D-Day weather: Was this the most crucial forecast in history?

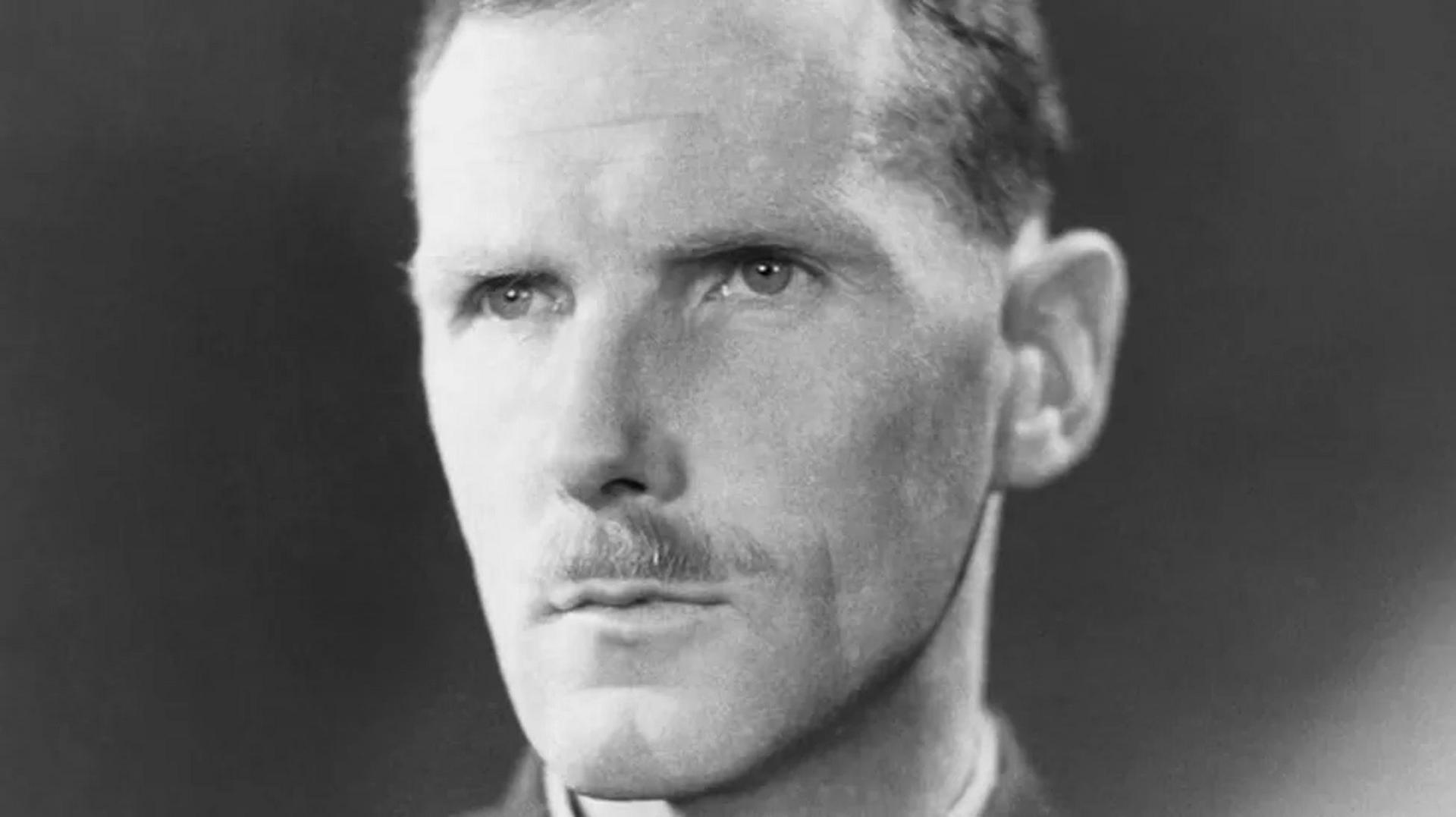

As chief meteorological adviser, Group Captain James Stagg was the man under pressure to get the forecast right

At a glance

Weather forecast crucial to the success of D-Day

Forecasting ability much more limited in 1944

Course of the war changed thanks to the expectation of a brief improvement in weather conditions

- Published

Every day we all make split decisions related to the weather. Will I need an umbrella? Is it going to be sunnier at the coast?

As a weather forecaster I'm acutely aware of the responsibility in guiding those decisions every time I am on air, even if the forecast isnÔÇÖt completely clear cut.

In those situations phrases such as ÔÇ£high probabilityÔÇØ, ÔÇ£risk ofÔÇØ and ÔÇ£80% chance ofÔÇØ are used to put you in control of making the right decision for you.

In most cases, if it turns out to be a wrong decision the impacts are, thankfully, small.

Now imagine if the safety of 160,000 troops, 13,000 aircraft, 5,000 ships and the course of a world war relied on that forecast. The pressure to get the forecast right, or at least offer the correct guidance, would have been immense.

The pressure to get the forecast right

Group Captain James Stagg was the man under that pressure, 80 years ago in the lead up to the D-Day invasion - the start of the Allied efforts to liberate France and western Europe.

As Chief Meteorologist at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expedition Force, it was his job to inform General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, of weather conditions that would make or break an invasion on the north France coast.

Synoptic weather chart showing conditions on D-Day

The expectant weather was the crucial last piece to a jigsaw of conditions required to be met for an invasion to take place.

A full moon, giving good visibility and night-time illumination, as well as low tides to allow safe arrival on the Normandy beaches were the first parts of the puzzle.

With a full moon and low tides expected on 5, 6 and 7 June, the pressure was then on the delivery of a favourable weather forecast.

Even now in a world of computer modelling, satellite, radar data and widespread observations, that can be a tough task some of the time, but in 1944 to even forecast 24 hours ahead was incredibly difficult, let alone forecasting conditions several days ahead.

Finding a 'window of opportunity'

Group Captain Stagg and the three separate teams of meteorologists (two British and one American) mainly relied on a limited set of observations across Europe, the north Atlantic and eastern US to draw up weather charts and predict the weather's progress.

By the end of May 1944 general weather conditions across the UK and north-west Europe had become rather disturbed, with wet and windy areas of low pressure becoming more dominant.

General Eisenhower was in charge of the decision to invade or not

General EisenhowerÔÇÖs initial plan to invade on 5 June was stopped by Stagg, as a potent area of low pressure was forecast to cross the UK, bringing strong winds and extensive low cloud to the English Channel.

However, as the weather charts were being drawn up on 4 June, a late weather observation from a ship in the Atlantic identified the potential of a brief ridge of high pressure building after the passage of the low. This, Stagg believed, would be enough to provide a ÔÇ£window of opportunityÔÇØ for the invasion to take place on the 6th instead.

Weather briefings early on 5 June remained optimistic, even if conditions were still considered marginal.

Were they to delay the invasion until the next low tide the Germans may have spotted the build up of forces along the coast in England and anticipated the invasion.

Landing craft gather by a Normandy beach on D-Day

On the other side of the Channel, we now know that the Germans had a better idea of the weather situation in the Atlantic than the Allies initially thought.

It is believed they had managed to crack some of the Americans' encrypted weather observations, allowing them to draw up fairly accurate weather charts.

From these, their team of meteorologists made the judgement that conditions would not be good enough for an invasion.

German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel even left his position in France and returned to Germany to give his wife a birthday present on the strength of that forecast.

Allied troops prepare to leave their landing craft to invade Cherbourg in Normandy

Changing the course of the war

The invasion went ahead as planned. A brief weather window had indeed opened, but conditions were far from ideal and slightly worse than expected.

Low cloud sat over parts of the north France coast, limiting visibility of the ground to aircraft overhead. Winds were also stronger, making seas rougher and the tide higher. The Channel crossing became vomit-inducing and energy-sapping for many troops. This all made landing on the coast far more challenging than had been anticipated.

However, the risk of taking the decision to invade in such marginal conditions paid off. The Germans were taken by surprise, and the course of the war changed. Had a decision been made to delay two weeks until the next ideal window, any invasion would have been prevented by the stormiest weather to hit the Channel in 20 years.

Even though the weather forecast given on the 4 and 5 June 1944 wasnÔÇÖt completely right, the use of probability and the meteorological advice given ultimately helped shorten the war and save thousands more lives.

Eight decades later, and despite the advance in technology, weather forecasting is still based on the balance of probabilities, due to the chaotic nature of our atmosphere. Thankfully though, for most of the time the main decisions we make based on that advice are based around what we wear and what trips we make.

- Published21 April

- Published5 June 2019