Ever since the ����ý Empire Service was launched towards the end of 1932, listeners in the Caribbean equipped with short-wave receivers would have been able to hear British radio programmes. At first, however, their only option would have been to eavesdrop, whenever atmospheric conditions allowed, on signals from the Corporation’s Daventry transmitter intended for English-speakers in West Africa or India.

It was the Second World War which created a clearer strategic need for programmes specially-made for the region. Just as in the First World War, many thousands of men and women from across the West Indies were now joining-up to fight for the Allied cause. Many were stationed in Britain, some four thousand miles from home. Others would be needed to replace factory-workers, and a recruitment campaign began in Jamaica and elsewhere.

Since the ����ý had long conceived of international broadcasting as a means of providing a vital bridge between the centre of a sprawling Empire and Britain’s various overseas colonies, it was only natural for it now to provide a forum in which serving men and women from the islands could send messages to their friends and families back home.

In 1943, equipped with new transmitters and extra staff, the Corporation began regular transmission of its series, Calling the West Indies. The programme’s characteristic mixture of personal messages, warming music, and uplifting tales of dedicated war-work was featured in a 1944 cinema newsreel, West Indies Calling:

The newsreel shows a young radio producer acting as compere. It is a rare glimpse of one of the ����ý’s true pioneers, the first black producer on its payroll, Una Marson.

Marson, originally from Jamaica, was already an experienced journalist and published writer by the time she started working at the ����ý in 1939. Her first role in the Corporation was working with Cecil Madden and Joan Gilbert at the Alexandra Palace television studios. When the outbreak of war meant the sudden closedown of the ����ý’s TV service, she transferred to radio, working both behind-the-scenes and on-air. In this rather fragile recording from 1940, we hear her interviewing the jazz-band leader Ken "Snakehips" Johnson, just a matter of months before he was killed by a bomb in the London Blitz.

Marson joined the ����ý full-time in March 1941, when she became a Programme Assistant in the "Empire Programmes" department. By this time, not only had she been vetted by the security services as internal documents reveal, the ����ý had also apparently seen fit to "check with the Colonial Office that there would be no objection on their part to our appointment of a coloured British subject".

Her interest in poetry soon led her to develop Caribbean Voices, a weekly feature within the Calling the West Indies series, which started towards the end of the War. It included poems and short stories by Caribbean authors, many of whom were either completely unknown or only just beginning to establish an international reputation.

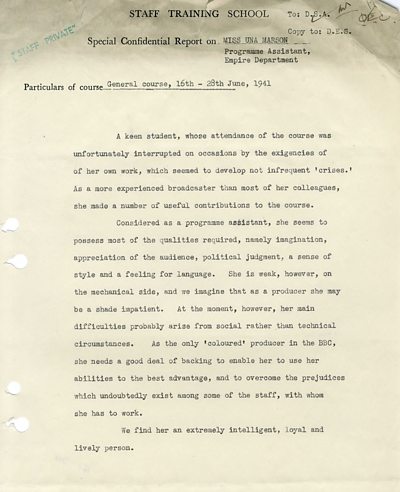

This pioneering role with Caribbean Voices was tragically short-lived. Marson’s managers wrote privately of her being an "excellent producer". But she was clearly overworked. And there is troubling evidence that she had to deal constantly with niggling racial intolerance from colleagues. A confidential report on her performance during a ����ý training course, though generally positive, wrote of the "social" difficulties she faced due to "the prejudices which undoubtedly exist among some of the staff".

"A keen student, whose attendance of the course was unfortunately interrupted on occasion by the exigencies of her own work, which seemed to develop not infrequent 'crises.' As a more experienced broadcaster than most of her colleagues she made a number of useful contributions to the course.

Considered as a programme assistant, she seems to possess most of the qualities required, namely imagination, appreciation of the audience, political judgement, and sense of style and a feeling for language. She is weak, however, on the mechanical side, and we imagine that as a producer she may be a shade impatient. At the moment, however, her main difficulties probably arise from social rather than technical circumstances. As the only 'coloured' producer in the ����ý, she needs a good deal of backing to enable her to use her abilities to the best advantage, and to overcome the prejudices which undoubtedly exist among some of the staff, with whom she has to work.

We find her an extremely intelligent, loyal and lively person."

Only a month earlier, Marson’s ����ý colleague, Joan Gilbert, who had worked on the famous pre-War TV programme Picture Page, had written to her bosses, claiming that Marson "seems to have got an exaggerated idea of her own position and her own authority". "Quite frankly", she added, "I wouldn’t let anybody speak to me in the way Una does, and certainly not a coloured woman".

By the end of 1945, Marson was apparently exhausted and wanting to travel to Jamaica for some badly needed rest. But her state of mind was deteriorating fast, taking matters out of her control. Within months she was in hospital, being treated, apparently, for "delusions" of persecution. By May 1946 she had been certified as suffering from schizophrenia and detained. The ����ý, which had granted her an exceptional period of sick leave, decided to assist her passage back to Jamaica, so that she could benefit from what one manager called "her home environment".

In October, she was driven to Swansea and put on the SS Tetela bound for Kingston, never to work for the Corporation again. Ten years later, Marson wrote to one of her old bosses, Laurence Gilliam. "My years at the ����ý", she told him, "now seem like a dream - an exciting dream which ended in a nightmare".

Responsibility for running Caribbean Voices henceforth fell to a young Irishman, Henry Swanzy. Between 1946 and the programme’s demise in 1958, it was Swanzy who established the series as an influential home for Caribbean literature and a vital source of patronage for its writers.

One of those whose work appeared on air at a crucial early stage was the Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott. In 2009, the ����ý producer Colin Grant interviewed him in his studio by the sea at St Lucia, and asked him about his first encounters with Caribbean Voices.

Swanzy started out with little direct knowledge of West Indian writing. Although he turned out to be an astute editor, he depended on a Jamaican couple, Gladys and Cedric Lindo, to make an initial selection from any written submissions and then send on to London any deemed suitable for broadcast. His real contribution, perhaps, was to help provide an amenable environment for the many writers who had come to London to try to make a living from their craft.

He would welcome them to the ����ý studios and all the ����ý watering-holes, host regular social evenings at his Hampstead home, and set them up with valuable contacts in London’s arts scene. Given the ����ý’s status as an arbiter of taste, paying them for their writing helped confirm the value of their work.

But Swanzy, acutely aware of their financial struggles, would also supplement their earnings by booking them as on-air readers for the series. As James Procter shows elsewhere on this site, the combined effect of this patronage was the rise of a whole new literary scene, linking London and the Caribbean, as well as the creation of a virtual community of listeners across the West Indies.

Actual recordings of the programmes have not survived. But the two programme scripts below, now held in the ����ý’s own written archives, give some sense of what these listeners would have heard. The first, from 27 April 1947, consists of comments on previous programmes. Henry Swanzy introduces the programme and his three guests: John Figueroa, Gordon Bell, and Ulric Cross. The second is an extract from an episode broadcast on 29 June 1947. It includes Samuel Selvon’s first appearance, through his poem Lucky Lucre:

After Selvon’s poem, the script shows Henry Swanzy closing the programme with a comment that "we haven’t seen many poems on animals". It was the kind of remark from Swanzy that showed how he would occasionally shape the content of subsequent programmes by gently directing listeners in the West Indies towards submitting work on themes that interested him or he thought might bear fruit.

Resident in London, white, Irish. On the surface, Swanzy was an unlikely champion of West Indian literature. Yet, in a 1998 Radio 4 programme in which Philip Nanton explored Swanzy’s life and work, we hear from among others, John Figueroa, George Lamming and Anne Walmsley; three writers who told Nanton that the success of Caribbean Voices almost certainly owed something to Swanzy’s Irish background, and the empathy this aroused in him for all colonised people:

Yet the problem remained. How appropriate was it for this one individual to have such extraordinary influence over a culture that was not his own - and for the ����ý in Britain to be the arbiter of Caribbean literary culture? It was a question Philip Nanton put in the same documentary to George Lamming and the Trinidadian literary scholar, Professor Rhonda Cobham-Sander:

At the time, there were also grumbles of a very different kind from inside the ����ý about both Caribbean Voices and other programmes still operating under the umbrella title of Calling the West Indies. Documents kept in the ����ý’s written archive reveal an unnamed staff announcer muttering in 1952 about hearing an unscripted on-air discussion full of "long hesitations, repetitions and fluffs", as well as speakers who were "impossible to understand". His pomposity provoked the ����ý’s Head of the "Colonial Service", John Grenfell Williams, into a blistering defence of the output. "The hesitations", he argued, "were those of two people, not fumbling for words, but feeling their way carefully and with a lot of thought". Programmes to the Caribbean, it would appear, didn’t only nurture a lively West Indian literary scene: they also showed the ����ý a way forwards to the looser, more spontaneous style of radio which would be more widely adopted a decade or more later.

Caribbean Voices ended in 1958. And the ����ý’s Caribbean Service which produced it was closed in the 1970s. When the Service re-opened again in the late-1980s, it based its output less on the literary heritage of Caribbean Voices and more on the strictly informational output which had always been heard in other parts of the Calling the West Indies strand. Programmes included a daily 15-minute news programme, Caribbean Report, and a weekly round-up, Caribbean Magazine.

During this long, uncertain period, countless interviews and reports were made by, among others, the freelance journalist Mike Phillips. In a recent interview, Phillips described how, when he first worked there, he found a series in need of fresh thinking, and, to his mind, a more politically relevant agenda - something that he and his new producer, Peter Lee Wright, urged in their dealings with senior ����ý management.

Phillips stopped working for the ����ý in the 1980s, and is now best-known as a writer of crime fiction - although in 1998 he published a book about the Empire Windrush, adapted into a ����ý TV series that same year. The book, and the TV series, helped revive historical interest in the "Windrush generation".

The ����ý’s Caribbean Service had a revival of sorts, too. As Phillips suggested, it developed a greater sense of urgency and topicality. Through the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st Century, it expanded its reach through developing a network of 50 partner radio stations in the Caribbean and the US.

In 2010, after the devastating earthquake in Haiti, it ran a month-long news service in Creole. The very next year, however, large-scale spending cuts meant it had to shut-down completely, along with several other language services that had been broadcast from Bush House for several decades.

Further Reading

- Glyne Griffith, The ����ý and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943-1958 (2016).

- James Procter, Writing Black Britain 1948-1998: An Interdisciplinary Anthology (2000).

- Clair Wills, Lovers and Strangers: An Immigrant History of Post-War Britain (2018).

London Calling: the ����ý and Caribbean Literature

-

London Calling: the ����ý and Caribbean Literature

The steady chimes of Big Ben that announced London Calling were regarded as the 'herald' of the Empire Service, a resounding echo from London’s imperial heart of unity and connectivity across a world falling apart. In the Christmas day broadcast below, the announcer urges listeners to 'girdle the earth with us' through the shared bonds of friendship, world harmony and the shrinking distances of global communication.

Related links

-

The former ����ý Caribbean radio service

-

Caribbean Voices Lenny Henry tells the story of Caribbean migration as reflected on stage and screen, from the 1930s, through the Windrush generation, to the end of the 1960s. From November 2015.

-

Caribbean Food Made Easy Caribbean cookery series in which passionate food enthusiast Levi Roots travels around Jamaica and across the UK showing how to bring sunshine flavours to your kitchen.

-

Women's History Network