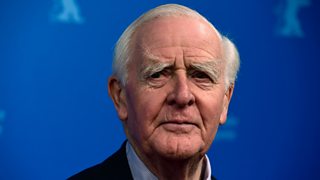

In his own words: The memoirs of John le Carré

14 December 2020

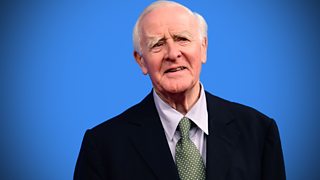

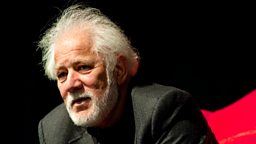

John le Carré, who has died at the age of 89, was one of Britain's greatest writers. In 2016, as his memoir The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life was published, BRIAN MORTON examined le Carré's life, work and philosophy alongside highlights from ����ý interviews.

From his years serving in British Intelligence during the Cold War, to a career as a writer that took him from war-torn Cambodia to Beirut, and Russia before and after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the fiction of David Cornwell - better known as John le Carré - has always got to the heart of modern times.

Towards the end of le Carré’s fourth novel, The Looking Glass War, the loyal, doomed returning agent Fred Leiser - who shares something of George Smiley’s troubling vulgarity of aspect - tells a German girl about something that happened to him back in London.

He was walking by the river and stopped to watch a pavement artist working in the rain, still drawing even though his picture was washing away as it was created.

It’s the perfect image for how le Carré functions as an artist and how even the clearest details of narrative blur and slip the moment we have them securely in mind, how character and personality are shifting, uncertain qualities.

Leiser remembers the picture as showing “dogs, cottages, and that”, which is perhaps intended to reflect the world we leave behind for ever when we enter the secret world.

Dogs don’t generally fare well in spy fiction (too obviously faithful, perhaps) and cottages are more often places of homosexual entrapment than peaceful retirement. The use of “and that” is just another little sign that Fred isn’t quite one of us, the self-elected Set that stands behind England’s crumbling imperial mission.

Le Carré has long protested that he is no expert on the spy trade, even though he was part of that world for some time. He does so again in his first book of non-fiction, The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life.

Sympathetic critics have endorsed his demurrals, arguing that le Carré happens to use the mechanisms of spy fiction to write about wider human issues: the betrayal of friends, the psychic outcomes of a concealing childhood, men and women and why the former really don’t understand the latter.

When Eric Homberger wrote a pioneering monograph about le Carré in 1986, he was unaware of the actual extent of the author’s involvement in secret intelligence.

The Pigeon Tunnel, rich in name-dropping encounters – Yasser Arafat, Rupert Murdoch, Margaret Thatcher... and some nicer people – is a pleasing, teasing exercise in that old game of Find The Original.

We know that James Bond is compounded of a daring brother, Biffy Dunderdale, Conrad O’Brien-ffrench, and the borrowed name of a Caribbean ornithologist.

The Pigeon Tunnel is rich in name-dropping encounters – Yasser Arafat, Rupert Murdoch, Margaret Thatcher... and some nicer people.

We aren’t quite as clear about who went into the making of George Smiley, with his bookie’s clothes and interest in German literature, and le Carré is happy to drop hints. Just as he is to share the understanding that Rick Pym, in the transparently autobiographical A Perfect Spy, is drawn from Rick Cornwell in the same way that Magnus Pym is drawn from his son, née David Cornwell.

On the matter of names, he tells a grand story of nervously answering a phone in a Beirut hotel while the usual Beirut firework display went on outside, responding to the name “John”, because that’s how people who don’t know him think of him, and finding himself at the sharp end of a tongue-lashing, transcribed in The Pigeon Tunnel with full obscene relish, from a wife or girlfriend who believes that her John is up there shagging some floozy.

Le Carré (and he tells this bit very much in novelist mode) suggest that they have a drink in the bar to patch over the misunderstanding, but when he gets down, there’s no woman there, just a couple of murky arms dealers.

More recent critics, armed with more understanding of Cornwell’s actual involvement in spying – which was low-level, albeit at an interesting time – have resorted to arguing a congruence between spying and writing fiction, as if le Carré’s early subject, and indeed that of many of his post-Cold War books is simply a trope for what the novelist does: observing, spinning yarns, stealing secrets, reversing coats and identities.

Even sympathetic observers suggest that le Carré was merely marking time, waiting for the Wall to come down so that he could get on with his real subject, which doesn’t require Cold War geopolitics, just people.

Homberger, though, got it dead right when he identified le Carré’s vision and method as Forsterian, or maybe post-Forsterian. The novels, taken in whole, are a perfect dramatisation of Dean Acheson’s famous comment about England having lost an empire, but not yet found a role.

The strain runs deepest around EM Forster’s most famous utterance. While everyone remembers that Forster hoped he would have the guts to betray his country rather than a friend, hardly anyone remembers that he began the point by saying “I hate causes”.

The Cold War is still Le Carré’s big subject because the Cold War has never ended; it is merely carried forward by different means and different men

He was much too refined a writer to put the offending word in scare quotes, but in le Carré’s work ideologies of every kind come with precisely that sarcastic and dismissive emphasis. He hates causes, too, to precisely the level that they overspill and overrun the human.

There is about The Pigeon Tunnel a faint echo of Mrs Thatcher’s famous mot, also usually redacted, about there being no such thing as society, just men and women.

Le Carré is wise enough to know that while the latter state is the ideal one, the former prevails. We can’t get away from huge, reified structures and causes, each functioning according to its own rules, each a juggernaut that crushes individuals without a murmur.

The Cold War is still le Carré’s big subject because the Cold War has never ended; it is merely carried forward by different means and different men. Gangsterism has been rebranded as market capitalism; socialism has been rebranded as gangsterism.

Le Carré says that The Pigeon Tunnel, with its reference to a shooting gallery near the Monte Carlo casino, stocked with birds for the convenience of sporting gentlemen, has been the working title of pretty much all his books at one time or other.

The stories gathered here, some of which will be familiar in other forms and voices, aren’t simply footnotes (to be filed under “non-fiction”) on those earlier books. Nor are they an essay in episodic autobiography. They are, perhaps, the greatest novel le Carré has written, just as the earlier novels were privileged and sometimes dangerous glimpses into the unreality of the “real” modern world.

- A version of this article was originally published in September 2016.

- Read the ����ý News obituary for novelist John le Carré, born 19 October 1931, died 12 December 2020.

Le Carré in his own words

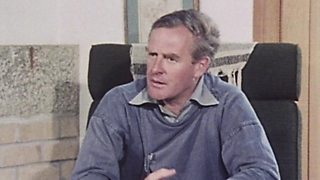

On being "severely discouraged" from becoming a writer: In a 1966 interview, le Carré tells Malcolm Muggeridge about his early forays into stories, poetry and art. .

On the difference between the thriller and the novel: The author talks to Michael Dean about the "feeble" debate, and spells out his definition of the novel, during an interview originally broadcast in 1974.

On why James Bond shouldn't be classed as a spy: Speaking to Malcolm Muggeridge in 1966, the author says Ian Fleming's creation is merely an "international gangster" who's "entirely out of the political context".

On inventing his own language: Speaking to Melvyn Bragg in 1976, the writer discusses some of the words and phrases he coined in his novels, such as 'honey-trap', 'lamp-lighters' and 'mole'.

On running away from school: Le Carré describes the moment he had to choose "between God and the Devil" during an interview with Melvyn Bragg originally broadcast in 1979.

Le Carré on ����ý Books

-

![]()

From his past as a spy to the autobiographical aspects of The Night Manager, ����ý Arts reveals what makes the great author tick.

Le Carré on ����ý iPlayer

-

![]()

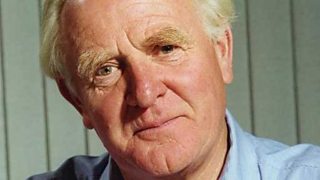

First transmitted in 1966, Malcolm Muggeridge talks to John le Carré, who at the age of 34 had written the best-seller The Spy Who Came In From The Cold.

Le Carré on ����ý Radio

-

![]()

James Naughtie and a group of readers from the Morrab Library in Penzance, Cornwall, talk to John le Carré about his Cold War spy trilogy.

-

![]()

In a special interview, Mark Lawson talks to John le Carré, whose latest novel, A Most Wanted Man, examines Hamburg's role in the War on Terror.

-

![]()

Mariella Frostrup talks to Adam Sisman about his biography of thriller writer John le Carré, creator of the bestselling Smiley novels and many more.

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

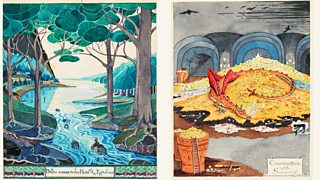

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

More from ����ý Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms