For most of the war, the ����ý broadcast to the men and women of the armed services: the Forces Programme, the General Forces Programme, and, after D-Day, the less-well-known Allied Expeditionary Force Programme, or AEFP. They all presented challenges for the broadcasters. And as the archives reveal, the AEFP in particular provoked stormy rows between the ����ý and American military commanders.

After it launched in January 1940, the ����ý’s Forces Programme was a big success – with civilian listeners as well as the armed services. It was designed originally to boost the morale of bored British troops stationed in France and at home, and its schedule contained plenty of variety, sports news, advice programmes and, above all, light music, all woven together with a strikingly informal presentation style – the kind of radio which could be appreciated as background noise in the communal listening-conditions of barracks and mess rooms.

But the ����ý knew that the civilian population might also enjoy an alternative to the Home Service. And it therefore came as no surprise to discover that by 1942 it was being listened to by a majority of Britons. As Mass Observation reported, it offered everyone ‘a sort of tap listening, available all day as a mental background and relief.’

There was a vocal minority who wanted more news, a few more talks and discussion programmes. And the ����ý’s own researchers found that among the British Expeditionary Force there was satisfaction but little enthusiasm. But in February 1944 everything changed anyway.

The ����ý’s new Director-General William Haley had decided after a visit to British troops in Italy that what they wanted was a clearer link with home. It was decided to scrap the Forces Programme and turn the ����ý’s General Overseas Service into the alternative, for home listeners and for forces serving anywhere overseas. This quickly evolved into a merged ‘General Forces Programme’.

The head of this new service was Norman Collins, who’d already had extensive dealings with troops in various combat zones. In his interview for the ����ý Oral History Collection, Collins admits to having doubts about the Programme right from the start:

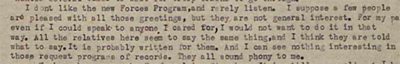

If the evidence of Mass Observation is anything to go by, Collins’ instincts were probably right, namely that the General Forces Programme was facing in too many directions at once. Here, for instance, is the diary entry for 2 April 1944 supplied to Mass Observation by Adelaide Poole in Sussex:

After D-Day, there were new opportunities for the ����ý to supply a specially-tailored radio service to the armed forces. There were also new and potentially more explosive challenges.

In anticipation of the opening of a ‘Second Front’, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had been established in the autumn of 1943, with General Eisenhower in ultimate command.

SHAEF wanted a completely new broadcasting service that would accompany the hundreds of thousands of mostly American, British and Canadian troops as they pushed inland from Normandy. And it turned to the ����ý for technical and editorial assistance.

One of those who was soon involved in making programmes for the AEF Programme was Cecil Madden, who’d been running the ����ý’s Empire Variety Unit:

Madden’s enthusiasm is striking. But he gives us a misleadingly optimistic account.

In reality, there were profound and frequent disagreements behind-the-scenes over the new service: about whether or not the ����ý was obliged to follow directives from the American psychological warfare teams based at SHAEF, as well as Britain’s own Political Warfare Executive, and – even more often – about whether the mix of programmes on offer was simply too British for the American troops.

Indeed sometimes, as even Cecil Madden admitted, the disputes descended into farce:

British and American disagreements were mostly played-out at the most senior level in London. But in this oral history interview, the ����ý’s war correspondent Robin Duff, who was embedded with American forces for the Normandy landings, points to some of the petty niggles and rivalries that reporters like him had to deal with in the field of combat:

Duff mentions the American General, Omar Bradley. And there is further evidence of the difficulties he created for the ����ý’s reporters covering Operation Overlord during the summer months of 1944.

The document shown below, from the ����ý’s written archives, is a confidential memo sent by Richard Dimbleby to a senior ����ý official back in London.

It passes on information received from one of Dimbleby’s fellow-reporters, Robert Dunnett: that General Bradley had accused the ����ý of costing the lives of American soldiers through its over-zealous reporting of events at The Battle of the Falaise Pocket:

Bradley had made a serious allegation. It was also unfair: as the ����ý now protested at the very highest levels, it had merely reported information that had been issued by SHAEF itself.

Within a fortnight, SHAEF’s chief press censor confirmed that ‘clearly the error was one by censorship here and the ����ý is entirely without fault’.

The ����ý continued to object: what would make the difference, it argued forcefully, was a public withdrawal of the allegation by General Bradley. It was not forthcoming – and indeed more complaints from the American Army followed, implying that the ����ý’s reporters were playing fast-and-loose with the rules of censorship, or exaggerating British achievements, and that as a consequence US soldiers constantly ‘jeered’ when they heard the news bulletins put out over the AEF Programme.

Considerable staff time was expended smoothing-over such disputes. By this stage, Malcolm Frost, who had previously set up the ����ý’s Monitoring Service, worked for MI5 and planned the ����ý’s deployment of reporters for D-Day, was working closely with General Eisenhower himself, providing top-level liaison between SHAEF and the ����ý.

It allowed him to clear up many of the misunderstandings. It was also a position which gave him intimate access to Eisenhower – and the chance for some extraordinary insights into the future US President’s character and political views:

There was one other lasting legacy of the ����ý’s programmes for the Forces: the creation soon after the war had ended of the Light Programme.

The ����ý’s Director-General made the obvious choice for its head, when he invited Norman Collins, who had run the General Forces Programme, to take on the role.

Yet as Collins makes clear in this last extract from his oral history interview, he himself wanted to avoid repeating the mistakes – as he saw them – of the wartime service for the troops, and build something genuinely new instead:

Further reading:

- Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Volume III: The War of Words 1939-1945 (1995)

- Maurice Gorham, Sound and Fury (1948).

- Siân Nicholas, The Echo of War: Home Front Propaganda and the Wartime ����ý, 1939-45 (1996).