Beyond A Clockwork Orange: Anthony Burgess at 100

28 June 2017

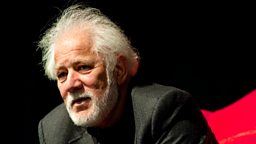

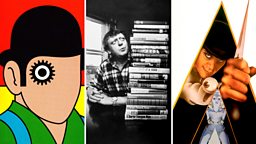

As the Manchester International Festival celebrates native son Anthony Burgess with two centenary events, BRIAN MORTON re-discovers the literary and musical legacy of an author and composer still best known for the film adaptation of his novel A Clockwork Orange.

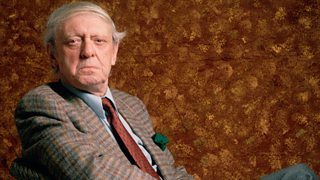

He’s remembered now chiefly for a novel more often talked about than read and for the film based on it which disappeared from public view for decades after its director’s decision to withdraw and effectively disown it. Think Anthony Burgess and most people think , about which they will have strong views, usually unsupported by actual viewing or reading.

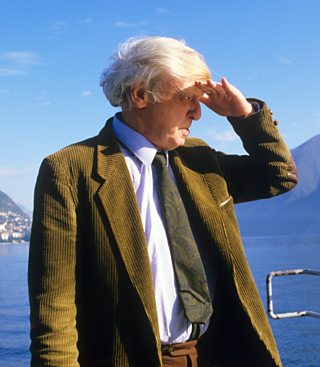

Burgess’s centenary finds his reputation in a rather tattered state, with the greater part of his work neglected and unrevived. He predicted that he would die “in the Mediterranean lands, with an inaccurate obituary in the Nice-Matin, unmourned, soon forgotten”. He was right in all but the place of death, for he actually succumbed to lung cancer in grimy London, though he arranged to be buried in Monaco, where he had made his home for some years.

Burgess鈥檚 centenary finds his reputation in a rather tattered state, with the greater part of his work neglected and unrevived

Now, though, the is looking to redress the balance with two events dedicated to the Manchester-born author and composer. is an audio-visual art installation based on a Burgess novel, while is a concert celebrating Burgess the writer of music.

For all his once-high public profile in the United Kingdom as a journalist and broadcaster, and more academic reputation in the United States, he is now surprisingly undervalued as a writer and virtually unknown as a composer.

Only the American novelist and short story writer managed to sustain parallel literary and musical careers, but where Bowles largely abandoned composition, Burgess returned to his first love late in life and regularly expressed the hope that his musical reputation would grow in his native country.

Perhaps inevitably, music played a significant role in his writing, not just as a theme but as a structural device. His 1974 novel deploys that overworked fictional analogy with more than usual success, a work divided into four distinct “movements”, each with their defining signatures and keys.

A very dominant musical strain runs through , but it’s often forgotten that the macaronic Nadsat language of the text – a blend of English and Russian argot – has something of the improvisatory quality of Burgess’s beloved jazz.

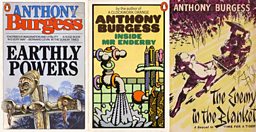

Arguably his major fictional achievement, the sprawling Earthly Powers is also organised symphonically, or perhaps operatically, with frequent use of leitmotif (like the almost obsessive rendering of “venerean strabismus”), transitions of mood and large-scale resolutions.

For all his shambolic public persona, which was as much a self-creation as “Anthony Burgess” which were the middle names of the plainer Lancashire Catholic born as John Wilson, he was a man of enormous general culture, pleasurably addicted to long words (a venerean strabismus is a sexy squint to you and me), but more effortfully cosmopolitan (since Abroad often made him sick, or think he was).

His speaking voice was rich and fruity and sometimes more than a little pleased with itself, but then there was a lot to be pleased with.

He was a man of enormous general culture, pleasurably addicted to long words

There were more than thirty novels from the early , based on his experience at a teachers training college in Khata Baru, to the posthumously published Byrne, a novel in verse with its own musicality.

He wrote, as Joseph Kell, a sequence of novels about the poet Enderby, a comic-fantastic version of himself, perhaps.

No less a critic than thought that was the most undervalued English novel of the age. It’s more than worth rereading. It still turns up occasionally in junk-piles, the Kell pseudonym unrecognised.

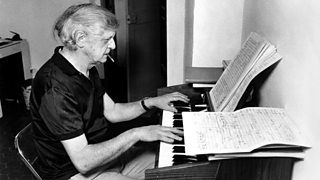

If the writing is at a critical discount these days, the music is almost entirely unheard and deserves revival.

Academic composers and rigorous critics would quickly find symptoms of autodidacticism in Burgess’s processes: too many harmonies based on fourths, or sudden shifts into atonal territory; too strong a reliance on rhythm to drive through a shaky conception. He wrote a symphony at 20, as 20 year olds do, and then defaulted to a Sinfonietta for jazz group, which was more in keeping with his skills at the time.

While teaching in England, he played with and wrote for a dance band, even attempting a musical version of , a tragedy co-written by W. H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood. He made interesting settings of his own Mr Enderby and a Joycean opera , which was broadcast in 1982, but now seems lost.

Late in life, living largely in Monaco to avoid tax, he was enchanted by the classical guitar and wrote a number of works for guitar quartet, alone and with orchestra. The latter piece was called Concerto Gross, a typically pawky Burgess variation on the usual concerto grosso.

The title might well be borrowable for a biography. Burgess was no Tom Wolfe dandy. He liked to appear dishevelled, with greasy hair all over the place, fleshy-faced and perpetually wreathed by the cigarette smoke that eventually killed him.

He looked and sometimes acted like an expat planter, but the mind inside and the virtuoso use of language were in the sharpest contrast to the exterior. His own earthly powers were titanic, and their moment may yet come round again.

From the 大象传媒 archives

Burgess at 100

More Anthony Burgess

by Graham Eatough and Stephen Sutcliffe runs at The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, from Friday 30 June to Sunday 16 July 2017.

by Raymond Yiu and performed by the 大象传媒 Philharmonic is on at Manchester's Bridgewater Hall on 4 July 2017.

This article has been updated and was originally published on 23 February 2017.

MIF17

-

![]()

The hottest shows - many of which can be watched online.

-

![]()

Test your knowledge of the city's cultural icons.

More from 大象传媒 Arts

-

![]()

Picasso鈥檚 ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms