The ����ý saw one of its main wartime missions as nurturing civilian morale in the country at large. But what sort of radio lifted the spirits for those listening at home or in the workplace? Programmes of information or of escapism? Talk or music? What sort of radio lifted the spirits for those listening at home in wartime? Here, newly-released archives show how the ����ý sought to measure – and influence – the public mood.

The Government and the ����ý’s most senior administrators were at one on the role the ����ý had in mobilising the civilian war effort. But this was a mission which never needed to be imposed from above.

Throughout the Corporation’s hierarchy, producers, engineers, scriptwriters, announcers – radicals and conservatives alike – recognised the virtue of using whatever skills they had to fight fascism.

One of the ����ý’s most famous wartime announcers, John Snagge, had no doubt in his own mind what exactly this meant for ordinary programme-makers:

The ends were clear, then: to make programmes that nurtured public morale on the Home Front. The means of doing so were a little harder to define.

Snagge himself stressed the need to 'take people away from thinking about the war'. And in this respect, comedy was perhaps the most obvious weapon in the ����ý’s armoury.

One of its most popular wartime series was It’s That Man Again – or, as it was better known, ITMA:

ITMA had been launched in the summer of 1939 to a tepid reaction. Indeed, the series was almost cancelled. By 1944, however, nearly 40 per cent of the population was listening every week.

The writer, Ted Kavanagh, realised that its storylines were tenuous; it was the procession of regular characters, each with their own catch-phrases that mattered - Mrs Mopp ("Can I do you now, sir"), Colonel Chinstrap ("I don’t mind if I do"), and the rest, all in orbit around the star at its centre, Tommy Handley.

The war was an important backdrop throughout. And, as John Snagge recalls in this extract from his archive interview, ITMA thrived – despite Handley’s own rather complicated personality - thanks to the series’ quick-fire lampooning of all the seemingly petty regulations of the time: ministry announcements, rationing, restrictions, careless talk:

Snagge talks of ITMA pulling legs, but ‘never brutally’. It provided what the historian Siân Nicholas calls ‘a common reference point and a common vocabulary’ for its millions of fans.

Listeners enjoyed the chance to share punchlines in the street, to be a little bit rebellious. The ����ý had the chance to show it was by no means simply a mouthpiece of officialdom – that it was in tune with popular sentiment.

ITMA was produced by the ����ý’s Variety department, which had been relocated to Bristol at the start of the war. When the bombing there became too intense, it relocated again, this time to Bangor in North Wales.

Listeners were entirely unaware that many of their favourite episodes were broadcast from the coastal town. And the team behind the show also hoped they would no longer be in the Luftwaffe’s sights. However, as one interview in the ����ý Oral History Collection shows, this was not always the case.

The interview is with John Ammonds, who created many of ITMA’s comic sound effects:

The popularity of programmes such as ITMA was a useful reminder to the ����ý of the need for plenty of entertainment in its schedules. But there would have to be news, too – and a good deal of it.

The ����ý had decided at the outset that the ‘principal objects of wartime broadcasting’ were ‘the maintenance of public morale’ and being ‘the vehicle for official announcements and the radiation of reliable news’. Were the two aims incompatible? Or might news itself be a crucial factor in strengthening public morale?

This was the sort of question which fascinated Tom Harrison and his team of investigators at Mass Observation. In 1941, Harrison was recorded speaking about the significance of their wartime work:

What, then, did all Mass Observation’s personal accounts reveal? It would be foolish to generalise from such a large and varied collection. But it certainly offers evidence of people’s heightened sensitivity during the war to ‘the News’ – good or bad.

Here, for instance is one woman’s diary entry for 9 April 1940, in the midst of the Norwegian campaign:

I felt so nervy and jumpy after tea – could not settle – I kept turning the wireless to see if there was a news bulletin anywhere in English – not German – and wondering if our sailors were winning in the reported sea battle.

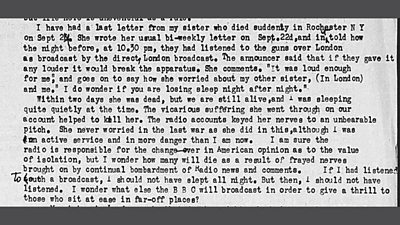

And here, by way of stark contrast, is Adelaide Poole, a diarist in Sussex, who avoided listening to the news at all, because she believed it was responsible for the premature death of her own sister in the United States:

This particular diarist was averse to news in general. But, a succession of bad news was always a turn-off.

In her diary entry for 17 February 1942, she reveals a particular aversion to politicians who made speeches without being able to bring her anything of 'cheer':

Yet it was clearly sometimes possible for broadcasting to report bad news truthfully while somehow lifting the national spirit at one and the same time.

The classic example was J.B. Priestley’s talk – his first - in the Postscript to the News series on Wednesday 5 June 1940.

Dunkirk had just been evacuated – the climax to an obvious military catastrophe that might easily have become a national humiliation.

Perfectly-timed to shape public perception before it had settled, Priestley’s talk that night was a masterclass in the art of subtle persuasion:

Priestley’s talk of the ‘little holiday steamers’ and of ‘snatching glory out of defeat’ helped cement in the national psyche a powerful myth of British pluck and ingenuity outmanoeuvring the Nazi’s soulless war machine.

Churchill might speak powerfully of ‘the nation’, but it was Priestley who spoke more eloquently of ‘the people’.

It was a great script. But Priestley’s mellow Yorkshire tones and down-to-earth style mattered just as much. Indeed, as this archive interview with the ����ý’s war correspondent, Godfrey Talbot shows, broadcasters were acutely aware of how important the personality – and, in particular, the voice - of the presenter was in guaranteeing a programme’s success:

What, then, about the small team of ����ý announcers, who introduced every programme and read every news bulletin?

It had long been a matter of principle at the ����ý that they should speak in detached and neutral tones. In wartime, there was the added need to avoid sounding remotely bombastic: that, after all, was very much the Nazi style.

These announcers were now named on air – an emergency measure designed to avoid the risk of impersonation.

So, did that mean they were becoming celebrities? Not according to one of their most prominent members, John Snagge:

Snagge very much reflects the official line: that public trust in ����ý news depended in part on the maintenance of the announcer's 'unemotional' delivery.

The public sometimes had different ideas. In her diary entry for 29 November 1939, Adelaide Poole detects a hint of emotion at the microphone – and embraces it:

Perhaps, then, even among the Praetorian Guard of ����ý announcers, there was room for an audible hint of humanity.

Indeed, in this archive interview with Alec Sutherland, from the Recorded Programmes department, there’s evidence that, even within the confines of their allotted task, the announcers competed with each other to impress their personalities on the listening public:

The maintenance of morale was not just an issue of reaching the listener at home. In wartime, there were thousands of men and women working in civilian defence bases, such as anti-aircraft batteries – and many millions more working in factories.

If the war-effort was to stay on track – and, in particular, the flow of armaments kept up – they, too, needed cheering-up. They already had plenty of ‘Factory Front’ propaganda from the Government – exhortations to work harder at the production-line. So much of it, indeed, that familiarity bred contempt.

Programmes such as Workers’ Playtime took a different approach, broadcasting uncomplicated live entertainment from factory canteens around the country:

The first edition of Workers’ Playtime in 1941 was introduced by the Minister of Labour, Ernest Bevin. It was a series, he told listeners, that ‘makes us all feel that we are working together in the common cause to win this war.’

That’s certainly what a significant proportion of the British population must have felt, too, for by the following year 7 million were tuning-in regularly, many of them from home.

A more radical experiment had been launched by the ����ý in June 1940. Music While You Work was to be a programme of non-stop music specially designed for those on the production-lines.

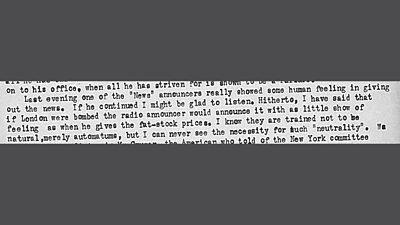

The initial idea was set-out in this memo held in the ����ý’s written archives:

By September, it had acquired its own signature-tune, Eric Coates’ quick-march 'Calling All Workers':

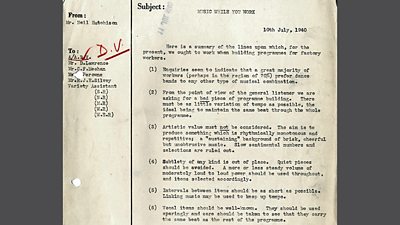

The idea of Music While You Work was simple enough: non-stop music of a steady, upbeat rhythmical kind, which would form an agreeable backdrop to repetitive work. Even if it did not increase productivity, it should certainly not decrease it. And with any luck, it might relieve the inevitable boredom.

The problem was that this approach went against all the familiar principles of ‘good’ broadcasting at the ����ý. Programme-makers and musicians had been drilled for years that what mattered was creating radio with plenty of personality, and lots of changes of tempo and mood.

Music While You Work was a team effort, coming from different parts of the country at different times – with a constantly changing rota of producers and band-leaders. In the first few months almost all of them neglected – or simply refused – to keep things simple. This caused immense irritation for those responsible for overseeing it.

Below, is a memo from July 1940 in which we see just how much the ����ý was struggling to instill the basic principles of Music While You Work, namely that it should always offer music that was ‘unobtrusive’, ‘monotonous’, yet always ‘cheerful’ – and ignore ‘subtlety’ and ‘artistic value’.

It was an ongoing struggle to weed out small-talk, slow sentimental tunes, and vocals. But by the end of the war, some 9,000 large-factories, another 30-40,000 smaller factories and workshops, and somewhere between 10 and 20 per cent of the rest of the population, were tuning-in.

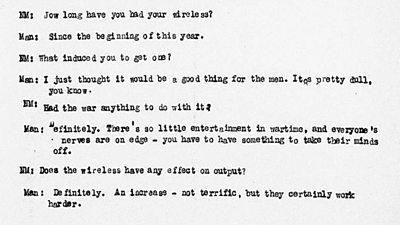

Mass Observation managed to capture some sense of why the programme proved such a hit.

Here, for instance, are the words of a factory-owner in Stepney, revealing how important it was to have background music for his staff:

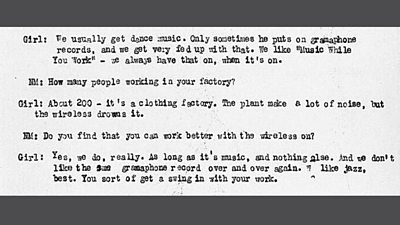

The owner doesn’t pick out any particular kind of radio programme or music. But one of the young women on his production-line has more definite views:

The ����ý was constantly monitoring such views itself. And the document below, which can be downloaded in full, represents a comprehensive analysis of Music While You Work’s first year on air.

It also represents the views of Wynford Reynolds, a new producer drafted-in in 1941, who clearly tightened-up procedures and brought extra energy to the series:

Music While You Work contradicted all the ����ý’s own deeply-held artistic instincts, just as ITMA had poked fun at the kind of bureaucracy with which the ����ý habitually engaged.

Programmes such as these were a measure, not just of how committed the Corporation was to the national war effort, but of how comfortable it could be when it allowed itself to be in harmony with popular attitudes.

War was changing the ����ý in subtle but profound ways. And in his interview for the ����ý Oral History Collection, the war correspondent Frank Gillard, spoke of how important this was to someone like him, coming in from the outside:

Further reading:

- Angus Calder, The Myth of the Blitz (1991)

- Siân Nicholas, The Echo of War: Home Front Propaganda and the Wartime ����ý, 1939-45 (1996).

- Dorothy Sheridan (ed.), Wartime Women: A Mass Observation Anthology 1937-45 (2000).