Esther Chan is First Draft's Australia Bureau Editor. aims to empower people with knowledge and tools to build resilience against harmful, false, and misleading information.

Political propaganda has a well-documented influence on voters in and alike. Through hero-worshipping, identifying common enemies, launching smear campaigns and repeated messaging to reinforce ideologies, propaganda is extremely powerful in its ability to capture voters’ imaginations and feed on their fears. Since the founding of First Draft in 2015, we have witnessed how that power, when used to , has been magnified by the machinery of social media platforms and messaging apps.

The 2020 US election is a valuable lesson on what shapes and sizes disinformation campaigns can appear, where they take place online, and how — when enough momentum is gathered — they spill into real life. Our global team of researchers monitored online narratives and sentiment around the clock. how disinformation regarding Dominion Voting Systems machines allegedly being tampered with traveled far and wide on mainstream social platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, as well as semi-closed spaces like Telegram and the now-defunct forum The Donald. The forum, frequented by supporters of then-President Donald Trump, was one of the key conduits alongside other platforms, including the fringe message boards 4chan and 8kun, . The cross-platform communication turned into a real-world riot, symbolic of the challenge to US democracy.

Common types of election disinformation

Election disinformation is not bound by geographical constraints and can inspire similar actions that undermine electoral integrity thousands of miles away — often without any . Unproven claims about the purported involvement of Dominion’s voting machines in elections have traversed international borders and been repurposed to suit the narrative that foreign forces were behind the February 2021 Myanmar coup and to sow scepticism ahead of the Australian election, held by May.

In the lead up to the Australian election, First Draft researchers have found that various types of election-related disinformation circulating online prior to the US election have taken on a new life in Australia, via local private Facebook groups and semi-closed Telegram channels. These include:

- Disinformation about election infrastructure, process, voting procedure (vote counting, voting locations/dates), candidates and polls, with allusions to foreign interference.

- Disinformation targeting communities based on nationality, religion, language, sexual orientation or gender identity, such as the targeting of the , and in Australia, disinformation against the community, evident ahead of the 2019 election. have also become a clear target, . The strained relations between China and the West are exacerbated by the that the coronavirus is a bioweapon created in a Chinese lab.

- Disinformation on other pressing issues, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the vaccine, as well as the climate crisis, is appropriated in efforts to undermine the government or the integrity of the election. Our research has shown that some anti-vaccine activists have adopted extremist narratives, such as Nazi references as seen in , , . Anti-establishment sentiment, whether rooted in discontent towards how governments have handled the pandemic or nationalistic ideals, can and work toward the common goal of disrupting elections.

Tactics and techniques

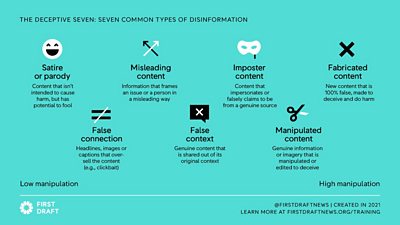

First Draft created a framework in 2017 for a more nuanced understanding of the used to spread false or misleading information — namely, the . From a scale measuring the intent to deceive, they are: satire or parody, false connection, misleading content, false context, imposter content, and manipulated and fabricated content.

These tactics can be deployed, often by individual users, via text, and including memes, GIFs, images, and videos. The level of skill required to create these types of content also varies. Out-of-context misinformation can sometimes be traced back to of the original content. Meanwhile, shallowfakes are easily manufactured, for instance by altering the speed of a video. are on the other end of the spectrum in terms of technological requirements, involving the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence to create synthetic and manipulated content.

Strategies, online platforms and closed spaces

These tactics and techniques form the basis of the key strategies to disseminate and promote mis- and disinformation, sometimes in collective or coordinated efforts in the form of . A few strategies detailed in the include astroturfing, brigading and keyword squatting. Astroturfing is an organized effort to hide the source of information or manipulate engagement statistics to create the impression that the issue has more support than it actually does. includes different types of coordinated behaviours, including the use of fake accounts, to steer the conversation. Keyword squatting is the domination of a keyword, phrase or hashtag by populating it with content in favour of one’s goals. is an example of how the nature of an agreeable slogan was fundamentally changed to facilitate conspiracy theories about an international child-trafficking ring.

The strategies and tactics involved are sometimes difficult to detect and decipher because of the opaqueness of the platforms and mobile apps where they appear. As a result, disinformation about elections flows through semi-closed and closed spaces as well as fringe platforms, often undetected. In Australia, Telegram has proven popular among anti-vaccine and anti-lockdown groups. Public channels on the chat app are theoretically open to all but are not always easy to find. In favor of less scrutiny compared with mainstream social media platforms, politicians such as are increasingly moving their campaigning and crafting their messages for users in semi-closed and closed spaces.

Underexplored nooks and corners of the internet have also proven to be a hotbed of disinformation, including , and false claims promoted under the guise of . Adding to the challenge, as First Draft pointed out , is that culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities have different social media habits, such as using WeChat and Weibo in the Chinese diaspora, in Japan and in South Korea.

First Draft notes that:

the closed or semi-closed nature of these spaces makes it difficult for journalists and researchers to obtain a complete picture of the volume and flow of misinformation. Crucially, the labels applied to misinformation in ‘open’ spaces such as Twitter and Facebook do not always travel with the false or misleading posts when they are shared on other platforms. Rather, inaccurate information circulates unchecked across the diaspora once it leaves the platforms where the contextual warnings were applied.

More from the Trusted News Initiative

- First Draft Part Two: Prebunking and avoiding amplificationIn the second of a two part blog on disinformation and elections from First Draft, Esther Chan writes about how journalists can responsibly cover the problem.

- Voting for truth: the challenge for democracyJournalists from around the world tell the Trust in News 2022 conference how they hold power to account.

- Five ways journalists can combat misinformationTop tips from the ����ý's Rebecca Skippage on getting good quality information to our audiences.