The ����ý’s wartime broadcasting accorded star status to a small group of men and women who turned out to be exceptional performers before the microphone. But what were they like off-air? Newly-released oral history interviews provide some intimate snapshots, and shatter some iconic reputations.

The General, and later President of France, Charles de Gaulle, once described Tuesday 18 June 1940 as the start of his ‘new life’.

France had fallen, and the military commander had just arrived in London post-haste from Bordeaux. Now, in exile, he entered the ����ý’s studios and sat before the microphone to broadcast to his fellow countrymen and women a fierce repudiation of Pétain’s armistice agreement with Nazi Germany.

‘As the irrevocable words flew out upon their way’, he recalled, I felt within myself a life coming to an end’. Broadcasting, he said, had provided him with ‘a powerful means of war’.

De Gaulle would broadcast from the ����ý studios on several more occasions. But for him, the people of France, and for the ����ý, this first broadcast represented a dramatic and vivid moment in the war.

It had all happened so fast there had been no time to translate what he had to say for British listeners who caught his message:

There are several accounts from the ����ý’s archives of people who were in Broadcasting House that evening and met De Gaulle and his entourage. There are yet more accounts from those who met the general on later occasions.

They allow us to piece-together a clearer picture of what happened when he first arrived, and how much he divided opinion among broadcasters.

The first is from Robin Duff, a reporter of aristocratic background who would become one of the ����ý’s best-known war correspondents when he covered the liberation of Paris in 1944:

It is possible Duff is remembering De Gaulle’s second ����ý broadcast, on Wednesday 19 June, or perhaps his third on the following Saturday, since we know from other accounts that when De Gaulle made his debut at the microphone on the 18th, he was escorted to the studio by two members of the ����ý’s European Service: Elisabeth Barker and Leonard Miall.

In this archive recording, Barker is being interviewed by Miall, and takes us through a sequence of events that involved some high-level political wrangling and an outburst of bad temper:

This interview makes clear that the archive recording of that famous speech of June 1940 is, in fact, from De Gaulle’s third broadcast, not his first. In its description of that angry outburst in the Director-General’s office, it also reveals something of the general’s difficult character.

And there is another, much briefer account of De Gaulle’s behaviour inside Broadcasting House which also suggests at least some broadcasters were less enamoured of him than those tuning-in at home.

This is from Alec Sutherland, from the Recorded Programmes department:

Another personality well-liked by the public – and well-regarded by most ����ý insiders – was J.B. Priestley, whose Postscript talks became a sensation.

In the years immediately preceding the war, he had collaborated briefly with the television producer Cecil Madden. ‘He was quite delightful’, Madden recalled. ‘He used to come up and have tea at my desk, and he would make suggestions... We did something like seventeen Priestley plays, so we had a great deal of co-operation.’

But in the stressful conditions of the Blitz – at a time when a willingness to ‘muck in’ and ‘make do’ was particularly valued – Priestley evidently fell short.

In her oral history recording for ����ý Archives, Clare Lawson Dick recalls coming across the writer during one of her night-time stays in the basement of Broadcasting House:

Priestley already saw himself as a figure of ‘importance’ well before he got to the ����ý microphone. Others were made into celebrities by radio.

The singer Petula Clark was a young child when she made her debut on the wartime ����ý. And in this account, it’s clear that her ‘discovery’ was almost accidental. It comes from Cecil Madden, who by this stage was running the ����ý’s ‘Empire Variety Unit’, which made live entertainment shows for broadcasting overseas:

Perhaps the most iconic radio performer of all in wartime was Winston Churchill. But a great deal of mythology surrounds his broadcasts.

They were fewer in number than people remember; and some of those which have since become part of the folklore of the Second World War were in fact not spoken by Churchill himself at the ����ý microphone but verbatim reports of his speeches in Parliament.

Indeed, in both his dealings with the ����ý and his reception among British listeners we find a chequered, even tempestuous relationship.

Some of the popular attitudes towards Churchill were captured by Mass Observation.

This, for instance, is Adelaide Poole’s diary entry for 24 March 1943. It comes a few months after the ‘Beveridge Report’ had been published, with its call for post-war Britain to embrace a comprehensive welfare programme to tackle deep-seated social ills – a progressive ideal which was anathema to Churchill and which he had therefore spent time rubbishing in Parliament.

Adelaide Poole, like many Britons, was unconvinced by Churchill’s approach to domestic politics but held him in high regard as a resolute war leader. At certain moments, however, and especially when people were frustrated by a lack of good news from the battlefront, it was hard to separate the two roles.

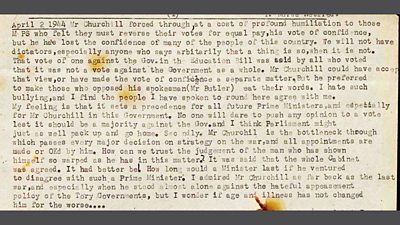

Here, for instance, is Adelaide Poole on 2 April 1944, losing all patience with the Prime Minister, after another of his performances in Parliament had been reported on the ����ý:

As for relations with the ����ý, Churchill’s attitude had been shaped well before the war. During the 1926 General Strike, he had wanted to take it over and turn it into a government mouthpiece.

Later, he also felt – with some justification – that the ����ý was sometimes excluding him from the airwaves because he was judged a maverick rather than someone representing official Conservative opinion.

The development of this thorny relationship has been traced by Malcolm Frost in his interview for ����ý Archives. Frost would go on to be an important figure in the wartime ����ý – setting-up the Monitoring Service, joining MI5, working with Eisenhower at the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

In many of these capacities he had dealings with Churchill. But his first encounter came back in 1929, when Frost was still involved in running a private ‘transcription’ service, which rebroadcast programmes from abroad:

Churchill’s enduring distrust of the ����ý could occasionally manifest itself in strange and unpredictable ways.

In this oral history interview, Norman Collins, who later ran the ����ý’s Forces Programme, recalls an encounter during his time as an in-house ����ý censor:

One final – and even more bizarre – Churchill episode is recalled by John Green, who worked in the ����ý Talks Department. Green was himself a proud Conservative, an admirer of the man. But he was also struck by his unpredictable behaviour.

On this occasion, it involved a chance encounter between Churchill, who was not yet Prime Minister, and a fellow ����ý producer, Guy Burgess, who was later revealed to be a Soviet spy:

Further reading:

- Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom, Volume III: The War of Words 1939-1945 (1995)

- Julian Jackson, A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle (2018).

- Richard Toye, The Roar of the Lion: The Untold Story of Churchill’s World War II Speeches (2013).

Related links

-

Voice of Cambridge spy Guy Burgess revealed Guy Burgess giving his own account of the meeting with Churchill