In the two decades of its existence, it’s hard to dispute the sheer popularity of The Black and White Minstrel Show – in numerical terms at least. In the 1960s, it was getting audiences of 16 million. Its stage-show spin-offs were breaking box-office records. At one point, it was even something of a critical success: in 1961, it won the prestigious Golden Rose of Montreux.

What’s harder to fathom is why, in an era in which tens of thousands of black people had long been settled in Britain or were trying to make it their home, a ����ý which had already managed to reflect something of the reality of black British life in documentaries such as 1955’s Has Britain a Colour Bar? and dramas such as 1956’s A Man from the Sun, took so little account of the offence caused by white performers blacking-up their faces on a peak-time TV show.

The traditional defence, namely that it was ‘of its time’, does not quite wash. Even when it launched as a regular series in 1958, old-time American ‘minstrel’ song-and-dance routines were hardly innocent – as this extract from an episode of ����ý’s Timeshift about the show clearly demonstrates:

For the best part of the next twenty years it didn’t seem to occur to anyone in a position of authority at the ����ý that the series really was offensive to more than just a few “killjoys”. This failure to even see any racism was a measure of the ����ý’s real problem: the archival record of its behind-the-scenes thinking during this period is far from flattering.

In May 1967, for instance, the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination submitted a petition calling for the show to be axed. The minutes of a ����ý Board of Management meeting record the Corporation’s head of publicity turning to the letters page of the Daily Mail to gauge the public’s “general view”, and, having adopted this methodology, rather predictably coming to the conclusion that “the programme was not racially offensive”. Apparently satisfied with this, the Director-General, Hugh Greene, decided that “no further action was necessary”.

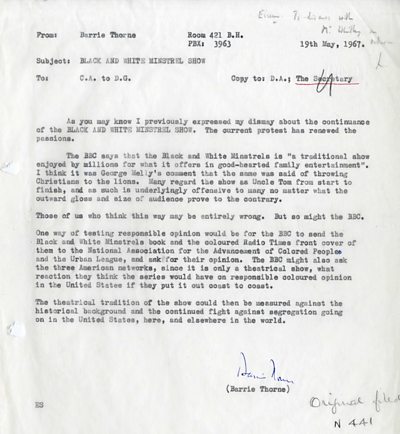

There was at least one determined voice of opposition within the ����ý. The Corporation’s Chief Accountant, Barrie Thorne – who, significantly, had spent some time in the ����ý’s New York office and so had seen something of the Civil Rights movement – argued vociferously for the show to be pulled from the schedule. His memo to the Director-General’s Chief Assistant still survives at the ����ý’s Written Archives Centre:

"As you may know I previously expressed my dismay about the continuance of the BLACK AND WHITE MINSTREL SHOW. The current protest has renewed the passions.

The ����ý says that the Black and White Minstrels is "a traditional show enjoyed by millions for what it offers in good-hearted family entertainment". I think it was George Melly's comment that the same was said of throwing Christians to the lions. Many regard the show as Uncle Tom from start to finish, and as such in underlyingly offensive to many no matter what the outward gloss and size of the audience prove to the contrary.

Those of us who think this way may be entirely wrong. But so might the ����ý.

One way of testing responsible opinion would be for the ����ý to send the Black and White Minstrels book and the coloured Radio Times front cover of them to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Urban League, and ask for their opinion. The ����ý might also ask the three American networks, since it is only a theatrical show, what reaction they think the series would have on responsible coloured opinion in the United States if they put it out coast to coast.

The theatrical tradition of the show could then be measured against the histicial background and the continued fight against segregation going on in the United States, here, and elsewhere in the world."

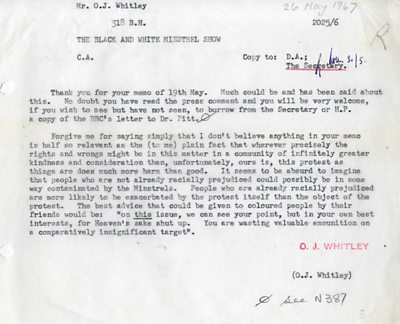

The response Thorne received from the Chief Assistant, Oliver Whitley, was no doubt intended to come across as measured. It contains a standard ����ý response to complaints, namely that whatever the “rights and wrongs” in this particular case protesting was probably counterproductive. But it’s hard not to be shocked by a line towards the end - the suggestion from this senior ����ý figure that “coloured people” should “for Heaven’s sake shut up”:

"Thank you for your memo of 19th May. Much could be and has been said about this. No doubt you have read the press comment and you will be very welcome, if you wish to see but have not seen, to borrow from the Secretary or H.P. a copy of the ����ý's letter to Dr. Pitt.

Forgive me for saying simply that I don't believe anything in your memo is half so relevant as the (to me) plain fact that wherever precisely the rights and wrongs might be in the matter in a community of infinitely greater kindness and consideration than, unfortunately, ours is, this protest as things are does much more harm than good. It seems to be absurd to imagine that people who are not already racially prejudiced could possible be in the some way contaminated by the Minstrels. People who are already racially prejudiced are more likely to be exacerbated by the protest itself than the object of the protest. The best advice that could be given to coloured people by their friends would be: "on this issue, we can see your point, by in your own best interests, for Heaven's sake shut up. You are wasting valuable ammunition on a comparatively insignificant target"."

The ����ý couldn’t exactly say in 1967 that it hadn’t been warned. Tucked away in another part of the ����ý’s written archives is an earlier memo from Barrie Thorne – one he sent five years before. In it, he told the Director of Television, Kenneth Adam, that “The Uncle Tom attitude of the show in this day and age is a disgrace and an insult to coloured people everywhere”.

The problem, he went on to explain, was that so many people were simply “unaware of the offence racial guying can cause”. Adam’s reply came back accusing Thorne of “arrant nonsense”: the show, Adam argued, belonged to that “perfectly honourable theatrical tradition of the British music hall”.

Thorne’s 1962 memo had gone on to suggest that “If black faces are to be shown, for heaven’s sake let coloured artists be employed and with dignity”. It’s unlikely that what he had in mind was The Black and White Minstrel Show itself employing black British artistes. But in the 1970s, so dire were the possibilities for regular employment in television – or indeed in the entertainment industry more broadly – that this was precisely what happened.

In this clip from the Timeshift documentary, for instance, we catch a glimpse of a 1975 appearance on the show by a teenage Lenny Henry:

The presence of black performers on the Black and White Minstrel Show was less a measure of progress than a sign of just how restricted the opportunities were for regular employment.

Even so, time was running out for the series. In part, this was simply because by the late-1970s variety shows in general were proving to be less popular with television audiences than they had been in the 1950s and ‘60s. But there were signs, too, that those involved in making the show were slowly getting some inkling of the offence caused by it:

The very last edition was broadcast in 1978. By then, the Controller of ����ý 1, Bill Cotton, realised he could defend it no longer.

There were inevitable grumbles from its most dedicated fans. Bill Cotton told them firmly that the “racist implication” of its minstrelsy was now obvious to all. “It’s all very well people who are not black saying ‘I didn’t think about it that way’”, he told them, “it’s the people who are black” whose views surely needed to be taken into account.

This might not seem like a revolutionary idea now. But the fact that it was being said at all was at least some measure of the ����ý’s belated, faltering progress in understanding the implications of a multicultural Britain – a full three decades after the arrival of Windrush.