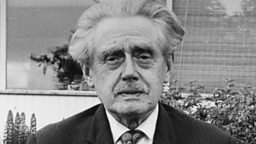

Robert Henryson

1450 - 1505

Biography

There is very little hard biographical fact regarding the life of the medieval poet, Robert Henryson, and what can be gleaned is simply patched and stitched together from scant evidence, historical, literary and otherwise. While critics differ on the poet’s birth date, suggesting years anywhere between 1425 and 1450, it seems reasonable to suggest that he is the Robertus Henrisone to be found in the 1462 records of the University of Glasgow. While this connection is speculative, the notion that Henryson was university-trained gains further credence when one considers the vast and sophisticated learning to be found throughout the poet’s corpus, and the fact that William Dunbar, among others, refers to him in his ‘Lament for the Makars’ (c.1506) as ‘Maister Robert Henrysoun’, indicating Henryson had a Masters degree.

Dunbar also associates Henryson with the kingdom of Fife, and in early editions of his work, he is referred to as Dunfermline’s schoolmaster. The school was a place of particular educational prestige and culture, being linked to the neighbouring Benedictine Abbey. The status and fortune of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland at this time was considerable, and Henryson’s post associates him with its prosperity and reputation. Connected with this is the speculation that Henryson worked as a legal representative for the abbey. We may never know the truth of Henryson’s life, but the portrait tentatively drawn by critics and historians is of a man of no small importance, in both civic and literary terms.

Similarly, there is no confirmed evidence of the date of the poet’s death. In ‘Lament for the Makars’, which contains the refrain ‘Timor Mortis Conturbat Me’, translated as ‘the fear of death perturbs me’, William Dunbar bemoans the deaths of major Scots poets. The poem, written around the end of 1505 or beginning of 1506, includes Henryson’s name amongst the roll call of deceased writers. Henryson’s work is timeless, and its gentle humanism suggests a sympathetic and erudite man.

Works

Robert Henryson is, alongside and , one of Scotland’s major medieval ‘makars’ or poetic ‘makers’. While the term ‘makar’ appears to denote a down-to-earth approach to poetry, which ‘crafts’ and ‘makes’ literature, and which suggests the use of hands rather than minds, this is only one side of the story. The poets’ practice demonstrates their sophisticated method: works must be rhetorically planned in advance, and learning and refinement must be continuously visible. The medieval period, in many ways as complex and sophisticated as our own, is the necessary context in which we must judge the work of Robert Henryson.

In Henryson’s period, the place of human individuals in the world was, in theory, more clearly defined than ours is today. Medieval literature repeatedly describes a world of hierarchy, definite restrictions and collective beliefs. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Henryson’s , an impressive, many-layered collection of thirteen fables, translated into Scots from the European tradition of Aesop.

Henryson’s ‘Prologue’ describes his method and aim for his Fables, and exemplifies a crucial strand of his overall poetic protocol: ‘to repreif the haill misleving/ Of man, be figure of ane uther thing’. In other words, Henryson seeks to reprimand man’s wickedness by analogy and moral instruction. He intends to delight as well as teach and promises ‘Amangis ernist to mix ane merie sport’ – to mix solemnity with joviality. Throughout the cycle of Fables, Henryson compares men to ‘beistis’, and urges them to abandon bestial ‘carnall and foull delyte’ to embrace their noble spiritual side.

In Henryson’s Morall Fabillis, the popular and comic ‘Taill of the Lyon and the Mous’ blends with less known, but equally powerful Reynardian fables, such as ‘The Cock and the Fox’ and ‘The Fox and the Wolf’, to create a masterful collection which deals in the universals of human life and which surpasses its originals in its ambition and detail. Many of the Fables translated by Henryson have become part of public consciousness. ‘The Taill of the Uponlandis Mous, and the Burges Mous’, or ‘The Two Mice’, for example, relates the legendary story of the town and country mouse, often anthologised in children’s literature to this day.

While Henryson remains faithful to his European originals, he adds his own distinctive touch to his tales. As well as translating the fable itself into luxurious vernacular Scots, Henryson provides a clear ‘Moralitas’, or moral, in which the central message is communicated. The moral of ‘The Two Mice’, for example, is a common one in medieval literature, and counsels that one should stay in one’s allotted place in life, and warns against the example of ‘thay quhilk clymmis up maist hie,/That ar not content with small possessioun.’ The tone of the Fables darkens as Henryson approaches the end of his collection, and the final tale, ‘The Paddock and the Mouse’, faces the dark reality of man’s transitory life on earth. Henryson asserts that death can come at any time, and so we must always be spiritually ready: ‘mak the ane strang castell/ Of gud deidis, for deith will the assay,/ Thow wait not quhen – evin, morrow, or midday.’ In other words, man must construct a solid castle of good deeds which will ensure salvation on his death.

Henryson wrote various sizeable poems, including the French-influenced mock-pastoral, Robene and Makyne, and the classically based Orpheus and Euridyce, a piece which queries the romance genre. However, it is in The Testament of Cresseid that we find him at the heights of his erudite, sumptuous, humanist literary power. Taking up the story of Chaucer’s heroine of Troilus and Criseyde, Henryson provides one of the most multifaceted and intricate portrayals of the human condition in Scottish literature.

Unsatisfied with Chaucer’s conclusion for Cresseid, Henryson decides in the first few stanzas, to fill a gap, concerning ‘the fatall destenie/ Of fair Cresseid, that endit wretchitlie’. Describing her ‘desolait’ exclusion after her betrayal of Troilus and abandonment by the lustful Diomede, Henryson relates her rash but desperate blasphemy against Venus and Cupid for her bad fortune in love: ‘O fals Cupide, is nane to wyte [blame] but thow/ And thy mother, of lufe the blind goddes!’ Cresseid’s blasphemy accelerates her ruin, and, as she dreams that night, she is tried by a court of planetary gods and afflicted by leprosy as a punishment. The regretful and repentant theme of her complaint is one of the most evocative and poignant passages of Scottish literature, and her message is sadly clear and universal: ‘Nocht is your fairnes bot ane faiding flour,/ Nocht is your famous laud and hie honour/ Bot wind inflat in uther mennis eiris … Fortoun is fikkill quhen scho beginnis and steiris!’

Henryson’s poetic voice is human and demonstrative, but also elegantly literary. All at once, he is preacher, adviser, teller of love stories, sympathiser with and punisher of human imperfection. His remarkable output stands as an indispensable classic of Scottish literature, and his presence is vital.

Primary��

The Morall Fabillis of Esope the Phrygian

The Testament of Cresseid (1568)

Orpheus and Eurydice��

Robene and Makyne

The Poems of Robert Henryson,��ed. by Denton Fox��(1981)

Robert Henryson, The Testament of Crisseid��ed. by D. Fox (1968)

Secondary/Anthology

��The Mercat Anthology of Early Scottish Literature, vol. 24, no. 2,��ed. by R. D. S. Jack and P. A. T. Rozendaal ��(2003)��

Kratzmann, Gregory, 'Henryson's Fables: 'the subtell dyte of poetry.''��Studies in Scottish Literature 20 (1985) pp. 49-70.

Machan, Tim William. 'Robert Henryson and Father Aesop: Authority in the Moral Fables.' Studies in the Age of Chaucer 12 (1990) pp. 193-214.

MacQueen, John, Robert Henryson: A Study of the Major Narrative Poems (1967)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall