The war that had been planned was not the war that broke out. Like much of the country, broadcasters had expected Chamberlain’s declaration on 3 September 1939 to be followed swiftly by a massive attack from the air. When that failed to happen, radio listeners started to grumble loudly that the ����ý’s new emergency ‘Home Service’ was a failure. Here, newly-released material from the ����ý’s archive reveals some of the behind-the-scenes struggles to keep the British people entertained and informed in the early months.

Within minutes of the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declaring that Britain was at war with Germany, the ����ý broadcast a series of Government announcements that would transform public life at a stroke:

With cinemas and theatres shut and many people staying at home, the burden of entertaining the nation now fell squarely on the ����ý.

The British people also expected military events to move rapidly and tuned-in expecting the news to be bursting with important information.

Yet for the past nine months the ����ý had known that as soon as an emergency was declared its broadcasts would actually be severely curtailed.

The ����ý planned to be broadcasting virtually round-the-clock.

There would be lots more news bulletins in the schedule. Yet, at least to begin with, this would have to be done with fewer staff and more basic facilities. It would mean fewer talks and plays, less music, and hardly any outside broadcasts on the airwaves.

There would probably also need to be lots of ‘filler’ items, such as live organ music, to allow for the quick insertion of important announcements.

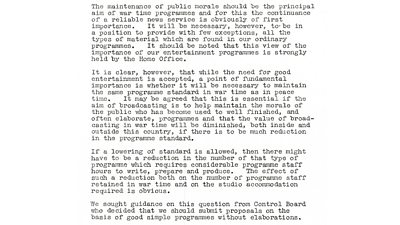

The document below - from January 1939, and marked ‘secret’ - sets out some of the constraints on ‘business-as-usual’, and reveals a ����ý fully expecting a drop in the quality of its broadcasts:

One crucial section of the document admits that ����ý programmes had an important role to play in maintaining public morale.

Yet it also went on to explain they might need to be simplified, and that those which traditionally demanded more production time and effort, such as plays or elaborate concerts, might just have to be reduced in number:

Having geared itself to a regular supply of news and filled much of the rest of the schedule with calming and largely anodyne fare, the absence of a sudden and large-scale aerial bombardment when war finally was declared in September 1939 left the ����ý’s output sounding distinctly ‘stale, makeshift, and inappropriate in mood and content’.

Indeed, as the historian Siân Nicholas puts it, ‘the first weeks of the war were a disaster for the ����ý’.

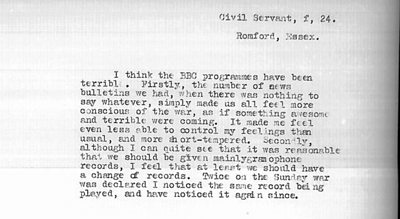

This, for instance, is the brutal first judgement of one listener in Essex, as captured by Mass Observation:

There was one area of programming which responded quickly and sensitively to the changed circumstances - simply by offering continuity.

On the eve of the war, hundreds of thousands of children had been evacuated from the big cities and towns. They were often separated from class-mates and siblings as well as their parents.

The ����ý’s regular Children’s Hour saw an opportunity to serve this scattered audience.

One of its producers at the time was David Davis, and in this extract from his oral history interview he recalls what happened:

The Government considered the ����ý’s most important function in wartime was to be a conduit for official information and advice.

In the coming months, it launched countless campaigns on war-savings, air-raid safety, ‘Digging for Victory’, fuel economy, food rationing, and recruitment to emergency services, all of which demanded airtime.

Some of this was tolerable. Indeed, home cooking programmes such as The Kitchen in Wartime, What Shall We Have Today? and Feed the Brute - featuring the comedy duo ‘Gert and Daisy’ - proved immensely popular with listeners. But the ����ý faced constant pressure from ministers eager to talk before the microphone themselves, and constant interference from a range of ministries over the content and style of scripts.

The ����ý knew from experience that ‘messages’ had to be deployed in subtle and entertaining ways; the results when Government and its civil servants had their way were altogether clumsier.

To some extent, the ����ý was paying an inevitable price for the close relationship it had built-up over the years with the governing class.

This comes across clearly in an archive interview with John Green, who produced some of the ����ý’s wartime farming programmes. In it, he reveals not just the wartime unity of purpose between Government and Corporation, but the social connections between Broadcasting House and Whitehall. In particular, he explains how his wartime farming programmes had their origin in an approach to the ����ý from the President of the Farmers Union:

It’s not hard to imagine the rather dry, ‘official’ style of many of the programmes John Green went on to make. Even so, the ����ý’s sometimes stodgy output was only one factor in shaping public mood.

The cinemas and theatres had now re-opened but there was a nervy sense of stasis at large - a sense of waiting for something big to happen, only punctuated by news of endless German military success.

The first winter of the war was especially harsh. And there were the ‘petty annoyances’ of rationing and the blackout to be endured.

This broader mood was captured by the investigators of , who monitored public opinion throughout the war by gathering-up responses to questionnaires and hundreds of diaries being written around the country.

The ����ý itself featured one of the Mass Observation diarists - a bank clerk, reading his own entry for 28 March 1940:

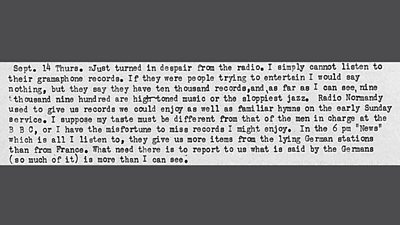

In Sussex, another Mass Observation diarist, Adelaide Poole, regularly vented her own irritation with the ����ý.

On 14 September 1939, as was often the case, it was the ����ý’s choice of music that caused offence:

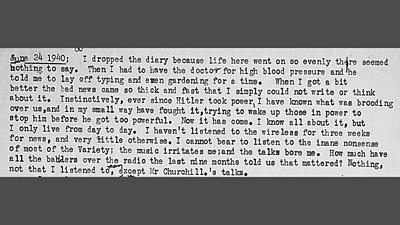

And a few months later, on 24 June 1940, she was cross with almost everything she heard:

In truth, the ����ý’s greatest programme failures were in the very earliest days and weeks of the war.

Even before the close of 1939, the number of news bulletins had been reduced, outside broadcasts had returned, and some big popular entertainment shows were back on the airwaves: Band Waggon, ITMA, Songs from the Show.

The ����ý was also managing to find some new ‘stars’, even when it came to pep talks on rationing or health. One of the most surprising of these was the ‘Radio Doctor’, Charles Hill, who many years later became a controversial Chairman of the ����ý.

In this interview from the ����ý Oral History Collection, Hill reveals how his career on air began, and how he evolved his own, highly spontaneous style:

The single most significant factor inhibiting the ����ý’s freedom to broadcast whatever it wanted - and however it wanted - was political.

The Committee of Imperial Defence had decided back in 1935 that, in the event of war, the Government would assume 'effective control of broadcasting and the ����ý'.

A wartime Ministry of Information would have the right to censor all output in the interests of national security, and the Government would have the right to direct the ����ý in all matters related to the war effort.

A document dated 29 June 1939 set out some of the likely implications of this control for the ����ý’s News Department:

Once war began, relations between ����ý and Government became more nuanced than these formal arrangements suggested.

The censorship process was set out in the strictest terms: every script needed a ‘stamp’ from an official censor before it could be used, and in every studio a ‘switch censor’ would sit-in to turn down a microphone if anyone deviated from what had been agreed.

But day-to-day, much censorship was devolved to senior and mid-level ����ý staff, some of whom were seconded to the Ministry of Information: in practice, the ����ý was often left to censor itself. And those charged with this responsibility were often capable of approaching their task uncomplainingly - as we can hear in this archive interview with Alec Sutherland, who was then working at Broadcasting House in 'Recorded Programmes':

In his interview, Sutherland also reveals one particular type of wartime censorship which has been neglected in official accounts of the ����ý - its treatment of Big Ben:

Sutherland gives us a portrait of censorship at its most benign and co-operative. Yet there was often friction between the ����ý and the Government, especially in the early part of the war.

The ����ý itself had no objection to being a supporter of the British cause, an exhorter, a morale-builder. But it claimed that ‘propaganda, in the sense of the perversion of the truth’ was not ‘in accordance with ����ý policy’.

Its Home Service News Editor, R.T. Clark, expressed the Corporation’s underlying thinking:

the only way to strengthen the morale of the people whose morale is worth strengthening is to tell them the truth and nothing but the truth, even if the truth is horrible.

Government ministries and senior military personnel, however, often limited the supply of accurate information reaching the ����ý.

One example of this was in May 1940, when the ����ý was tricked into misleading listeners over Winston Churchill’s inept attempt to secure the ports of neutral Norway before Germany did.

One of the ����ý’s wartime Governors, CHG Millis, gives an insider’s account of the event, for the first time, in this oral history interview:

Millis stresses the ����ý’s formal 'independence' from Government. But he only tells half the story. The ����ý was actually given a communique from the War Office and the Admiralty which stated boldly - and inaccurately - that the British had successfully captured the port of Narvik. Its news bulletin then reported this on air in good faith.

Just over a week later, Allied forces in Norway were being evacuated. It revealed just how overinflated the official account had been. The Press was misled just as much as the ����ý in this instance, but the Corporation’s reputation for truthfulness was dented.

Unsurprisingly, a Mass Observation survey revealed that a ‘peak of disbelief in the news was reached during the Norwegian campaign’.

By the end of May 1940, it reported, that ‘many women were deliberately refraining from listening to the wireless, and said they preferred not to think about it.’

There is a striking reminder, too, in the Mass Observation Archive, of just how sceptical and disengaged listeners were in general at this stage of the war.

The organisation had asked people to observe wireless listening in their local pubs and cafes.

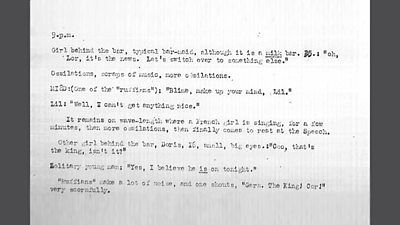

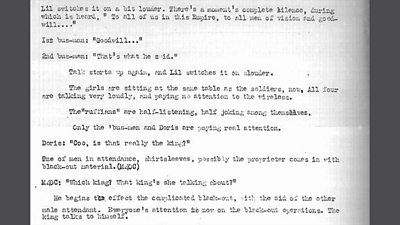

One colourful reply eavesdrops on Charlie’s Snack-Bar in Romford, where the radio-set was turned-on when a speech from the King came on the air:

Despite censorship, the ����ý’s broadcasts did not remain the same throughout the war. Even during the ‘Bore War’, there were signs of a livelier style returning, of a ����ý more confident in capturing the experiences and sounds of the people of Britain, as much as the opinions and advice of their leaders.

In this newly-released interview from the ����ý Oral History Collection, George Budden, a mobile recording engineer based in Manchester, describes the extraordinary range of assignments he was soon being given:

By the summer of 1940, France and the Low Countries had been occupied by the Nazis, and the war was coming to Britain, with increasing numbers of air attacks on airfields across the south.

The ����ý’s response was increasingly agile. It had recruited more journalists and engineers. It had access to more - and better - recording equipment. It was able to cover the ‘Battle of Britain’ by sending its own reporters to the coast in specially equipped cars.

One of the most famous accounts brought back - of an aerial dogfight between RAF planes and the Luftwaffe - was recorded near Dover by Charles Gardener:

There were plenty of people - both inside the ����ý and out - who thought Gardener’s jaunty style horribly inappropriate. But it had the virtue of being spontaneous and human.

As the historian Siân Nicholas has written, the ����ý ‘had weathered rather than triumphed’ in the so-called ‘Bore War’. But there were signs of it learning from its experience, and of a more confident approach emerging to wartime broadcasting.

This came just in time, for by the autumn of 1940, the war was to enter a new and deadly phase, with the arrival of the ‘Blitz’.

Further Reading:

- Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004)

- Siân Nicholas, The Echo of War: Home Front Propaganda and the Wartime ����ý, 1939-45 (1996)

- Dorothy Sheridan (ed.), Wartime Women: A Mass Observation Anthology 1937-45 (2000)

- Daniel Todman, Britain’s War: Into Battle 1937-1941 (2016)