On 6 June 1944, it was from the ����ý that the world learned that D-Day was finally happening. Special broadcasts allowed listeners to follow the opening moments of the long-awaited ‘Second Front’. They showed the ����ý’s whole approach to reporting the war had been revolutionized. Here, material from the archives and the ����ý Oral History Collection take us behind-the-scenes of the day’s events, and reveals the months of preparations the ����ý had been making in secret.

The first official announcement of the Normandy beach landings was broadcast on the ����ý at 09.32 on Tuesday 6 June 1944. The announcer was John Snagge:

The war had entered a dramatic new phase. And so too had the ����ý’s news coverage. As far back as 1942 it had been agreed by senior editors that the Corporation’s ability to report from the battlefield was falling far behind the Americans, or indeed the Germans.

There had been some striking examples of the kind of vivid, location-reporting that could be done, if the ����ý had portable recording equipment in the right place and a bit of co-operation from the armed forces.

In September 1943, for instance, Wynford Vaughan Thomas had been with the RAF on a bombing raid over Berlin, and returned with a gripping commentary - full of the ‘actuality’ sounds of the aircraft and its crew, and punctuated by the reporter’s own description of the bombs dropping and anti-aircraft flak being aimed at the plane from enemy positions below:

The ����ý wanted to broadcast more of this kind of news reporting: first-hand, up-to-date, immersive – in short, reporting that took the microphone into the midst of the battle.

But Wynford Vaughan Thomas’s flight over Berlin had taken a lot of preparation and negotiation. In the recent North African campaign, the ����ý had struggled to achieve anything like the same results.

One of its reporters there was the recently-recruited Frank Gillard. But he was only despatched to the desert after the ����ý’s previous reporter, Richard Dimbleby, had been forced to return to Britain.

As Gillard explains in this extract from his oral history interview, Dimbleby had been spending most of his time based in Cairo rather than at the frontline. As a result, he’d become the unwitting victim of misleading military briefings:

The ����ý was soon thinking hard about how it could make sure all its reporting followed this ‘eye-witness’ approach. As one internal report put it, coverage from the front needed to be ‘wider, speedier, and more intensive’. And with the opening of a Second Front thought to be imminent, it set about planning how this might be achieved even in the largest and most complex of military operations.

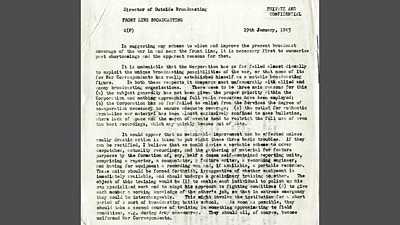

The document below, from January 1943, is held in the ����ý’s written archives. It comes from the ����ý’s director of outside broadcasting, and he makes a passionate plea for more resources, more co-operation from the armed services, and more room in the ����ý’s schedules for ‘authentic front-line material’ to be broadcast:

The next-step was the creation of a fully-equipped, properly co-ordinated ‘Radio Commando Unit’ capable of working side-by-side with military personnel.

The concept was tested in March 1943 when ����ý reporters, engineers and feature-writers took part in one of the British army’s mock-exercises, ‘Operation Spartan’.

Richard Dimbleby was among those who took part, and was asked by the ����ý to produce a frank assessment of what happened. His confidential report is below, and can be downloaded in full.

Dimbleby was critical of several aspects of the ����ý’s efforts in Operation Spartan – including the way in which the young recording engineer he had been allocated ‘wore his field cap at a rakish angle’ throughout the day. But his overall conclusion was that ‘the idea of a team in the field has been found workable’. Government officials and senior military figures were also impressed with the dummy news reports Dimbleby and the others had produced.

Soon after, the ����ý’s new ‘War Reporting Unit’ was created. The well-known commentator, Howard Marshall was put in charge.

However, Malcolm Frost, who had been switching back and forth between the ����ý and MI5 since setting-up the Monitoring Unit in 1939, was the man appointed the Unit’s new deputy. As such, it was he who did all the heavy-lifting at the beginning, particularly when it came to planning for the D-Day invasion itself – something which involved secret negotiations throughout the early months of 1944 with General Eisenhower’s team at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, as well as endless arguments with American reporters who wanted to take a very different approach to covering the landings:

It would not be possible for the ����ý’s war correspondents to have with them their own transmitters for sending reports back to London – at least, not for the very first landings. But new portable ‘midget’ recorders were being developed by ����ý engineers which would allow them to make their own recordings in the field.

Once Frost knew the broad outlines of Eisenhower’s plan, the ����ý was able to put in place a network of transmitters around the south coast, which would allow correspondents coming back across the channel to send their field recordings swiftly on to London.

By the end of May 1944, all that remained to be done was to get the ����ý’s war correspondents embedded with the military units to which they had been allocated and in position for D-Day itself.

All this, of course, had to be done in conditions of the utmost secrecy. But in the Berkshire village of Pangbourne, a young clerk for the ����ý’s Monitoring Service, Susan Ritchie, was billeted in a hostel which suddenly started filling-up with new arrivals:

On Sunday 4 June, final preparations were being made at Broadcasting House for announcing to the world that D-Day was beginning.

The ����ý announcer John Snagge was now right at the centre of events. And confidentiality was vital. So tightly co-ordinated were the broadcasters and the military by this stage, that revealing the ����ý’s plans would, in effect, have revealed the invasion plan itself.

In his oral history interview, Snagge offers a fascinating eye-witness account of the measures being taken behind-the-scenes to ensure that nothing was leaked in advance and that when the moment came, nothing would go wrong technically at the broadcasting end of the operation:

So, what exactly did the ����ý’s senior official, Benjie Nicholls, do next with Snagge’s highly confidential plan? We have an answer, thanks to another interview in the ����ý Oral History Collection, this time with Mary Lewis, who worked in a senior, and trusted position at the ����ý’s Duplicating Section:

Soon after Mary Lewis had run off copies of the ����ý’s plans for D-Day, John Snagge was escorted out of his guarded room at Broadcasting House. Along with the American reporter Ed Murrow, and a senior news official at the ����ý, who co-ordinated relations with the , Snagge was taken to another, even more heavily guarded room, at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force building in central London:

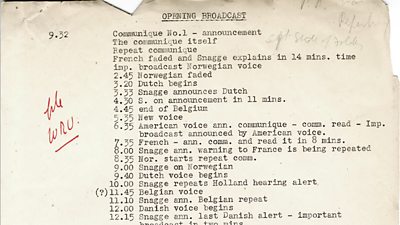

The ‘alerting period’ which Snagge had successfully co-ordinated ensured that the communique he read out at 09.32 was sent out on all the ����ý’s transmitters simultaneously.

A few moments later, the ����ý put out a stream of other messages and announcements: translations of the communique, messages to listeners in occupied Europe, a formal announcement from Eisenhower himself, recorded messages from politicians, and a promise that the King would speak to the nation at 9 o’clock that evening.

The running order of what was called the ‘Opening Broadcast’ is kept in the ����ý’s written archives:

By now, most of the ����ý’s war correspondents had already arrived in the combat zone: several, including Richard Dimbleby, had flown over the channel in bombers or fighter aircraft; seven were aboard various ships and landing craft; another three, including the head of the War Reporting Unit, Howard Marshall, were embedded with armoured divisions now fighting on the beaches; Chester Wilmot had arrived by glider; Guy Byam had parachuted into Normandy. But the first eye-witness account to be broadcast came at 13.00.

It was from William Helmore, an Air Commodore aboard a Mitchell bomber, who had been able to make a recording as he flew over the Normandy coast at ‘H-Hour’ earlier that morning:

By the evening of this first day, more and more reports had started flooding back from different parts of the battlefield, ready for the ����ý to broadcast them to an audience now desperate for the latest news.

Mary Lewis had been printing scripts non-stop in the Duplicating Section for over 18 hours when she went to the basement canteen for a well-deserved break. But she had only just arrived when one of the Correspondents still in Broadcasting House, Robert Reid, went up to her and asked if she would come quickly to the first-floor office where he had set-up a dedicated duplicating machine for the War Reporting Unit.

Lewis explains what happened next:

The bottleneck in the ����ý’s duplicating service that night was irritating proof of welcome news: that over 18-months of detailed planning had paid off. The War Reporting Unit was now supplying the ‘wider, speedier, and more intensive’ coverage the ����ý had long sought.

All that was left now was for all this rich front-line material arriving behind-the-scenes at Broadcasting House to be given its due on the airwaves.

Not long after 21.00 that evening, the Home Service launched a new programme specifically designed to do just that.

It was called . And the story of its launch is discussed in the next section of this website.

Further reading:

- Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Volume III: The War of Words 1939-1945 (1995).

- Desmond Hawkins (ed.), War Report: ����ý Dispatches from the Front Line 1944-1945 (1994).