When the ����ý was in its infancy, the line on who exactly got to speak - and who didn’t - was brutally clear. In a memo, dated 3 March 1924, the man at the top, John Reith, sent instructions to all Station Directors - those who controlled output not just in London, but in Manchester, Birmingham, Newcastle, Bournemouth, Cardiff, Glasgow, Aberdeen and in a number of smaller "relay" stations across the country.

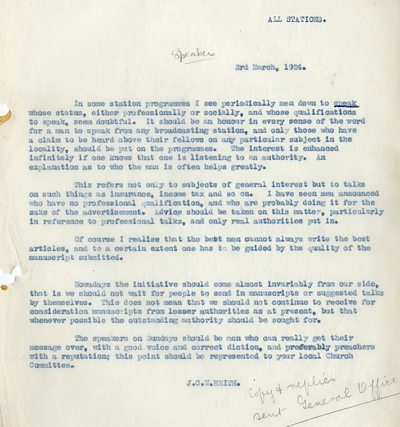

In this memo, shown below, we find Reith declaring that "only those who have a claim to be heard above their fellows" should get access to the microphone:

"In some station prograrmmes I see periodicalled men down to speak whose status, either professionally of socially, and whose qualifications to speak, seem doubtful. It should be an honour in every sense of the word for a man to speak from any broadcasting station and only those who have a claim to be heard above their fellows on any particular subject in the locality, should be put on the programmes. The interest is enhanced infinitely if one knows that one is listening to an authority. An explanation as to who the man is often helps greatly.

This refers not only to subjects of general interest but to talks on such things as insurances, income tax and so on. I have seen men announced who have no professional qualifications, an who are probably doing it for the sake of the advertisement. Advice should be taken on this matter, particularly in reference to professional talks, and only real authorities put in.

Of course I realise that the best men cannon always write the best articles, and to a certain extent one has to be guided by the quality of the manuscript submitted.

Nowadays the initiative should come almost invariable from our side, that is we should not wait for people to send in manuscripts or suggested talks by themselves. This does not mean that we should not continue to received for consideration manuscripts from lesser authorities as at present, but that whenever possible the outstanding authority should be sought for.

The speakers on Sundays should be men who can really get their message over, with a good voice and correct diction, and preferable preachers with a reputation; this point should be represented to our local Church Committee.

J.C.W.Reith."

The airwaves were regarded as a precious commodity, and the implication of Reith’s instruction was clear. They should be reserved for experts and accomplished speakers: the "ordinary" or the unpolished were, to put it bluntly, unwanted.

Even when inexperienced speakers were allowed into a studio, it was only after a laborious process of script-editing and rehearsal. Indeed, standard ����ý practice well into the 1950s was to crush the natural spontaneity out of any broadcast talk. Contributors would most likely be recorded in advance, and their words taken away to be transcribed and tidied up, so that they could then come back into the studio a few days later and read out a scripted version of their original words.

This was only partly about controlling what was said: it was also about the ����ý’s assumption that good communication was something that could only be produced by skilled ����ý staff, even if the desired outcome was, as the ����ý’s guide to speakers put it, the "effect" of spontaneity.

Not everyone inside the ����ý took notice or agreed. In Manchester, especially, there were adventurous troublemakers on the staff wanting to hear working class people speaking on air just as they spoke in real life. This group included Geoffrey Bridson, who made epic features on subjects such as the steel industry. But perhaps the figure most determined to include the unmediated voices of working people was Olive Shapley, who’d joined the ����ý in 1934, working on Children’s Hour.

In this newly-released interview from the ����ý’s Oral History Collection from the North, Shapley recalls how in the 1930s she seized the opportunity presented by a novel piece of equipment - the mobile recording van - to escape the confines of the studio and put-together genuinely ground-breaking programmes.

Two decades later, echoes of both Bridson’s epic style and Shapley’s more democratic technique could be seen on television, especially in the work of Denis Mitchell. His 1959 documentary, Morning in the Streets, made through the ����ý’s Northern Film Unit, offered viewers an "impression of life and opinion in the back streets of a Northern City" as it came to life at the start of a normal working day:

Some of the scenes are clearly contrived. And the model here was still one of people being observed, rather than of people being given direct and unmediated access to speak for themselves or control how their own lives were portrayed.

A move towards such a dramatically different approach only came in the years after 1967, when the ����ý opened a series of local radio stations and phone-ins started to feature on more and more of their schedules. In 1970, Radio 4 launched its own version, It’s Your Line, presented by Robin Day. One senior radio manager instantly declared that the series had "put paid to the myth that opening telephone lines to the public was a recipe for inanity".

The ����ý was still the gatekeeper, of course. Thousands of calls would come in; only a few would make it to the airwaves. Selection - editorial control - was always involved. What on Earth would happen if the ����ý ever abandoned its powers completely?

In 1972, such a previously unthinkable idea took hold in the corridors of Television Centre. And, as this newly-released document from the ����ý archives shows, it was there, on 7 December, that the Director of Programmes, David Attenborough, proposed an extraordinary initiative:

-

Note by Director of Programmes, Television, David Attenborough

Open Door, as the series came to be called, first went on air on ����ý-2 at 11.30pm on Monday 2 April. It wasn’t exactly a peak-time slot. But it gave a platform to marginalized groups. And what made it so radical was not only that the range of voices and opinions and styles of presentation was all suddenly and dramatically expanded; it was also that the ����ý, while providing technical support and airtime, was promising to resist editorial intervention. As long as the law of the land was being observed, anything went.

The idea had involved more than one individual working behind-the-scenes. Naturally, the Director-General, Charles Curran, had kept a close watch. Apart from David Attenborough, other key players included the ����ý’s original cheerleader for local radio, Frank Gillard, the head of the newly-created "Community Programme Unit", Rowan Ayers - who had previously produced Late Night Line-Up for ����ý-2 - and the Controller of ����ý-2, Robin Scott.

Most were anxious at the time, less so, with hindsight. In his interview for the ����ý Oral History Collection, Scott recalls the proposal coming together:

At the beginning, a degree of nervousness was perhaps inevitable inside the corridors of the ����ý. Governors were kept in the dark for as long as possible. Then, in February, 1973 - two months before launch - the man in day-to-day charge of the series, Rowan Ayers, tried to seek Attenborough’s approval for his initial selection of contributors, which included, among others, a "group of black teachers" and members of the "Transex Liberation Group":

The "group of black teachers" mentioned by Ayers had their turn almost straight away - on 16 April 1973. Their chosen presenter was Mike Phillips, who had worked in education but was also a freelance journalist with a little bit of broadcasting experience. Before chairing a studio discussion, interspersed with filmed reports, Phillips provided a graphic introduction to the iniquities of the school system. Nothing like it had been seen on British TV before:

Interviewed in 2018 - some 45 years after his screen debut - Phillips, who spent many years subsequently working for the ����ý before becoming a writer of crime fiction, offers a finely-balanced assessment of whether the programme really was as radical as it claimed:

Open Door, the historian Gavin Schaffer points out, "could never pay anything more than lip service to a truly democratic media". After all, the ����ý did still get to choose which groups made it through the selection process. The episode featuring black teachers might not have happened at all were it not for another key figure in the ����ý’s Community Programme Unit, Tony Laryea.

In this extract from an interview recorded recently for the British Entertainment History Project, Laryea recalls some of the style and content of the first 13 editions of Open Door, his own role at this key moment in the development of "access" TV, and how it shaped his subsequent career:

One serious difficulty with the format soon arose. In setting out to give a platform for groups whose voices were rarely heard, Open Door had to allow on air not just marginalized ethnic minorities but also - if they applied to the ����ý - those who vigorously opposed them.

In 1976, the right-wing "British Stop Immigration Group" had its turn. Its openly racist language created an outcry. As these newly-released documents show, when the episode was due for its Saturday repeat there was a flurry of soul-searching inside the ����ý. First, a hurriedly arranged meeting between the ����ý and representatives of groups opposed to the British Campaign to Stop Immigration:

The most powerful argument against repeating the offending episode was that it constituted an incitement to racial hatred - a suggestion which, if true, would have made it illegal. There were also legitimate concerns that the anti-immigration campaigners who had made the programme had direct links with at least two right-wing political parties - something that breached the programme’s own terms and conditions.

The ����ý countered that lawyers had cleared the programme, that it was unlikely a single programme could ever have the effect that was being claimed anyway, and that a "basic right" to freedom of expression was at stake. The repeat went ahead.

Two years later, after an entirely different complaint, the Director-General Ian Trethowan was forced to write to the City of Portsmouth. His letter’s important not so much for the details of the case but for what it reveals about how the ����ý defended the various groups who appeared on Open Door, or, more precisely, how it defended its own editorial position:

Trethowan’s closing remarks are striking. He admitted that the ����ý knew from the start that Open Door would create headaches. But, he added, the ����ý had also concluded that ""access" broadcasting was an important concept and should be included in our schedules, whatever problems it might cause". From a conservative figure such as Trethowan, this was a brave statement of principle.

The kind of approach pioneered by Open Door undoubtedly stimulated some deep editorial re-thinking at the ����ý. This can be seen vividly in a highly reflective document drawn up in 1976 by Paul Bonner of the Community Programme Unit. One hundred episodes into the ����ý’s experiment, it explored the pitfalls and the potential of broadcasting unheard and controversial voices in a society "increasingly divided against itself":

Where might "access" broadcasting lead next, Bonner wonders. Some sort of answer can be heard in this interview from the ����ý’s Oral History Collection recorded in 1985. In it, Stuart Hood, who had been a strikingly progressive figure when he was in charge of television programmes in the early 1960s, offers a typically radical analysis.

He speaks of a crisis in public broadcasting caused by the very divisions which Bonner had written about 9 years earlier. Peering into the future, he suggests the need for a much broader restructuring of the media eco-system:

Hood concluded that "access" programmes were something of a dead-end. But for the ten years in which Open Door ran on ����ý television, it arguably had an effect out of all proportion to its place on the schedule. And for those most intimately connected with it, such as Tony Laryea, there was certainly evidence enough of its significance, for both the institution that launched it and the small but dedicated audiences who watched it:

Further reading

- Stephen Bourne, Black in the British Frame (2001)

- Stephen Bourne, Mother Country: Britain's Black Community on the Home Front 1939-45 (2010)

- Stephen Bourne, War to Windrush: Black Women in Britain 1939 to 1948 (2018)

- Darrell M. Newton, Paving the Empire Road: ����ý Television and Black Britons (2011)

- David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016)

- Gavin Schafer, The Vision of a Nation: Making Multiculturalism on British Television, 1960-80 (2014)

- Wendy Webster, Mixing It: Diversity in World War Two Britain (2018)

Public Attitudes

-

Public Attitudes

How did broadcasters’ attitudes to race compare with those of the British public at large? We dip into some of the evidence from the ����ý’s own audience research files and the pioneering social research organisation Mass Observation.

Related links

-

Second Wave Feminism This collection of television and radio programmes remembers some of the major feminist thinkers of those years and highlights the issues they addressed and attitudes they contested.