Horizon is the most significant, and the longest-running, multi-theme science documentary series ever, the yardstick against which all others are measured. The first programme, The World of Buckminster Fuller (produced by Ramsay Short), was broadcast on 2 May 1964. Now sixty years old, more than 1,100 programmes have been broadcast in the strand.

Buttonhole rather than lecture

If you go back to the early sixties and eavesdrop on the producers' conversations, which are preserved in thick files at the ����ý's Written Archive Centre, there is no sense that they were setting out on a half-century project. But the papers are fascinating, as they reveal the main people involved – Aubrey Singer, Philip Daly, Gerald Leach, Gordon Rattray Taylor and Ramsay Short, with interventions from Michael Peacock – hammering-out what a science programme for the modern world of the 1960s should be like.

There had been many science programmes on the ����ý before 1964, but this one had to be different. So they resolutely turned away from the style of earlier programmes such as Science is News or Eye on Research and set out to copy the era's most successful and popular arts magazine series, Monitor.

In copying this, the production team determined to make a programme that was focussed on the culture, ideas and personalities of science. They rejected being driven by the news agenda and they refused to be didactic. As Gordon Rattray Taylor, its editor in 1965, proposed: "It will buttonhole rather than lecture"; the programme would say "It's rather interesting that…" rather than "Tonight we are going to tell you about…".

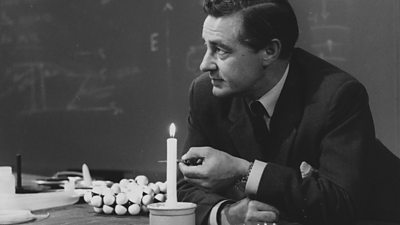

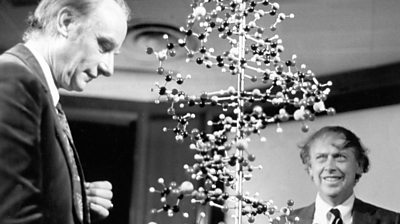

As a person-centred account of science, it was interested in what kinds of people scientists are, and so a fair few of the early programmes were centred on particular scientific personalities, including Buckminster Fuller, Michael Faraday, Jacob Bronowski and Peter Medawar, or groups of scientists such as The Tots and the Quots, a dining club convened prewar by the primatologist Solly Zuckerman.

The magazine years

The first few years were distinctly shaky. Copying Monitor meant Horizon should be a magazine programme presented by an anchorman, but all attempts to find a scientist to fill this role failed, and the first programmes broadcast in 1964 generally got round the problem by making programmes with linked themes, united by voiceover narration.

For a couple of years from 1965, the producers did manage to make Horizon as a magazine programme, presented by the journalists Colin Riach and Christopher Chataway. But, having achieved their aim, everyone decided it wasn't terribly successful.

Under its third editor, Robert Reid, it stopped being a partially-live magazine programme and adopted the form that many of us will remember; film documentaries on single themes with the content shaped by the voice of an off-screen narrator. For many years this role was filled by the reassuring tones of the journalist Paul Vaughan.

The televising of science

It's difficult to sum-up such a vast phenomenon as Horizon, and especially its relationship to science. But a keynote was struck in 1966 by Aubrey Singer, head of the science department, when he argued in a ����ý lunchtime lecture that

...the televising of science is a process of television, subject to the principles of programme structure, and the demands of dramatic form. Therefore, in taking programme decisions, priority must be given to the medium rather than scientific pedantry.

In other words, Horizon and other science programmes were part of the business of television. The way that Horizon producers interpreted this principle was to think of themselves as investigative journalists, always looking for a good the story that would structure a programme.

Attitudes to science

Until the end of the sixties, the programme was consistently highly respectful of scientists, a preference that was reinforced by the six-monthly formal meetings of the newly-formed Science Consultative Committee, where senior scientists discussed programming with senior ����ý producers. Science and technology were most often presented as a source of progress and prosperity for the world at large.

This trend culminated in the 1968 programme Black Man – White Science (produced by Anthony Isaacs), which explained the domination of the world by the West as being the product of the unique features of western culture which gave rise to modern science and technology. But, towards the end of the sixties, several issues in the public culture of science became prominent: transplants, chemicals and biological warfare, the environment, for example.

All these debates led journalists and people in general to start questioning the direction that science was taking. And Horizon producers took part in this critical turn, interrogating the very notion of scientific progress. Examples include such programmes as For the Safety of Mankind (1969, produced by David Rea), telling of a group of people who thought it to be their duty to pass nuclear secrets between the West and the Eastern Bloc to stop the arm race.

A penchant for pessimism

In the early seventies, Horizon was often charged with having a "penchant for pessimism". This was, according to the editor at the time, Peter Goodchild, a consequence of the development of story-telling techniques based on finding a dramatic centre point for the programmes.

For example, The Planets (1975, produced by Edward Goldwyn), discussed, amongst other topics, the role of big asteroids' impacts in shaping the planets in the distant past, and thus evoked the possibility of such an event in relation to the Earth in the present. Throughout the eighties and nineties Horizon continued its questioning of the social consequences and the politics of scientific and technological innovation.

Yet, at the same time as Horizon pointed to the dangers of unchecked science and technology, such programmes as The Cruel Choice (1983, produced by Sophie Robinson and Fanny Prior) which discusses the necessity of animal experimentation for the advancement of science and human well-being, or A New Green Revolution? (1984, produced by Martin Freeth), which examined then new efforts at reforming poor countries' agriculture.

It suggested that, as long as they are properly controlled, science and technology are efficient means of bettering the human condition.

Re-shaping Horizon

Thanks to the editorial independence granted to the successive editors of the series, throughout these three decades producers could range across science and its implications, ever in search of a good story. Each producer could develop their own style and follow their own ideas, contributing to Horizon's diversity.

At the end of the 1990s, the beginning of the 2000s, Horizon's relevance was increasingly questioned, and the programme was reshaped as a consequence. Storytelling became central to the construction of each edition, science becoming an element in the story, instead of necessarily being the main topic of the programme.

This evolution led to some interesting developments whereby Horizon commissioned scientists to perform research or experiments specifically for the programme, making science a televisual event. For example, for the 2004 programme The Truth about Vitamins (produced by Dan Kendall), research was commissioned to investigate whether food supplements and other 'Natural remedies' were beneficial or if they were causing harm.

Increasingly in the last two decades, Horizon has tried to show science in the making, taking cameras alongside scientists, and becoming a witness of the scientific enterprise. In this it has made some return to its origins. We often now see presenters; perhaps Brian Cox in his 'favourite science teacher' mode, infinitely less aloof than the elite scientists of the early years, or Michael Mosley conducting a new, punishing, self-experiment as a first-person journalistic account of science.

Like some of the very earliest programmes, such as Science, Toys and Magic, Ramsay Short's Horizon Christmas special in 1965, Horizon today often enjoys considerable critical praise. Here's to the next 60 years!

Further reading

-

An interactive eBook

Find out more about Horizon

-

Horizon at 60

A celebration of the long-running science programme by Dr Tim Boon and Dr Jean-Baptiste Gouyon from The Science Museum. -

The other side of Horizon

The science programmes that came before -

Horizon 60 interviews

A sequence of interviews with the makers of Horizon over its 60 years.