The Baillie Gifford Prize 2016: Real life writ large

16 November 2016

The four books shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize took in an abducted father, the hidden lives of America's black elites, the origins of international law and the collapse of the Soviet Union. As BRIAN MORTON finds, the line between fiction and non-fiction remains deceptively fluid.

In a famous essay published in the Tribune newspaper in 1946 called “”, George Orwell pictures a downtrodden freelance hack in a chilly bedsit, wearily tearing the wrappers off his latest assignment; 800 words, due by midday tomorrow, on “Palestine at the Cross Roads, Scientific Dairy Farming, A Short History of European Democracy (this one 680 pages and weighs four pounds), Tribal Customs in Portuguese East Africa, and a novel, It’s Nicer Lying Down, probably included by mistake.”

Portmanteau reviewing has gone somewhat out of fashion. These days, the kind of people most likely to take delivery of such a wildly eclectic bunch and absurd deadline are book prize judges, who generally find they need a nice lie down as soon as the process is over.

The dividing line between fiction and non-fiction isn鈥檛 quite as hard and fast as it used to be

Orwell’s wry mention of a novel was, of course, supposed to flag up how unseriously polite fiction was taken by the Fleet Street of his day.

In the case of a non-fiction book prize, like the Baillie Gifford (formerly the Samuel Johnson Prize) the inclusion of It’s Nicer Lying Down would most certainly be a mistake. Or maybe not.

The dividing line between fiction and non-fiction isn’t quite as hard and fast as it used to be or as librarians (a species heading for extinction even faster than book reviewers) might like.

Private Eye recently excoriated the Baillie Gifford shortlist for 2016 on the grounds that all four books were examples of personal testimony or “journey” rather than objective reportage and analysis. In a very minor way, “Bookworm” had a point.

Structurally, Hisham Matar’s (Penguin Viking) is indistinguishable from a work of fiction. It is, after all, the work of a fine novelist whose debut book In the Country of Men deals with similar backgrounds and themes.

Likewise Margo Jefferson’s (Granta), whose narrative voice is genuinely novelistic. Sometimes it’s only the presence of a subtitle or a sonorous “on the . . . (insert big theme here)” which gives away non-fiction status.

Philippe Sands’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) sounds like a book that might have begun life as a thesis rather than a personal journal, but it, too, draws on the experience of two individuals, Nuremberg prosecutors who discover that the Holocaust has touched them far more closely than they had realised.

The blurring of fiction and non-fiction is supposed to have happened with the rise of New Journalism, whose first-person urgency, demotic voices and participatory logic led to Truman Capote’s Norman Mailer’s non-fiction novels (starring Norman Mailer), ’s visionary essays and, drawing from 1930s experiments like and the , Studs Terkel’s vividly tape-recorded testimonies from ordinary Americans.

Real-life books are hot product right now because what otherwise passes for real life has acquired an uncomfortable postmodern shimmer

The final work in this year’s Baillie Gifford shortlist is such a work. Svetlana Alexievich’s (Fitzcarraldo Editions) brings to life the collapse of the USSR not through geopolitical analysis but in the voices of those who experienced it first hand: an ensemble work, orchestrated like one of ’s encyclopaedic sagas of American life.

Fact is, non-fiction became popular again when readers began to tire of the repetitive pretensions of postmodern fiction.

Biography began to and still sells briskly because it tends to follow a reassuring trajectory of beginning, middle and end. Autobiography adds the grain and timbre of a recognisable voice. A white-hot personal account of childhood abuse, imprisonment, illness – or here, life in Libya, among Chicago’s black elite, in post-war Europe and at the end of the Soviet empire – is more readable than a footnoted monograph, bristling with bibliographical citations.

I only once sat on a non-fiction book prize jury and would have given both eye teeth for a readable memoir or personal story to replace one or more of the doorstopping monsters the postman (to whom I had to pay compensation for a damaged back) lugged to my door.

The most egregious of them spun the thirty-odd pages worth of known facts about Cardinal Wolsey (which is 29 pages more than we really know about Shakespeare) into a 600-page epic of supposition and conjecture.

Book prizes are about books and books are for readers, not for library stacks or for a reciprocal appearance in someone else’s bibliography. Real-life books are hot product right now because what otherwise passes for real life has acquired an uncomfortable postmodern shimmer.

We crave the authority of a voice that says “I was there”, “this happened to me”, “it was like this”.

Philip Roth never bought into the mannerisms of New Journalism but he understood the phenomenon, arguing that fiction and non-fiction were no longer meaningful categories. Life, he said, divides rather into the unwritten and the written.

On Tuesday 15 November 2016 the for Non-Fiction was awarded to Philippe Sands for his book East West Street (Weidenfeld & Nicolson).

This article was originally published on 15 November and updated on 16 November 2016 to name the winner of the prize.

Explaining the four book shortlist

Thomas Keneally on the girl in red in Schindler's List

The author discusses the scene in his book, made famous through Steven Spielberg's film.

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between, Hisham Matar, (Penguin Viking): Matar was nineteen when his father was kidnapped and taken to prison in Libya. 20 years later, he returns to Libya to find his father and rediscover his country.

Negroland: A Memoir, Margo Jefferson (Granta): The daughter of a successful paediatrician and a fashionable socialite, Margo Jefferson details the the little-known world of America's black upper-classes.

East West Street, Philippe Sands, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson): Digging into his own family's history, author/lawyer Sands embarks on an exploration of the origins of international law through Nazi-occupied Poland.

Second Hand Time: The Last of the Soviets, Svetlana Alexievich, (Fitzcarraldo Editions): the winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature collates a fascinating oral history of the collapse of the Soviet Union from the testimonies of people who lived through it.

More from Books

-

![]()

Seven must-read novels by female authors.

-

![]()

Tolkien's own illustrations of his fantasy universe.

-

![]()

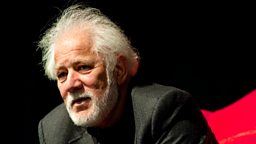

The author picks his three favourite works of science fiction.

-

![]()

Judge these books, and their genres, by their covers.

More from 大象传媒 Arts

-

![]()

Picasso鈥檚 ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms