Tartan Noir: A very strange beast

12 August 2016

With ten Logan McRae novels under his belt, Aberdonian crimewriter STUART MACBRIDE is firmly established as an international bestseller. His books, along with fellow Scottish writers' novels, have been dubbed Tartan Noir. As the Edinburgh International Book Festival gets underway, the author investigates what lies behind this publishing phenomenon, and whether it really exists at all.

By Stuart MacBride

According to Tartan Noir, Scotland is littered with dead bodies, awash with serial killers, and populated with dour-faced police officers out to win justice for the dead.

Tell a Scotsman or Scotswoman to do something and, nine times out of ten, we鈥檒l do the exact opposite. Because we鈥檙e thrawn

And as I’ve been writing this stuff for a decade now, I guess I have to shoulder some of the blame.

But is it really that grim? Well … no. And I’m not just talking about the country – which is lovely, especially if you like things deep-fried in batter – I’m talking about Tartan Noir itself.

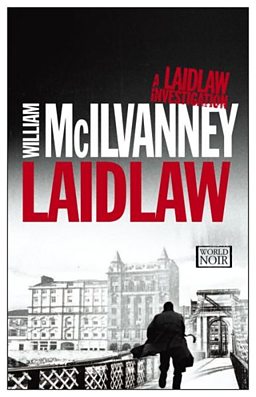

Let’s jump back in time to the 1990s when the term was coined, either by James Ellroy or Ian Rankin (depending on who you believe), and a whole new genre was born. A genre that traced its roots back to the work of William McIlvanney.

McIlvanney had achieved a fair amount of literary success before turning his attention to crime fiction with his Laidlaw novels.

While crime fiction south of the border was still obsessed with ‘Golden Age’ writers like Agatha Christie, McIlvanney’s Laidlaw was closer to the American hardboiled tradition. No locked room mysteries and ‘it’s a fair cop, guvnor’ endings here. This was about darkness and nuance, where not even the protagonist was without blame.

He only wrote three crime novels: Laidlaw, The Papers of Tony Veitch, and Strange Loyalties, but he’s now widely acknowledged as the ‘Grandfather of Tartan Noir.’

These were the books that inspired Rankin to try his hand at crime fiction, and he, in turn, went on to inspire the next generation of Scottish writers. Including me.

Rankin’s Detective Inspector John Rebus, with his hard drinking and his philosophising and his disrespect for authority is cast from the same mould as DI Jack Laidlaw. Men battling against the system, who only see the world in terms of black and white when it suits them.

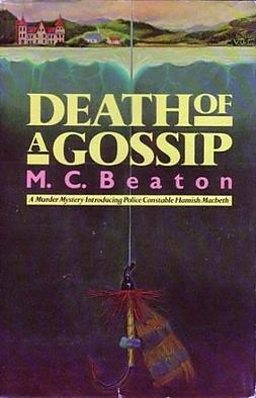

But they’re not the only ones in the chain of Tartan Noir: M.C. Beaton’s Sergeant Hamish Macbeth first appeared in Death of a Gossip – two years before Rebus appeared on our bookshelves – and he has those same core character traits. He’s not as hard and brash as Rebus or Laidlaw, and he has a much better sense of humour, but he has the same disrespect for authority and moral flexibility when it comes to getting the right result.

It’s that disrespect for authority that really stands out in Tartan Noir. It’s a cornerstone of our identity as a nation.

Tell a Scotsman or Scotswoman to do something and, nine times out of ten, we’ll do the exact opposite. Because we’re thrawn. It’s a word that runs right through us, like the letters in a stick of Blackpool rock, and it’s a character trait that appears time and time again throughout Tartan Noir. Our protagonists are thrawn.

The thing is, that’s pretty much the only thing these books have in common – other than the fact they’re usually set in Scotland.

Tartan Noir isn’t so much an umbrella term for a select few writers to shelter under as it is a dirty-big marquee. It covers everything from the acerbic satire of Christopher Brookmyre’s Jack Parlabane, to the dour Presbyterianism of Rebus – via Val McDermid’s snarky journalist, Lindsay Gordon, and the unashamed warm delight of Hamish Macbeth.

So is Tartan Noir really a genre, or just a marketing ploy to get people to read Scottish crime fiction?

Is Tartan Noir really a genre, or just a marketing ploy to get people to read Scottish crime fiction?

One thing’s for certain: whether it was Ellroy or Rankin who came up with the name, they were playing fast and loose with the term ‘noir’.

There’s been a lot of debate over the years about what constitutes ‘noir’, but it needs a lot more than a thrawn protagonist to carry it off.

It’s been described as ‘working-class tragedy’, though it’s bigger and older than that.

Shakespeare’s Othello, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet are all tragedies about powerful people, but they’re doomed from the start by their own actions or inactions. And that’s noir.

So while McIlvanney is rightly hailed as the Grandfather of Tartan Noir, the Great-grandfather must be Robert Louis Stevenson. His Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and The Body Snatcher are as Noir as a Scotsman is thrawn. Flawed protagonists doomed not by fate or outside influences, but by their own weaknesses and desires.

Most of what gets marketed as Tartan Noir is nothing like noir. That doesn’t mean they’re not enjoyable books, it just means they’ve been dressed up in someone else’s clothes.

But there are some writers out there wearing their own: Allan Guthrie, Ray Banks, and Irvine Welsh all revel in noir’s essential darkness.

I even had my own go at a proper noir tale, with Birthdays for the Dead, but mostly my noir is of the tartan variety: not so doomed, but every bit as dark.

大象传媒 Radio 4

-

![]()

Open Book: A Tartan Noir Special

The real deal

-

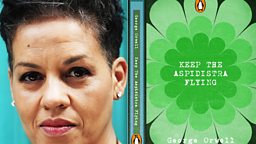

![]()

How the author transformed Scottish fiction

Welcome to #LovetoRead

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

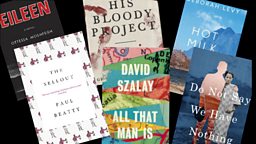

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.