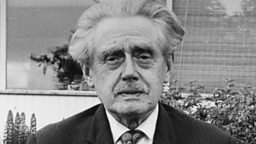

William McIlvanney

1936 -2015

Biography

William Angus McIlvanney was born on 25 November 1936 in Kilmarnock, the youngest of four children of an ex-miner who had taken part in the General Strike of 1926. (His brother Hugh became a distinguished sports journalist.) His father died when McIlvanney was eighteen, an experience reflected in his first novel Remedy is None. He was educated at Kilmarnock Academy and studied English at the University of Glasgow, graduating MA in 1960. The first member of his family to go to university, he ‘became progressively unimpressed... With some very honourable exceptions, I couldn’t accept the mechanistic shallowness of much that was on offer’. He entered teaching, reaching the position of assistant headmaster, but resigned to become a freelance writer in 1975.

McIlvanney’s appreciation of his working-class heritage is a mainspring of his writing. At university he found that none of the texts in his literature course dealt with the working-class life which he knew from his own experience to be rich in character, intelligence and incident. In his own work he has aimed to correct this imbalance, and has been rewarded by reactions like that of an old miner to his novel Docherty: ‘You told my story’. Like other Scottish writers, he was greatly disappointed by the failure of the 1979 devolution referendum and disturbed by the erosion of social idealism in the Thatcherite eighties; and this political unease has given rise to some of his strongest writing: see for instance the essays collected in Surviving the Shipwreck (1991).

As well as publishing novels, short stories and poetry, McIlvanney has had a parallel career in journalism and as a TV presenter. He has held writing fellowships in Scotland and Canada. Among other awards, he received the Whitbread Prize for Fiction for Docherty in 1975, and the Glasgow Herald People’s Prize for his short story collection Walking Wounded in 1990. His novel The Big Man was filmed with Liam Neeson in the title role, and he collaborated in the filming of his short story ‘Dreaming’, shown at film festivals and on television in 1990.

(Last updated in September 2004)

Works

It has become clear over the course of McIlvanney’s career (he's not a markedly prolific novelist, he produced eight novels and a short story collection in thirty years) that since at least his third novel, Docherty, he has in fact been writing what has been called ‘one single great mosaic-like West of Scotland fiction’. His novels and stories are generally set in or near the town of Graithnock (a thinly disguised Kilmarnock) or Glasgow, but the link becomes more obvious with the appearance of recurring characters. Though some critics divide McIlvanney’s work into ‘serious’ and ‘detective’ novels, he himself resists such a distinction, and it is no longer possible even to say that they constitute two different series.

The Kiln (1996) brings some pieces of the picture together. Tom Docherty, the central character, is the son of Conn and grandson of Tam from the earlier novel Docherty, and a schoolmate of Jack Laidlaw, the detective hero of three other novels. Now a middle-aged novelist living alone in a rented flat in Edinburgh, he looks back over his life. Memories of his family and his failed marriage emerge in apparently random order (in fact they are precisely placed), but he returns continually to the summer when he was seventeen, between school and university, working in the local brickwork – the kiln. This is the central image of the novel. McIlvanney indicates that in this milieu of hard work, rough company, and the menace of the factory bully; the boy will either harden into a man or crumble like an ill-made brick. It is also the summer of Tom’s first attempts at writing and, most important in his estimation, of his quest for sexual experience. Past and present intertwine in an impressive and mature novel which seems to contain much of McIlvanney’s own experiences, doubts and beliefs.

Laidlaw (1977) surprised many critics who had admired McIlvanney’s first three novels. Since his fourth has a Glasgow detective inspector as central character and deals with a violent rape and murder, they categorised it as a crime novel and considered that the author had gone downmarket. This was a misreading of McIlvanney’s intention and of the novel itself. He has said that Laidlaw is ‘not a whodunnit [but] a whydunnit’ (we know the identity of the murderer from page one) and ‘less an example of the traditional detective story than an attempted challenge to it’. Jack Laidlaw, like other fictional detectives, is a maverick, a university dropout, a rebel against authority and an unfaithful husband. Particularly notable, however, is his empathy with the criminals he pursues, not because he approves of their crimes but because he knows that he himself is flawed. Laidlaw is a complex character and acknowledges the complexity of life: everyone is a mixture of good and bad, and the frontier between law-abiding and criminal is narrow and easily crossed. The background to the Laidlaw novels is the city of Glasgow, a symbol of this complexity, famously combining humour and kindness with deprivation, ugliness and cruelty.

Docherty (1975) begins with the birth of Conn, the youngest child of miner Tam Docherty, at the end of 1903 in the West of Scotland mining town of Graithnock. Though much of the action is seen through Conn’s eyes, the novel’s central character is Tam: ‘He’s a wee man but he makes a big shadda’. He is presented as a figure of staunch decency and unassuming courage, who is, in addition, constantly questioning received ideas of religion, politics and society. Through him and his sons, McIlvanney unrolls the history of the Scottish working class in the early twentieth century. Tam announces that things will be different for the new baby: ‘Ah’m pittin his name doon fur Prime Minister’, but even higher education is an impossible dream. Indeed Conn chooses to follow his father down the pit. This is in accordance with McIlvanney’s purpose of depicting the richness of working-class life: to leave the home environment would be to indicate that it is inferior. (By the time of The Kiln, Conn’s son Tom has made the transition to the middle class.)

Strange Loyalties (1991) is another novel which links different strands of McIlvanney’s work, being to some extent a continuation of The Big Man (1985) but more importantly the third Laidlaw novel. It is narrated for the first time by Jack Laidlaw himself, allowing the reader further insight into his thoughts and emotions. His brother, Scott, has died, having staggered drunk into the path of a car. Jack is not satisfied with the explanation that it was an accident: ‘Where did the accident begin? … When did the accident begin? And why?’ He takes a week’s leave and goes in search of the truth. It seems to be connected with an enigmatic painting of Scott’s, and with a night sixteen years ago when he destroyed all his work from art school. The final discovery, as often in McIlvanney’s work, raises as many questions as it answers.

(Last updated in September 2004)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall