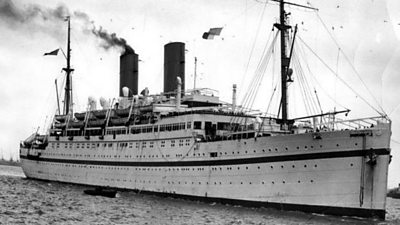

The Empire Windrush’s arrival at Tilbury Docks on 22 June 1948 - and the disembarkation of the 492 men who had travelled on it from the West Indies - was captured in newsreel images and sounds that have since become iconic:

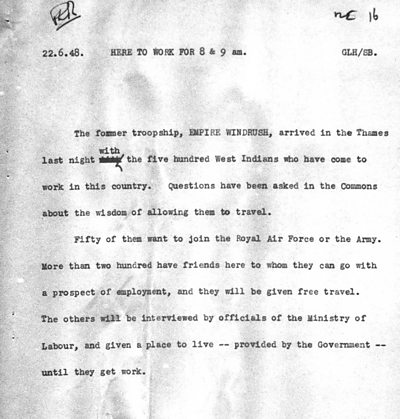

Yet, Windrush wasn’t always as prominent in the nation’s consciousness as it is today. Even on its arrival, the ����ý Home Service reported on the day’s events in a noticeably subdued manner - as these news bulletin scripts from 22 June 1948 reveal:

The former troopship Empire Windrush, arrived in the Thames last night with the five hundred West Indians who have come to work in this country. Questions have been asked in the Commons about the wisdom of letting them travel.

Fifty of them want to join the Royal Air Force or the Army. More than two hundred have friends here to whom they can go with a prospect of employment, and they will be given free travel. The others will be interviewed by officials of the Ministry of Labour, and given a place to live - provided by the Government - until they get work.

Click on the links below to see the Home Service news bulletin scripts for 1.00pm, 6.00pm, 9.00 and 10.00pm.

The handwritten numbers in the corner of each page are telling. They indicate where the story was located in the running-order that day. At breakfast time; number 16, almost last before the sport; at 6pm, it soars to number 3; later in the evening it’s back down to number 16. It was what news editors call a "mid-bulletin" story. There are ripples of reaction in the days and weeks that follow. And then barely a mention for years - until 1974, when the newsreel featured above was included in a ����ý documentary, The Ship of Good Hope.

In 1998, however, Mike and Trevor Phillips published Windrush: The Irresistible Rise of Multi-Racial Britain, and the book helped inspire a whole season of programmes on ����ý television. As a result, fifty years after the ship’s arrival, British audiences were exposed in compelling detail to the myriad first-hand testimonies of those who had been on board: their hopes, their fears, and, in many cases, the difficulties they subsequently experienced finding acceptance in their new homeland. Here is a short section from one of these 1998 programmes, the opening edition of the documentary trilogy, Windrush, produced by Trevor Phillips:

The ����ý’s embrace of the Windrush story - even if rather belatedly - made sense. The ship’s arrival in 1948 was certainly not the beginning of ethnic diversity in Britain. There had been a rich Black and immigrant presence for centuries. But it was a symbolic beginning to much of what followed: the old Imperial "Mother Country" becoming home through the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s to thousands of immigrants from its former colonial "outposts" - the Caribbean, Kenya, Uganda, India and Pakistan - and the need for its citizens to reimagine what it meant to be British. For a national broadcaster such as the ����ý there had always been the need to think hard about who got to speak on air and whether the full range of identities and opinions was really being represented.

Now there were new challenges. The ����ý had often seen itself as a force for uniting the nation. Yet it had also become a place where differences get aired. As one of its recent Directors-General, Mark Thompson, has said, when Britishness is being discussed "the ����ý is one of the one of the main arenas in which this discussion takes place".

Broadcasting could never be an entirely neutral arena. It was part of the world of image-making and opinion-forming. The people who make programmes are also often driven by a desire to "make a difference". As the historian Gavin Schaffer suggests, governments and broadcasters firmly believed in the power of the ����ý - and ����ý television, especially - to "intervene and instruct" in social affairs. The question, though, was surely this: would the ����ý paper-over differences or draw attention to them? Would it worry about them or celebrate them?

One important story that the archive material collected here reveals very strongly is that even before the arrival of Windrush, ����ý programmes were not quite exclusively white. Go back to 1934, and we find The Times excitedly reporting ����ý Radio’s first broadcast by the Guyanese Rudolph Dunbar and "his Coloured Orchestra".

On the opening night of ����ý television, 2 November 1936, there was an appearance by Buck and Bubbles (above), an African-American double-act, described in the Radio Times as "a coloured pair" who "dance, play the piano, sing". And two years later, the Guyanese actor Robert Adams was cast in the leading role in a production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones. Other African-American performers seen on screen in this early period included Elisabeth Welch, Paul Robeson, Nina Mae McKinney, and Adelaide Hall (pictured below).

In a short, filmed interview, the man in day-to-day charge of programmes from the ����ý’s Alexandra Palace studios, Cecil Madden, provides some useful insight into the presence of such African-American stars. It was, he suggests, the sheer quantity of high-class entertainment being staged in London’s West End in the 1930s that provided a convenient reservoir of talent from which the ����ý could draw:

The outbreak of War disrupted West End theatres - and shut down television completely. Yet, in principle, the opportunities for more ethnic diversity on air multiplied. Alongside the several thousand Black Britons who had been born in the country, there were now some 12,000 men and women from across the West Indies who had come to serve in the British forces, and by the eve of D-Day in June 1944 another 130,000 African-American GIs stationed around the UK. Some appeared regularly on ����ý services transmitted overseas, but regular appearances on serious ����ý programmes for home audiences were rare.

Throughout the War and immediately after, African-American or Caribbean men and women continued to feature almost exclusively as performers in musical shows, light entertainment or drama.

Nevertheless, there were some striking moments. in June 1946, the Trinidadian actor Edric Connor, who had appeared regularly on wartime radio programmes such as Songs of the West Indies and Serenade in Sepia, was seen introducing the "Ballets Nègres" on the ����ý’s recently re-opened TV service (pictured below).

The historian David Olusoga has suggested that the experience of meeting black GIs, fighting alongside men and women from the black colonies, and discovering the full implications of Nazi racial policies all helped change attitudes in Britain - that, in short, the Second World War made "racism less acceptable." But, he adds, "not everywhere and not instantly".

The ����ý’s own record was certainly mixed. We find, for example, senior editors worrying away over comedy scripts. In 1943, producers were carefully reminded that:

there are a lot of coloured people in the country now - Africans, West Indians and Americans - and that there is therefore particularly good reason to be careful not to say anything which might be interpreted as showing colour prejudice.

This reveals sensitivity from the top. It also hints at the frequency with which transgressions occurred. We know, for instance, that two years previously, a comedian in a ����ý radio sketch had poked fun at someone who "marries a darkie". If ����ý managers showed a desire to stamp-out racist stereotypes, they also betrayed an inability to enforce their own guidelines effectively.

For programme-makers of all kinds, racial prejudice - and the so-called "colour bar" - was increasingly a subject of interest in itself. Windrush coincided with the era of post-war austerity, and in some parts of the country immigration was all too often being blamed for causing a shortage of jobs or housing. As a ����ý radio producer warned, prejudice on the basis of colour was in danger of serving "a political end". Can "revulsion" at those who appeared different be "overcome", she asked her colleagues, and if so "how?"

One possible answer was through drama, and its power to encourage a little more empathy. In 1956, the ����ý screened A Man from the Sun, a "Story of West Indians in London" written and produced by John Elliot. In this scene, very near the beginning of the drama, we see Nadia Cattouse as Nina and Cy Grant as Alvin, receiving news of the imminent arrival in London of Alvin’s cousin Cleve:

A Man from the Sun has been criticised for underplaying the sheer extent of racial prejudice that new settlers had to face. But those opening scenes managed, in just a matter of minutes, to signpost all the drama’s key themes: the struggle to find work in the face of white prejudice, a desire to integrate being overtaken by growing disillusionment, and the role of the "community" in fighting for social justice.

Across the country, nearly forty per cent of all adult viewers watched it. And when the ����ý asked a sample of this audience what they thought, a majority admitted to thinking that West Indian immigrants deserved more sympathy and understanding, not less than before.

Yet drama could only do so much in the face of some harsh realities. The previous year, in an episode of the ����ý current affairs series Special Enquiry, the reporter René Cutforth had posed the question: Has Britain a Colour Bar? The answers he unearthed in Birmingham were hardly encouraging - even though his tone tried hard to be positive, grasping for solutions:

Cutforth's programme drew an uncomfortable and stereotypical distinction between Asian and West Indian immigrants, lauding the former for their entrepreneurial spirit and so, implicitly, blaming the latter for a lack of it. But his real theme was the prospects for integration or rather, the very real prospect of integration failing.

For, despite the relatively small figures for net migration throughout the late 1940s, ‘50s and early ‘60s, the volume of anti-immigration rhetoric was rising, especially among the political class. There were real consequences. In the late summer of 1958, ����ý TV news bulletins reported no fewer than 32 times on attacks on black people’s homes and roaming white lynch mobs in Nottingham and Notting Hill in the space of just four weeks.

One strategy among broadcasters was to attempt to rise above the fray and behave as if race could be transcended as an issue. The early-evening news magazine Tonight, for instance, regularly featured Cy Grant performing a topical calypso for viewers. The musical form was stereotypically Caribbean. But as the closing moments of this edition from 27 April 1959 show, Grant’s own identity was not in itself considered worthy of comment:

A different strategy was simply to support more actively the cause of integration before it was too late. And after witnessing the incendiary use of racial prejudice during the 1964 election campaign in Smethwick, the Labour government vigorously pursued the goal of enlisting broadcasters. At the end of January 1965, the Postmaster-General Tony Benn wrote to the ����ý's Director-General, Hugh Greene, enclosing an article from the Guardian.

The article had suggested that the ����ý might consider a regular programme for immigrants "telling them how to adapt to life in Britain". Benn then told Greene that this presented "a most interesting possibility which you will no doubt wish to examine". Greene’s first response was to cast doubt on "the wisdom of doing anything which might tend to emphasize the apartness of coloured immigrants". But he quickly sought the advice of the Institute of Race Relations, whose head told him there "should be special programmes".

Greene prevaricated, worrying that such programmes might do more harm than good by irritating the "general audience", and speculating that local broadcasting, not national broadcasting, might be the appropriate place for this kind of output. The Postmaster-General then referred the matter to a fellow Minister with special responsibility for immigration, Maurice Foley.

What then happened behind-the-scenes can be traced in the following ����ý documents. In the first, dated 19 May 1965, the Director-General reports on a meeting he had had with Mr Foley:

The two "conferences" which Greene promised the Minister took place in July, and were designed to elicit the opinions of immigrants themselves. The first, held in Broadcasting House on Tuesday 6 July, involved representatives of the Indian and Pakistani communities in Britain, and is recorded by the ����ý in this 11-page "note":

The second, a week later, involved representatives of Britain’s West Indian communities:

Both meetings revealed a desire to see television used for any new initiatives, not just radio - and certainly not just local radio, as Greene would have preferred.

But a crucial split had also emerged. Most of the delegates at the "West Indian conference" worried that special programming would heighten a sense of separation from Britain at large. Representatives from the Indian and Pakistani communities were keener.

The result, as the historian Gavin Schaffer points out, was that programmes specifically for Black Britons were "off the ����ý’s radar for over a decade". And, as we see in Part 2, when the ����ý did hurriedly launch its first ever series for immigrants only a few months later, it would turn out to be only for Asian viewers and listeners.

Further reading

- Stephen Bourne, Black in the British Frame (2001)

- Stephen Bourne, Mother Country: Britain's Black Community on the Home Front 1939-45 (2010)

- Stephen Bourne, War to Windrush: Black Women in Britain 1939 to 1948 (2018)

- Darrell M. Newton, Paving the Empire Road: ����ý Television and Black Britons (2011)

- David Olusoga, Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016)

- Gavin Schafer, The Vision of a Nation: Making Multiculturalism on British Television, 1960-80 (2014)

- Wendy Webster, Mixing It: Diversity in World War Two Britain (2018)

Harlem at the ����ý: 1964 as a year of change

-

Harlem at the ����ý: 1964 as a year of change

African-Americans had appeared on British television screens since the 1930s mostly as entertainers. But there were also remarkable examples of African-Americans getting a leading role in harder-hitting programmes about Civil Rights - and exposing British audiences to the brutal realities of racial prejudice.

Related links

-

Witness: The Voyage of the Empire Windrush ����ý World Service

-

Caribritish: Children of Windrush ����ý Radio 4

-

Mobeen Azhar: Windrush ����ý Asian Network

-

1Xtra Talks: Windrush 70th Anniversary ����ý Radio 1Xtra

-

Black and British Season ����ý TV and Radio