One man’s mission

In a chapel in the heart of the south Wales valleys, a coffee morning is in full flow. It is a small affair - just a handful of retired men exalting the glory days when the mines were still open. Today, like most weeks, numbers are relatively low. But for the minister who has organised it, the Reverend Robert Stivey, it is still something of a triumph.

Just a year ago, this chapel - the Calfaria Calvinistic Methodist Chapel in Porth - was shut, its future uncertain.

Like so many other chapels in the valleys, it was lying empty, awaiting demolition or conversion into flats.

However, Stivey stepped in, purchasing it for under £40,000 of his own money, then re-opening the vestry to allow life in once more.

“The chapel secretary was 90 when she retired,” he says. “No-one wanted to take on her role. But I take great pleasure in seeing the chapel coming alive again, bringing people back.”

This is one of 12 chapels he has bought across the south Wales valleys over the past decade, spending roughly £200,000 of his own savings.

His aim is to re-open them all, or at least keep them in safe hands until the congregations return.

“I am intent on attracting new fellowships,” he says. “Spreading the Gospel and using these chapels not as museum pieces, but centres of worship.”

He pauses then smiles.

“What I need to express is that this project is not about me or even the chapels. This is about the Lord and this is my calling.”

It is an ambitious calling, but one which Stivey seems to have spent much of his life preparing for.

Growing up in Plymouth, he frequently attended Sunday school until his personal faith was cemented at the age of 16.

Driven by his interest in historic buildings, he began work as a chartered surveyor.

He married and became the father of five children, one of whom died and another who was involved in a traffic accident and left quadriplegic, with just the use of his right limb.

“We thought he would die,” Stivey says. “But there was a lot of praying by his bedside and he survived. Now he comes down from London in his wheelchair and helps me run the chapels.”

It was only in his 60s that Stivey began dedicating his life full-time to his faith, working as an ordained minister in the Islington area of north London.

Something else came into his life at that time - a run-down cottage in the village of Merthyr Vale, just five miles away from the former iron capital of the world, Merthyr Tydfil.

“My wife and I bought this cottage and began coming frequently,” he says. “But while I was travelling around, I noticed all these chapels shut down or up for sale. They were just being demolished, or used inappropriately.

“An idea began to germinate and I thought that someone should be doing something about that. And then I got a message, or feeling, from the Lord, that that person was me.”

In its heyday, the valleys boasted roughly 2,000 chapels, tending the souls of those who moved there to work in the coal mines.

Not only were these chapels religious hubs, they had a significant influence on cultural, educational and political life, with eloquent preachers creating theatrical atmospheres that could radicalise congregations.

Prominent nonconformists like John Hughes wrote some of Wales’ most famous hymns such as Cwm Rhondda (often known as Bread of Heaven), and chapels are credited as being incubators of Welsh culture and language, steadfast in fuelling the likes of the National Eisteddfod.

The number of chapels was so high because there were so many different non-conformist denominations. Some offered language in Welsh, others in the English language.

They often boasted charismatic preachers and offered a strong sense of community, but by the 1920s and 30s, a decline was under way.

Dr Gethin Matthews, senior history lecturer at Swansea University, says, “The last hurrah for the religion really was 1905 when a Christian revival swept Wales. After that came a general decline in organised religion.

“The valleys were hard hit. Not only was there depopulation as mines shut but many of those who came back from World War One became disillusioned with the chapel message that it was a ‘just’ war.

“Society then evolved and moved on with more modern forms of entertainment, and chapels began to be seen as dogmatic and old-fashioned.”

All this may be history, yet the consequences are clearly visible today.

Take a drive across the stunning - yet bleak - landscape, dipping into the deprived, ribbon towns known for their close-knit communities, and abandoned chapels are everywhere.

Many are Grade II-listed but still falling into ruin. Others have no such protection, and can be demolished at a developer’s whim.

Typically, they come up for auction or appear on estate agents’ websites. And this was where Stivey found his Porth chapel, snapping it up in 2010 as his first project.

In many ways, it has proved to be his most successful venture. He has established a weekly service, free coffee mornings, a ladies’ group and a children’s club.

The number of people attending these events, however, is rarely out of single figures and they all take place in the vestry, or hall, with the chapel itself lying empty and abandoned upstairs.

To walk around the silent pews and gallery - built for 500 or more - is to step back in time.

There’s the smell of dust and pitch pine. There are children’s names scratched into the backs of pews. Cushions and crocheted blankets remain on some seats, saving places for people unlikely to return.

In the quiet of the chapel, Stivey’s eyes drift beyond the pulpit to the organ - glorious but unplayed, its metal pipes painted in soft pastels.

Above him, high on the ceiling, is a decorative rose.

“The aim is to leave the vestry and move back here,” he says, wistfully. “But we will need 50 or 60 people for that, and I don’t think we shall ever see the hundreds needed to fill the gallery upstairs."

It is this quest for fresh congregations that is the key challenge for Stivey.

And never is this clearer than 15 minutes’ drive away at the Tabernacle Chapel in Treharris, where the only thing that breathes life into the stone walls is death.

On a rainy Thursday morning in September, a local funeral attracts 30 or so black-clad mourners.

Father Gareth Coombes, an Anglican priest who takes services for all denominations in the region, greets those who step through the doors before the hymns ring out.

“The church has lost connection with communities,” he says. “We can’t expect people to go to church in the same way. Kids have sport on Sundays.”

Still, since Stivey re-opened the doors in 2018, funeral services have become popular.

“It’s memories,” says John Davies, the funeral director. “People and their families have links to the chapel going down generations. So when someone dies, they want the funeral there even though it’s not usually open.”

However, he is not optimistic about the chapel’s long-term viability: “It just isn’t catching on as a place of worship.”

His assistant, Sophie McCarthy, 24, says, “People might want the chapels open but no-one wants to pay for their upkeep. Even at services, you pass the donation box around and people just look at it and carry on walking.”

Besides the size of the congregation, money is certainly the biggest issue for Stivey.

Another of his chapels is a modern building in the village of Aberfan, site of the 1966 landslide which killed 116 children and 28 adults.

Built in 1970 and closed in 2007, it lies vandalised and partially flooded, with smashed windows and ivy snaking in through damaged brick.

Anything of value - electric and copper cables plus lead from the roof - was stolen long ago.

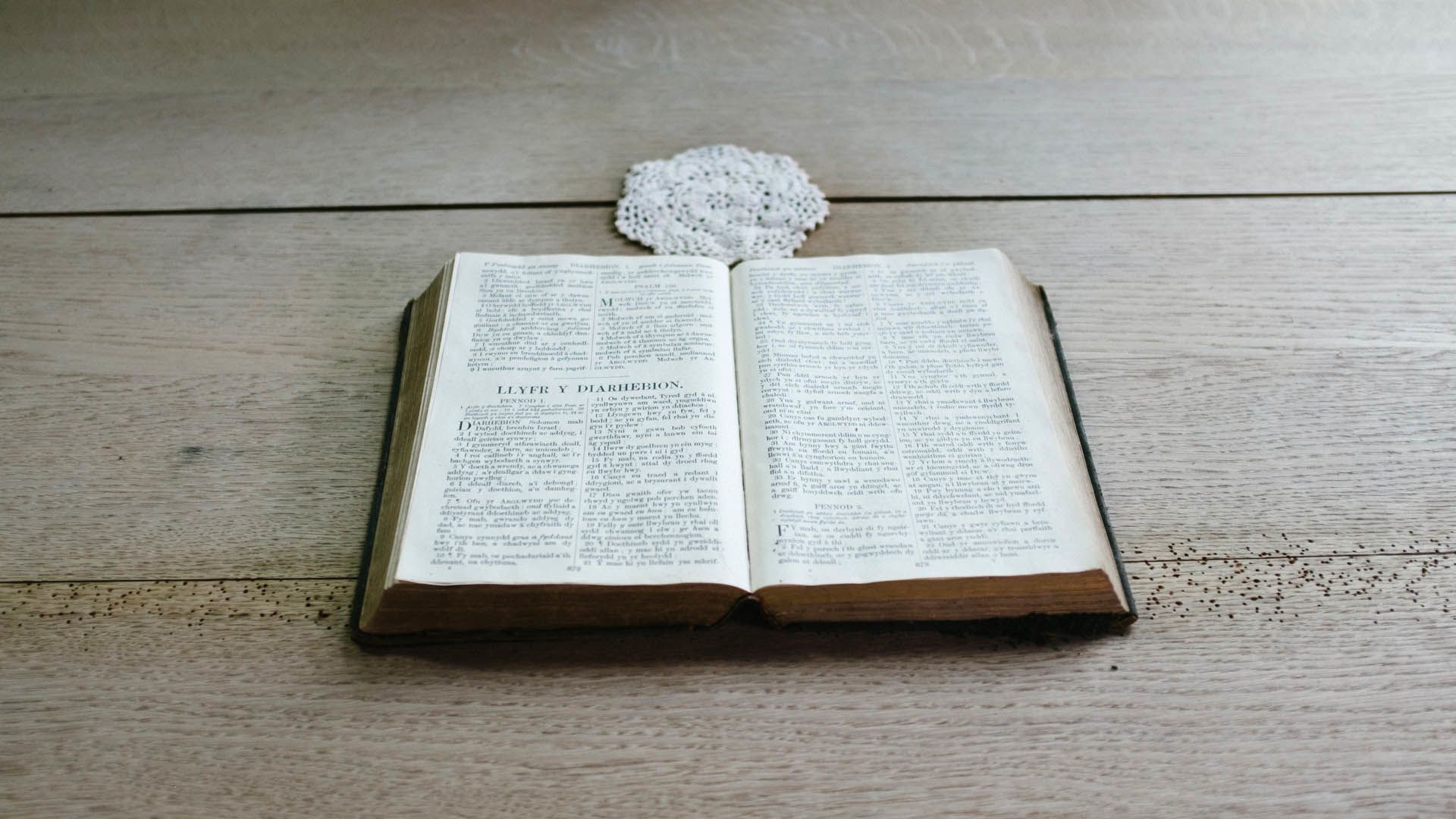

All that remains for now to remind people of the building’s purpose is a hefty Bible lying open on a table.

It seems an anachronistic sight, just like the nearby coal lorry delivering bags of coal door-to-door.

But for Stivey, it is crucial to his plans.

“The building certainly is an eyesore,” he says after attempting a faint-hearted clean-up, “and a sorry tale with all the vandalism. Still, I leave this old Welsh Bible open at the front. To many this may be a derelict building, but to me this is still the house of God.”

Many of his other acquisitions – all individually purchased for between £1,000 and £39,000 - hold similarly sorry tales.

In Merthyr Tydfil, the Seion Welsh Baptist Chapel of 1788 once held 1,000 people.

The roof is leaking, and dark boards are pinned to the windows to deter pigeons.

Mountain Ash’s Bethania Chapel - where some claim the great Welsh hymn (and rugby anthem) Calon Lân received its first public airing in 1892 - is now used to store furniture for a local charity.

In Aberdare, the Calfaria Baptist Chapel with its prominent WWI memorial is closed, a pile of litter stacked up by doors leading to an overgrown graveyard.

This chapel, one of his newer acquisitions, cost him £25,000.

But is it a hopeless case? Not so for the minister.

“We clearly need to renovate and reopen,” he says. “And it will be a slow process, perhaps not even done in my lifetime.

“But I am happy when I come here. It is spiritual heritage. I sit here and think of the past, with all the singing and worship. As long as it’s not broken into and vandalised, I am happy.”

Some of the chapels are in better condition.

The Siloam Welsh Baptist Chapel, in the village of Penderyn, closed after worshippers fell to single figures, but it is in near-perfect condition - small and intact, with no damp or damage.

“This one,” says the minister, gazing up at the pulpit, “is ready to go. We could open it tomorrow. All we need is the people.”

But in the three years he’s owned the chapel, Stivey hasn’t been able to entice back a congregation. It has stood empty, with no worship, oratory or singing to bring the acoustics to life.

This leads to an inevitable question - will he ever be able to accomplish his mission to reignite the congregations and spread God’s word as he wishes?

Twenty minutes away, back down in Porth, the locals are ambivalent - there’s support for the minister but also a hard view of practical realities.

Serving at the local chippy, Norma Seldon’s view is typical: “We all went to chapel on a Sunday and it’s sad they are closing. No-one wants to see them turned into flats, but I’m not sure who will go?”

For the minister and those who support him, however, there is a clear and compelling point, and it is this that drives him on.

It is a mission that has involved sacrifice.

Not only has Stivey spent all his inheritance on the chapels, he is also reliant on public transport to check on them - a “laborious and time-consuming task” that takes up most of his days.

His wife now has dementia, and is cared for in London, and he is all too aware that he is away from home.

“I never thought I would end up here in the valleys,” he muses, from his digs in Treherbert. “But the Lord moves us around.”

These issues are nothing when pitted against his calling, however.

“Some people don’t think you need a chapel in every town anymore,” he says, “but we need to provide for the local community a place where the Bible can live.”

Does he ever feel daunted by the task?

“I feel completely at peace and incredibly privileged to save [the chapels]” he says. “And what is more, I’m amazed by the amount of interest in them. Of course some people are cynical, saying I am eccentric and outlandish and that it will never happen. But what I say to them is, 'have faith, have faith'.

“I am never daunted by the scale of the project, not ever. The Lord will provide.”

Credits

Writer: Gwyneth Rees

Photographer: Christian Petersen

Photo Editor: Phil Coomes

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

More long reads

The people who live on remote rocks in the North Atlantic

Aberfan: The mistake that cost a village its children