Introduction to cholera

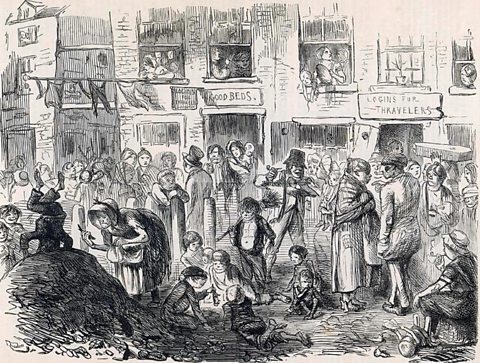

Access to clean water and good sanitation is crucial to staying healthy and well. The fact that contaminated water and poor sanitation could help spread diseases like cholera was not understood in the 19th century.

Starting in 1819, a series of cholera pandemics spread the disease from the Ganges in India to the rest of the world, killing millions of people. In 1854, 23,000 died from the disease in the UK.

It took some brilliant detective work and some very expensive public health problems to rid the nations of the disease.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCholera's first appearance, 1831

Image source, ALAMY

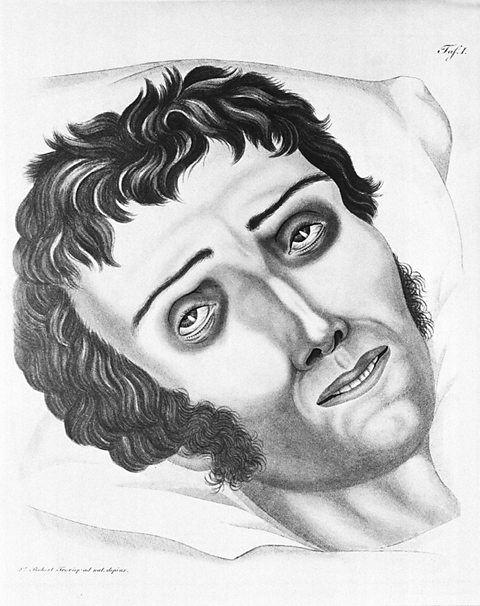

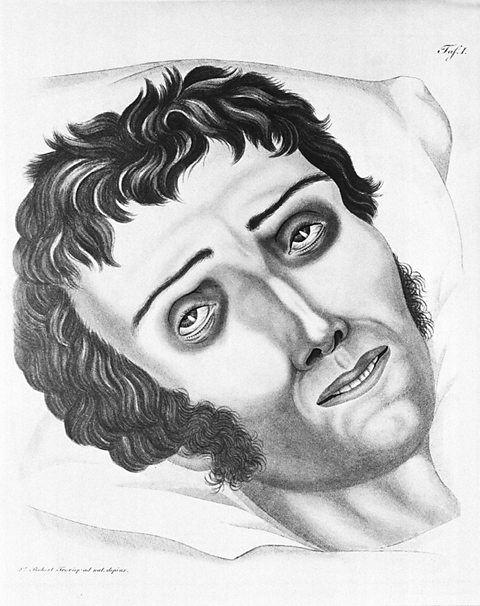

Image source, ALAMYcholeraA waterborne disease which causes severe diarrhoea, dehydration, lethargy and erratic heartbeat. It can be fatal within hours of infection. first struck Britain in 1831 during the second pandemic of the 1800s.

It was often described as вҖҳinvadingвҖҷ the country and it caused fear and panic in communities that experienced outbreaks.

As the disease was new to Europe, the medical profession in Britain had no idea how the disease spread or how to treat or cure it.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYBeliefs about cholera

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYAt the time there was no understanding of bacteria and infection. It was initially assumed that cholera was called by foul smells and bad air.

After choleraвҖҷs first appearance in Britain, the lawyer and social reformer, Edwin Chadwick, was appointed to carry out an enquiry into sanitation in Britain.

He believed that by cleaning the streets, by removing human waste, the health of the population would improve.

This belief was based on the theories of miasmaBad air, smells or odours. Many people in medieval times believed it spread disease.. Chadwick believed that by removing human waste, bad smells would also leave and disease would stop being spread.

In London, this plan led to more waste and sewage flowing into the River Thames. This increased the occurrences of cholera outbreaks, as the Thames was the main source of drinking water for the city.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCholera and contaminated water

In 1848, there was a second outbreak of cholera in London.

Dr John Snow, a physician and specialist in medical hygiene, doubted that bad air caused the disease. Dr Snow carried out his own investigations and published his findings in a paper entitled On the Mode of Communication of Cholera in 1849.

In this paper he theorised that cholera was not transmitted by bad air but through tainted water supplies.

Dr Snow's cholera map, 1854

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn 1854, during the third cholera outbreak in London, Snow set out to prove his theory that unclean water caused the spread of cholera.

He used a map to plot where cholera deaths had taken place in the area around his medical practice. The map showed a concentration of deaths in one area and Snow was able to trace the source of the outbreak back to a contaminated water pump in Broad Street in the Soho area of London.

Snow removed the handle of the pump, making it unusable, and the number of deaths declined rapidly, however by this time the epidemic had passed its peak.

It was later discovered that the drinking water supply had been polluted by a leaking cesspitAn underground tank or pit used to collect waste water and sewage.. Snow had proved that unclean water led to cholera.

Despite having statistical evidence to prove his theory on the origin of cholera, SnowвҖҷs findings were not embraced by the medical profession at large.

In 1854, the General Board of Health acted on SnowвҖҷs information about the polluted water supply but they refused to accept Snow's claim that cholera was spread through water.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCholera and sanitation

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYIn the summer of 1858, the combination of sewage in the Thames and high temperatures resulted in an awful stench - it was so bad that it was referred to as the Great Stink.

Parliament, still holding fast to the theory of the role miasma played in spreading disease, were convinced that something had to be done.

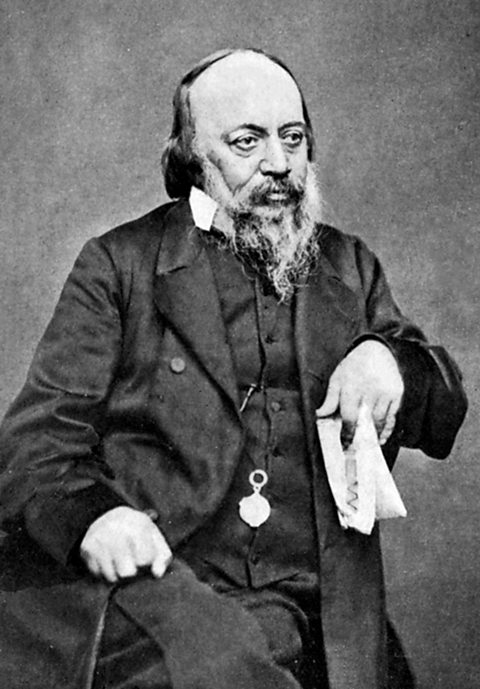

An engineer called Joseph Bazalgette was given the task of creating a new sewage system for London. The project brought numerous health benefits to the people of London.

It also helped prove the link between polluted water and cholera.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYLondon's sewers

Image source, ALAMY

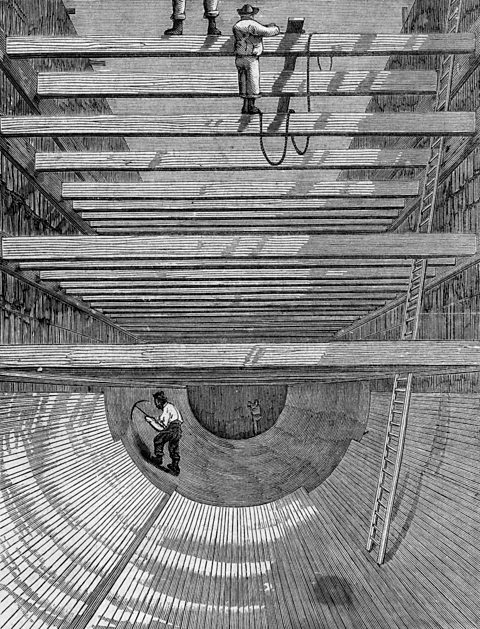

Image source, ALAMYBazalgetteвҖҷs system was designed so that, instead of sewage flowing into the Thames in London, it would be carried through brick walled sewer tunnels to the tidal basin of the River Thames - where it could be swept out to sea.

The new sewerage system was opened in 1865 however not all of London had been connected by this point and cholera hit London again in 1866.

This time the outbreak was centred on areas in the east of the city which had not been connected to the new system. The residents of this area were still forced to drink contaminated water from the Old Ford Reservoir.

The isolated nature of this outbreak was further proof of SnowвҖҷs theories regarding the causes and spread of cholera. Those who had previously doubted him, including the General Board of Health, accepted his findings that cholera was a waterborne disease.

The east of the city was connected to the main sewerage system some time after and there were no more significant outbreaks of cholera in the UK.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCholera and Glasgow's water supply

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYScotland did not escape the horrors of cholera.

Glasgow, then an overcrowded industrial city, experienced several cholera outbreaks. The first outbreak, in 1832, killed around 3,000 people in the city. Another outbreak in 1848 killed almost 4,000 people.

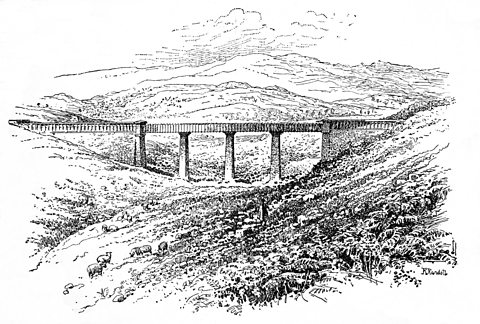

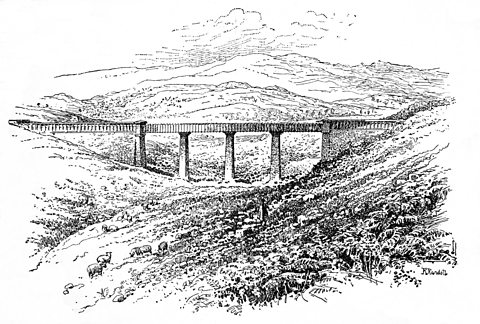

After another outbreak in the city, in 1855 action was taken to improve the city's sanitation and water supply. Loch Katrine in the Trossachs was dammed, and an aqueduct and tunnels built to transfer fresh water to the city. The scheme cost ВЈ468,000, a huge amount at the time, and took four years to complete.

The money proved well spent and, together with improvements in the city's sewers, the fresh water supply helped eradicate cholera outbreaks in the city.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Medicine through time

Find out more by working through a topic

- count6 of 8

- count7 of 8

- count8 of 8

- count1 of 8