Decades before the 'Raj revival' captured the attention of viewers and listeners - with Radio 4’s Plain Tales from the Raj, ITV’s The Jewel in the Crown and David Lean’s big-screen adaptation of A Passage to India - the ����ý embarked on a very literary relationship with India, one rooted in World War Two.

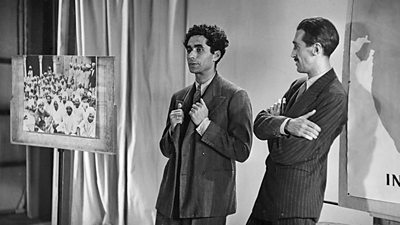

During the Second World War, the ����ý "Indian Section" came to be one of the Corporation’s most creative and collaborative units. Headed by two culturally and intellectually well-connected men - the civil servant Sir Malcolm Darling and the Indian broadcaster Z.A. Bokhari - the Section brought together a strong literary-infused team of writers and producers.

These included George Orwell, who had been born in India and worked as a policeman in Burma (inspiring his 1934 novel Burmese Days), and E.M. Forster, whose name had become popularly associated with the subcontinent since the success of his 1924 novel A Passage to India.

For writers such as Forster and Orwell, the compulsion to broadcast to India was driven in part by the need to win the propaganda war against German broadcasts popularised by the nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose. But they also welcomed the chance to address university students and opinion formers through radio talks on books and culture.

India’s freedom campaign was gaining pace and it that chimed with their own anti-imperialist sentiments.

Drawing on literary and personal contacts, the Indian Section team collaborated with a number of South Asian writers based in London at the time such as M.J. Tambimuttu and Mulk Raj Anand.

Through the ����ý, Indian and British socialised, attended literary events together, and published work in each other’s journals.

Changes took place more slowly in terms of India’s portrayal on the ����ý’s home networks. In 1947, the poet, Louis MacNeice, a star employee of the Features Department and friends with many of the Indian Section team, was asked to travel to India, to gather material for a series capturing the country’s momentous independence and the first, pivotal moment in the dismantling of Britain’s empire.

As August drew to a close, MacNeice set off from Delhi towards Punjab where he witnessed first-hand the communal violence of Partition and saw, as he wrote home to his wife, people ‘with their hands cut off’ and smothered by "hordes of flies". Partition’s horrors prompted MacNeice to write to Laurence Gilliam, the Head of Features Department, with an impassioned plea for the ����ý to rethink its proposed coverage and to tone down celebrations of the Raj’s legacy to avoid connotations of gloating and back-slapping.

Senior ����ý staff were concerned, but Gilliam eventually gave his consent for the series to be revised.

MacNeice’s programmes, made and broadcast in 1948, included two Home Service features - Portrait of Delhi and The Road to Independence - and his Third Programme opener India at First Sight. They were marked by a strong sense of self-awareness and discomfort about the British in India.

In Portrait of Delhi he made this explicit by naming the central British character "Ignorance". But in India at First Sight too he took aim at the narrow world-view of the British, critiquing himself and his own efforts at summarizing the vastness of India in a radio programme:

Yet there were positives too. In Portrait of Delhi the central guide, a native bird, contrasted the earthly boundaries separating the British and the Indians with the freedom availed by creatures of the sky to cross borders with ease.

The bird functioned as a metaphor for the freedom embedded in radio sound to cross airwaves and break through cultural and national boundaries. This was writ large in a scene at the feature’s end: steel birds, or planes, showered Delhi’s landscape with roses, not bombs, as Gandhi’s funeral took place.

The world, noted the bird’s fellow guides, was now a much smaller place:

MacNeice’s features registered the post-empire precipice on which Britain found itself two years after war’s end and as India gained freedom. The loss of the jewel in its crown brought about unease but it also ushered in new possibilities.

For MacNeice, following in the footsteps of Forster and Orwell, it prompted a celebration of the "air" as home to border-crossing birds, planes and radio waves - a territory where propaganda and empire-glorification was slowly but surely giving way to a reshaped global order.