Aberfan

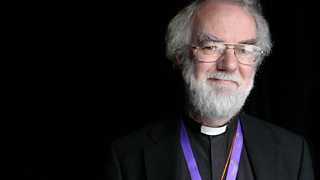

Roy Jenkins marks the 50th anniversary of the Aberfan disaster which killed 144 people, 116 of them children.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the disaster in the South Wales mining village of Aberfan which killed 144 people. 116 of the victims were children just starting their day in Pant Glas Junior School. News of the catastrophe, one of the first to be televised, sent shockwaves of grief and sorrow around the world. A generation of children were wiped out, controversy raged in the aftermath and the small tight-knit community of Aberfan would never again be the same. Roy Jenkins meets some of the people who were there at the time, and reflects on the event in the light of Christian faith. With music by the ����ý National Chorus of Wales, directed by Adrian Partington. Organist Jeffrey Howard. Producer Karen Walker.

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Script:

Please note: This script cannot exactly reflect the transmission, as it was prepared before the service was broadcast. It may include editorial notes prepared by the producer, and minor spelling and other errors that were corrected before the radio broadcast. It may contain gaps to be filled in at the time so that prayers may reflect the needs of the world, and changes may also be made at the last minute for timing reasons, or to reflect current events.

R4 Continuity:

����ý Radio 4. Now Sunday Worship which today comes from Wales and marks the 50th anniversary this week of the Aberfan disaster. With music from the ����ý National Chorus of Wales, it’s presented by the Rev’d Roy Jenkins.

ROY at MEMORIAL GARDEN

Good morning. We’re at the end of a narrow street of terraced houses, typical of mining communities across the South Wales valleys, and I’m standing in a memorial garden, simple, neat, well cared for. It’s clear shrub-filled lines trace the outline of the classrooms of Pantglas Junior School, which stood here until that terrible grey morning in October 1966 when an avalanche of colliery waste slipped down the mountainside, swept through houses, overwhelmed this school, and killed 144 people, 116 of them children.

In a region familiar with colliery tragedies, the disaster here at Aberfan represented a peculiar horror - by its scale, and more by the ages of most of its victims. It ripped the heart from this community, sparked huge controversy, and prompted practical support from around the world.

Today we hear from some of the people who were here at the time, and reflect on the event and its continuing significance in the light of Christian faith.

On Friday there’ll be a memorial service in one of the village churches, as there has been every year on the anniversary. Methodist minister the Rev Gareth Hill (himself from a mining valley), has written a commemorative hymn, set to a tune much-loved in Wales, ‘God who knows our darkest moments meets us in our brokenness.’

HYMN: God who knows our darkest moments (Dim ond Iesu)

RJ at CEMETERY

Now a prayer.

Heavenly Father, you are the giver of life.

In Jesus Christ, you have overcome death.

You stand among us in our greatest joys and our deepest sorrows.

Be with all for whom remembering remains painful, after many years;

and those who are newly pierced by grief.

In your great love, banish fear, revive faith, renew hope,

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Most of the children were buried here, high above the village, in the cemetery screened now by trees from the busy A470, the road from north to south Wales. In rows of linked arches, their individual graves are still carefully tended, inscriptions on the stones aching with poignancy: a little girl - ‘whose hopes were highest in the midst of her happiest years,’ a boy ‘who loved light, freedom and animals’

Gaynor Madgwick has come here often to remember her brother Carl and sister Marilyn. All three of them were in the school that day, but she was the only one to get out: Carl and Marilyn died in classrooms either side of her.

INSERT 1: GAYNOR MADGWICK

It was a Friday. I went into the classroom, and I sat towards the front of the classroom and then we got our little books out, y’know, with the little desks. Next thing … it was just the noise, a horrendous, horrendous rumbling … um … I can’t explain it. There was something coming. It just got louder and louder and louder. And I from the glance in my eye, looked up through the windows and I just seen black. I just managed to get up from the desk for the door, because the door was to my right hand side, and I just never made the door. Anyway, I woke up and it was just a scene of carnage. My first instinct was, because I couldn’t see my legs and I couldn’t feel my legs, I just thought my legs had gone. There was a little boy who was sat next to me who was sitting under the rubble but he was free from debris to his face, and even as a child at nine, nearly nine, you understand what death is. And we knew he had died. Um, now what happened with myself was my hand had gone tight into the crack of the wall, sealed up, and I couldn’t move my hand but from the other classroom into my classroom, there was another child’s arm but I knew there was somebody attached to that arm, in the next classroom. And I was holding onto this hand, pinching this hand, just to see if it would move. I don’t know why I done that, you know, but that gives me comfort years on thinking that might have been my brother’s hand.

ROY:

Gaynor would spend three months in hospital with serious damage to her leg. She now has children and grandchildren of her own, but in what she calls ‘a very roller-coaster life’, the events of that day have never stopped haunting her.

She does cherish many happier memories, among them the fun and games of Monday evenings at the Sunshine Corner run by the Rev Irving Penberthy at Zion Methodist Church. Twenty children from that group died in the disaster.

The recollection of that period is so painful to him, that he’s only recently felt able to speak about it.

INSERT 2: REV IRVING PENBERTHY

I realised that there were two scenes in Aberfan – the disaster scene and also the distress scene, and I stayed with the people who were waiting and watching and wondering, talking to them and trying to reassure them and then they set up Bethania as the mortuary and I went there. I, I stayed at the mortuary and went in with many of the fathers to identify their children and that was the worst – I knew many of them – and stood with them and cried with them, too, as you can imagine. Of course the little bodies were laid in the pews, covered with a blanket, and the terrible thing was you’d go around just lifting a blanket – and ‘not that one’ and of course when they did eventually find their child then … they say ‘grown men don’t cry’ but they do. That was the only thing we could do. That went on through the night, Friday night, and of course by the next morning only then did I realise the enormity of it all.

ROY:

Congregational minister the Rev Derwyn Morris Jones, a miner’s son from North Wales, was chaplain to the mayor of Merthyr Tydfil, and he shared the task of knocking on doors to find out families’ wishes for the funerals.

INSERT 3: REV DERWYN MORRIS JONES

As we visited you sort of, well, you know, you had no words – you couldn’t plan to be saying anything, you had no clever things to be saying and God forbid that we did, that we had any formula to offer. All you had was to hold people tight, to caress them, to be with them (tearful pause) but it was amazing how courageous people were face to face with, well, what was terrible for them. Terrible, of course.

HYMN: Cast thy burden on the Lord (Elijah)

RJ at BAPTIST Church

I’ve come now to Merthyr Vale Baptist Church, right opposite the site of the colliery whose waste was dumped on the mountain (and poured back down with such devastating effect).

As word spread that the tip had slipped, miners ran to the school and kept digging until they could barely stand. People clawed at the debris with bare hands, and men with shovels were turning up from across South Wales, together with skilled medical and rescue workers. Volunteers manned emergency relief centres dispensing refreshments day and night; and many in shock themselves tried to comfort grieving neighbours. Confronted with the unthinkable, people did what they could.

The minister here was the Rev Ken Hayes. He and his wife Mona lost one of their own sons, Dyfrig, who was nine - everyone else in his class was also killed, including the teacher.

Ken died nineteen years ago, but I interviewed him on a previous anniversary.

INSERT 4: REV KEN HAYES

What happened was the disaster happened on the 21st. It was the Friday 9.16 in the morning and then through the Friday and Saturday we were doing the pastoral work. We were setting up relief centres, arranging the help for various people. Houses had been destroyed. Then on the Sunday morning I took the service as normal and on the day before the disaster, I’d been asked to conduct a funeral and I still conducted that on the Tuesday – that was a non-disaster victim – And then on the Wednesday following the disaster we … um … I buried my son in the afternoon … and then we conducted a memorial service to the Sunday school scholars at nine in the evening (clears throat) and then on the um Friday I had the funeral of fourteen victims privately. I had five different funerals – we started at nine and finished at four in the afternoon. After the disaster I don’t think I went to bed for about four nights.

ROY:

People marvelled that Ken Hayes could conduct services during this time but for him it was simply the right thing to do. What was remarkable about this man was not just what he did through his grief in those first days: it was the way he stuck to the village, staying on for 25 years, becoming a natural leader, his courage and compassion rooted in a faith which was both simple and profound.

The present secretary of this church, Janet O’Regan, was sent back home to the valley from her first teaching job in London when news of the disaster broke. She reads one of the Bible passages Ken Hayes chose that weekend, from Romans chapter 8.

BIBLE reading - Baptist secretary Romans 8.35-39 RSV

Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? Shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? As it is written, ‘For thy sake we are being killed all the day long; we are regarded as sheep to be slaughtered.’

No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.

HYMN: Cradle, O Lord (Springfield: Thou Lord hast given thyself)

ROY:

Christopher Bradnock’s ‘Cradle, O Lord, in your arms everlasting.’

The horror of large-scale disaster has become all too familiar today, from war zones and terror attacks, flood, earthquake, famine: the cameras or mobile phones are there. But this was one of the first such events to be beamed (live) around the world. It raised huge questions, and provoked very different responses - as Gaynor Madgwick saw in her own family.

INSERT 5: GAYNOR MADGWICK

Faith for me has been a massive part of my life and part of my healing, my personal healing. As a family unit when we were young we always went to church on a Sunday and always went to Sunday School, sang the songs, and always enjoyed it so, for me, I had to have something that I could hold on to. That gave me a lot of comfort as a child. Sadly, my mother and father became atheists overnight and I couldn’t understand, and it still saddens me until today, that they got nothing to hold onto, my Mam and Dad, because I wanted them to believe again because for me when their time came they had to have that faith, knowing they are going to be reunited with my brother and sister. And I just found that very difficult to accept, because I wanted them to believe again. And my father was, oh God, so angry and my mother was so angry that, if there was a God, why couldn’t he actually part the sea of slurry to enable every child to get out of there safe. And I can see where she’s coming from and my father, one of his quotes was, if you went down the school that day, anyone in sound mind – and that’s my Dad’s words – would never believe in God, what he saw that day.

ROY:

Irving Penberthy faced tough questions on his first visit back to the factory where he was chaplain.

INSERT 6 REV IRVING PENBERTHY

The men, of course, said how do you explain this? I was really put on the spot in Hoover factory on the Monday morning, the next time I went. And that’s really a gruelling … I tried to say that, y’know, the National Coal Board was ultimately to blame, that’s how the people put it and this is the way of this world. That trouble and tragedy occur and that the cross is the symbol of it. There are two sides to the cross – the one is the side that reminds us that we are in a world where we are going to have trouble and violence and cruelty and it was vented on Jesus, but it is also a world where love and truth will overcome in the end, and the victory will be God’s. Roy asks: And what sort of a response did you get from those men? Silence I think. They stopped to think. Of course, I’d been in it. I don’t think they could take out their anger on me. Not at that time. Although they had their anger, but they vented it mainly on the National Coal Board, which of course ultimately was to blame.

ROY:

He confessed at the time that his faith had been shaken to the core, and Derwyn Morris Jones had his own wrestling to do.

INSERT 7: REV. DERWYN MORRIS JONES

Well yes um I trusted at the end of the day it made me a better Pastor than I could have been otherwise. And of course it shook any superficial faith that I might have had. Yes, I think that Aberfan has influenced my whole ministry and I … I’m still unhappy with theologies which are not facing life as it is and as it’s experienced by people. And the questions which people ask and the mystery which is God and … and why things should be as they are. But of course one clings to Jesus Christ. Without Jesus, God knows where we’d be - that’s the truth. … and God was in Christ. This is the centre of the Gospel, isn’t it, and in his suffering. It’s as if God himself wouldn’t have dared to approach mankind except through suffering, because men in themselves have suffered so much.

ROY:

…an echo here of the long and searing work by the distinguished poet Gwenallt, who linked the disaster with the agony of Christ.

‘He descended into depths that lie deeper than the suffering of Aberfan,

The demonic depths of mankind and the eternal depths of God.

From his wounds and from the blood of his head there flowed to us, sinners, justification, righteousness,

Forgiveness and love; and with our hands strengthened by grace we will clasp the chord that ties us to him; a chord that no disaster can sever.’

Not even the darkness of ‘the valley of the shadow of death’. There ‘I will fear no evil, for you are with me,’ affirms Psalm 23, read then as it is so frequently at times of personal and national sorrow. ‘The Lord is my shepherd I shall not want’, sung in Welsh now to a setting by Dilys Elwyn Edwards.

CHOIR: The Lord’s my shepherd (Welsh)

ROY:

Living in a very similar mining community half-a-dozen valleys away, I listened and watched appalled to the stories of survivors and rescuers. I later followed the arguments about responsibility and blame, read reports of the inquiry, seethed when the government scandalously demanded a slice of the relief fund raised by donations, in order to clear the tips (money returned only after decades of campaigning).

I heard about the traumas of those feeling guilty because they’d survived, the high sickness rates, the premature deaths of heart-broken parents.

And there were also the many dedicated attempts to rebuild - the efforts to restore some kind of childhood normality to boys and girls who’d lived through the nightmare, the community centre, clubs and groups of every kind, the new schools, the counselling service financed by the churches in Canada, the youth centre built by Britain’s Methodists, and much more.

But it was many years before I felt free to come, and then only in response to a specific invitation. I’d been terrified of intruding on an unspeakable grief, a trespasser trampling on sacred space. I would always be an outsider. This was Aberfan’s disaster.

Yet this was also an event of national significance, maybe the ugliest epitaph to a once-dominant industry. It changed the physical appearance of Wales as tip clearance helped to make the valleys green again. It taught hard lessons about industrial responsibility, about dealing with trauma, about community building, and much more. Fittingly, the book of remembrance, naming all who died, is on public display at the Senedd, home of the Welsh Assembly in Cardiff Bay.

I’ve met genuine welcome here, but I don’t regret the restraint which kept me away for decades, and was grateful that in those years, nobody asked me for words in a place where the love of God was so often mediated through human warmth.

But familiar words were used. And fifty years on I know I’d still be wanting to hear those words which were uttered with courage from pulpits and at gravesides - the 23rd Psalm, with its promise of the presence of the Good Shepherd, the assurance from the prophet Isaiah: ‘Fear not, I have called you by name, you are mine….when you pass through the waters I will be with you… the waters shall not overwhelm you.’ And the glorious conviction of Paul that no tragedy, not even death, can separate us from the love of God in Jesus Christ.

Of course many mourners are so overwhelmed at such moments that the words barely register. But it’s important that they’re spoken. They don’t deny the grief and the bleakness, but they defy it. They don’t untangle all the mysteries, answer the questions of innocent suffering, right all the injustices. But they burst with hope. They’ve sustained through the tears of many generations, and they need to be repeated.

As in many other places, there are now far fewer churches here - and while there is indeed faith outside them, congregations are smaller and older. They struggle, but they witness to the same truths, and offer the same invitation to life.

They affirm still that in the middle of the most grievous suffering, God is active for good. It’s true here, as it is where war and terror blight, where families risk death on flimsy craft to escape repression, where the most vulnerable are abused or ignored.

A century ago, Timothy Rees, who was to become Bishop of Llandaff, was a chaplain at the Somme and the agonies he saw there helped to shape his thinking about how God works in a suffering world. I love this verse:

God is love, and he enfoldeth all the world in one embrace.

With unfailing grasp he holdeth every child of every race.

And when human hearts are breaking under sorrow’s iron rod

All the sorrow, all the aching, wrings with pain the heart of God

At the heart of the pain, God is there, eager that we respond a gracious invitation to taste the divine love for ourselves. That hymn, then: God is love, let heaven adore him.

HYMN:God is love, let heaven adore him (Blaenwern)

READER at MERTHYR VALE BAPTIST CHURCH

As we come with our prayers, we give God thanks for faithfulness through the years, and remember those for whom this anniversary is hard to bear.

Gracious Father, you love us with a love that is beyond our deserving and beyond our understanding. Always you have loved us

- when our hearts have been warmed by your nearness - and when you have seemed absent, immune to our suffering, deaf to our cries;

- when we have tried hard to do what is right - and when through self-interest or weakness, we have chosen what we know to be wrong.

Always you love us, always you invite us to look for forgiveness and new beginnings in Jesus Christ.

We bless you.

Lord of love, we thank you for all who make your love visible, and pray for them:

- men and women, badly hurt, who forgive and hold no grudge;

- those who risk personal security and ambition to care for others;

- all who endure hardship to stand for justice and truth.

Grant us grace to learn from them, and to love like them.

We remember all who today need to know that they are loved:

- children: neglected, abandoned, abused;

- all who are desperate to escape the terrors of war;

- all who believe in their loneliness that no one cares whether they live or they die.

In whatever ways are within our grasp, enable us to be agents of your love;

For Jesus’ sake. Amen.

RJ at CEMETERY

At the hillside cemetery on that bleakest of mornings when most of the children were buried, numb with grief and fighting tears, the vast congregation nevertheless managed to sing a great Charles Wesley hymn of faith - to a tune by the Merthyr composer Joseph Parry. Jesu, lover of my soul.

HYMN: Jesu, lover of my soul (Aberystwyth)

Blessings at cemetery

1. Grant us faith, Lord, to trust where we cannot see; to believe when doubt overwhelms us, to take for ourselves the great promise that no tragedy, no fear, no pain, will ever be able to separate us from the love of God, which is ours in Christ Jesus our Lord.

2. And the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with us all, now and for ever. Amen.

Atmos fades to black.

CLOSING ANNO:

This morning’s Sunday Worship, marking the 50th anniversary this week of the Aberfan disaster, was presented by the Rev’d Roy Jenkins. The ����ý National Chorus of Wales, was directed by Adrian Partington, and accompanied on the organ by Jeffrey Howard. The producer was Karen Walker.

Broadcast

- Sun 16 Oct 2016 08:10����ý Radio 4