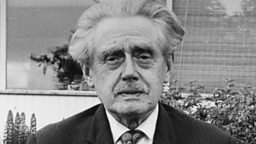

Robert Louis Stevenson

1850 - 1894

Biography

Born in 1850, Robert Louis Stevenson grew up in Edinburgh where his father was a well-respected lighthouse engineer. Stevenson almost followed his father’s example, studying engineering at Edinburgh University, but at twenty-one decided to become a writer.

His early works consist of essays and travel writing, his first book, An Inward Voyage (1878), describes a canoe trip to Belgium and France. Despite his success with this style of writing and having been a writer of fiction since his teens, it was not until 1877 that his first work, a short story, was published.

In 1882, Stevenson began to publish longer fiction and Treasure Island was serialised at this time. Kidnapped (1886) followed with critical success but it was The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) which was to bring Stevenson fame on both sides of the Atlantic. Kidnapped, a fast paced adventure tale, is also a subtle examination of Scottish history and character. These issues were to be integral to his writing. Jekyll and Hyde, while exploring the duality of good and evil, was also a criticism of Victorian morality.

Stevenson flouted convention, rejecting the hypocrisies of Calvinist Scotland, preferring a bohemian lifestyle in France where he met his future wife, Fanny Osbourne, an American divorcee, ten year his senior. He spent time in the American west with Fanny before voyaging even further west, into the Pacific.

His travelling also had the purpose of keeping the writer in warmer climates which were more suited to his health. He was eventually to settle with his family in Samoa in the South Seas, though he did not know, when he arrived, that he was to remain there for the rest of his life. His writing continued to show the importance of his native country and his work is often set in Scotland or uses Scottish themes. His short stories and later fiction such as The Master of Ballantrae (1888) show the writer’s continuing interest in the effects of Scotland’s history on its people. The novels often feature two characters who appear as two sides of one character, each striving to achieve dominance; ultimately they destroy one another, unable to co-exist. This split self can be seen to act as a metaphor for Stevenson’s conception of a divided Scotland.

It was in Samoa that Stevenson was to write Catriona (1893), an unfinished sequel to Kidnapped and Weir of Hermiston (1896, also unfinished) which he was writing when he died in 1894 at the height of his literary power.

Stevenson has been acknowledged as one of the most important writers of Scottish fiction. His writing highlighted the social, philosophical and cultural divisions of nineteenth-century Scotland and has been the inspiration for numerous later writers.

Works

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde considers the notion that humanity possesses an innate capacity both for good and evil, but that only by suppressing this dark side can we make pretence at civilised respectability. The two doors to Dr Jekyll’s house represent his split character. The covert, concealed entrance used by Hyde is a marked contrast to the public door used by the respected doctor. The concept that morality is merely a public facade is played to extremes. Hyde is a monster, small and quickly able to conceal himself, as his name suggests. The violence and ugliness characterised by Hyde represent the dark underbelly of society.

To be wholly devoted to some intellectual exercise is to have succeeded in lifeRobert Louis Stevenson

It is a short but complicated text; a masterpiece of timing and disclosure helped by the use of letters and multiple narratives. The text is meant to be unsettling and make us question whether we can ever be secure that our own dark side will not emerge. There is an insidious evil within Jekyll and it shocks us that a respected pillar of society is capable of murdering children. Jekyll’s is not a supernatural change; but man-made, scientifically constructed. Jekyll and Hyde appear to be polar opposites but they cannot survive together. Yet they also need each other dependently. The story must end in death because both sides cannot be sustained and will burn one another out. There is a sense of moral retribution for Jekyll, who would have been safe if only he had repressed his dark side. Nevertheless, there is no moral absolute. We recognise a frightening truth in Jekyll’s desire to allow Hyde his own self-expression. The story’s continued relevance relates to its ability to make the reader engage with moral questions which apply to any period of history.

Stevenson’s works and especially The Master of Ballantrae make no pretence that they will offer truth without ambiguity. This novel challenges the reader to take evidence from the multiple narrative accounts and try to piece together the contradictory versions of events. Similar to Jekyll and Hyde, James and Henry too cannot co-exist. However, there is the suggestion of a more radical idea: that good and evil are not necessarily in opposition and may exist simultaneously within one person. The notion of Henry representing good and James evil does not sit entirely comfortably. We are given no evidence to prove that either brother should be described in this way. The ‘evil’ characteristics of James, as detailed by one of the narrators, MacKellar, can be narrowed down to such activities as drinking, playing cards and seducing the local women. To MacKellar’s Calvinist way of thinking, such exploits are those of the devil. Yet, filtered through our own moral perspectives, James’s actions can be seen as youthful extravagances. They do not signal absolute evil, as MacKellar seems to believe.

Meanwhile, in the course of the story, Henry’s more ugly characteristics emerge, particularly in his explicit favouritism of Alexander over his daughter, for whom he has a profound disinterest. Stevenson endeavours to prevent the reader sitting at ease with straightforward, neat conclusions. The structure and the range of narrative voices encourage constant questioning and analysis. Similarly, the dual interpretations available and the development of Henry’s and James’s characters offer constantly shifting perspectives. These aspects invite further questions about the nature of morality and truth. Stevenson provides profound insight into a world in which moral codes are relative rather than absolute.

The theme of the unreliable narrator and ‘the double’ appear early in Stevenson’s work. In Treasure Island, the child moves in an adult world and must learn about adulthood and morality. Knowledge is the key to this development and the opening of Kidnapped also resonates with this. Kidnapped itself furthers the idea that factual understanding is important, as it is the language of adulthood. The last phrase of the novel’s first sentence signals the main character’s final move from childhood to the adult world: ‘I took the key for the last time out of my father’s house’. This contrasts with the first phrase of Treasure Island telling us that there is ‘treasure there not yet lifted.’ The treasure is used as a metaphor throughout the novel for the imagination.

There is darkness in these works but Stevenson thought that children should be taught and helped to face reality by showing them the good alongside the bad. Nevertheless, these works have suffered by being relegated to the sphere of children’s literature. Kidnapped is an adventure tale as well as a serious examination of Scottish history and culture. In fact, the child and the adult readings enrich one another.

Weir of Hermiston shares many features found in Stevenson’s earlier works. The key theme is the conflict between father and son. But it is the depiction of Christina which makes the book unique. Previous works are notable for their lack of female characters. The possibility that Christina might fall in love in this novel, opens new prospects for development. There is the suggestion of a pagan fatalism – rather than Christian preordination. The novel breaks the mould in this respect. Despite being unfinished, Stevenson’s notes indicate a violent, perhaps tragic ending to a novel itself notable for its brutality. Stevenson himself thought it was going to be his masterpiece.

Reading Lists

Primary

Treasure Island (1883)

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886)

Kidnapped (1886)

Underwoods (1887)

The Wrecker (1892)

Catriona (1893)

The Ebb Tide (1894)

Weir of Hermiston (1896)

The Master of Ballantrae (1897)

St. Ives (1897) (with Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch)

A Lowden Sabbath Morn (1898)

The Sea Fogs (1907)

The Meaning Of Friendship (1909)

Will O' The Mill (1915)

The Black Arrow: A Tale of Two Roses (1926)

The Beach of Falesa (1963)

Memoir of Fleeming Jenkin (2000)

Collections

New Arabian Nights (1882)

The Merry Men: And Other Tales and Fables (1887)

Ballads (1890)

Island Nights' Entertainments (1893)

Songs of Travel: And Other Verses (1896)

Virginibus Puerisque: And Other Papers (1901)

The Story of a Lie: And Other Tales (1904)

Tales and Fantasies (1905)

New Poems And Variant Readings (1918)

A Child's Garden of Verses (1921)

Moral Emblems and Other Poems (1921)

Selected Writings (1947)

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde And Other Stories (1964)

The Suicide Club: And Other Stories (1970)

The Supernatural Short Stories of Robert Louis Stevenson (1976)

The Body Snatcher: And Other Stories (1980)

The Robert Louis Stevenson Treasury (1986) (with Alanna Knight)

The Lantern-Bearers: And other Essays (1988)

Primary Non Fiction

Travels With A Donkey in the Cevennes (1879)

The Old and New Pacific Capitals (1880)

The Silverado Squatters (1884)

Memories and Portraits (1887)

Across the Plains: With Other Memories And Essays (1892)

A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892)

Vailima Letters (1896)

In the South Seas Being an Account of Experiences And Observations in the Marquesas, Paumotur And Gilbert Islands in the Course of Two Cruises, On the Yacht 'casco' (1888) And the Schooner 'equator' (1889) (1900)

The Amateur Emigrant (1988)

Short Stories

Thrawn Janet (1881)

The Body-Snatcher (1884)

Olalla (1885)

Markheim (1886)

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886)

The Bottle Imp (1891)

The Beach of Falesa (1892)

The Ebb Tide (1893)

The Isle of Voices (1893)

The Adventures of the Hansom Cab

A Lodging for the Night

The Master of Ballantrae (excerpt)

The Sire de Maletroit's Door

Something in It

The Song of the Morrow

Story of the Physician and the Saratoga Trunk

Story of the Young Man with the Cream Tarts

Secondary

Robert Louis Stevenson: A Life Study Jenni Calder (1980)

Robert Louis Stevnson and His World David Daiches (1973)

Andrew Noble, Robert Louis Stevenson (1983)

Robert Kielty, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Fiction of Adventure (1965)

Stevenson and Victorian Scotland, ed. by Jenni Calder (1981)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall