chambers at Auschwitz, including some of the testimony from Rudolph HûÑss.