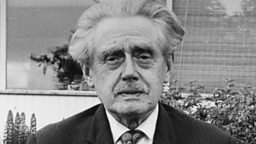

Allan Ramsay

1686 - 1758

Biography

Allan Ramsay was born in the village of Leadhills in Lanarkshire, on 15th October 1684. The poet was educated at Crawfordmoor Parish School, but when his mother died in 1700, he moved to Edinburgh to study wig making, eventually opening a shop in the capital’s Grassmarket. He married Christian Ross in 1712, and their eldest son, Allan, became an eminent portrait painter.

In the early 1700s, Ramsay began writing poetry, and founded, with like-minded associates, Edinburgh’s Easy Club. Formed in the wake of the 1707 Union with England, the club had nationalist and Jacobite sympathies, and although Ramsay had no involvement in the 1715 and 1745 Risings, his support for the Stuart cause is evident throughout his work. Club members took pseudonyms from literary figures, and Ramsay is first included in records as Isaac Bickerstaff, after a character in Richard Steele’s Tatler. On the club’s decision to change to Scottish names, Ramsay next called himself , after the medieval author of the Aneados (1513), a Scots translation of Virgil’s Aeneid. These pseudonyms demonstrate Ramsay’s attraction to English Augustanism and Scots classicism, and illustrate two icons of his work.

Ramsay’s first volume was a blend of English language and Scots poems, printed by the Scoto-Latinist Walter Ruddiman, in 1721. By this time, Ramsay was an established man of letters, his work providing the foundation on which and were to build.

Around 1720, Ramsay abandoned the wig-making trade, setting up business as a bookseller. His shop, near Edinburgh’s Luckenbooths, became the first circulating library in Britain. The poet was by now fully engaged in writing verse and collecting and editing older Scots literature, and in 1724 he published the first volume of Tea-Table Miscellany, a highly regarded and enduringly influential collection of Scottish song. In the same year, his The Ever Green amassed work of the medieval makars and of the seventeenth century.

Ramsay was famous during his lifetime as author of the Scots pastoral play, The Gentle Shepherd, which was published in 1725 and performed as a ballad-opera in 1729. On account of his interest in drama, Ramsay daringly opened a theatre in Edinburgh's Carruber’s Close. Calvinist objection to the theatre was fervent, and it was closed in 1737. Ramsay’s antagonism to Presbyterian dourness was thus further incensed, and he wrote numerous poems against what he perceived to be its hypocrisy.

Ramsay retired to a self-built house on Edinburgh’s Castlehill around 1740. His death on 7th January 1743 ended an innovative, genial and influential career. He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard.

Works

Allan Ramsay’s work is an essential ingredient to Scottish literature. His pioneering contributions to poetry and his collection and dissemination of ancient Scottish verse and song is invaluable, not only for the subsequent achievement of Robert Fergusson and Robert Burns, but also for and the ballad collectors. Without Ramsay, many Scottish works would be lost, and in his own writing and his role as compiler, he plays a large part in the construction of the Scottish literary tradition.

Ramsay’s Easy Club provided a stimulating atmosphere which nurtured his poetic talents, and it was here that he was first encouraged to write in the Scots vernacular. Ramsay is remembered as a Scots poet, but, like Fergusson, English language works play a role in his corpus. Whilst he was a champion of all things Scots and an opponent of the Union of 1707 which incorporated Scotland into Great Britain, he was aware of his British audience. Many critics have portrayed this as evidence of Ramsay’s duality, but English and Scots, then as now, need not be mutually exclusive.

Amongst Ramsay’s earliest works are his renowned comic elegies. In these verses, he renovates existing models by bringing a sense of grotesque but humorous realism to the sombre genre. The ‘Elegy on Maggy Johnston’ (all quotations are taken from the 1721 edition of Ramsay’s poems) mourns the death of a local brewer and tavern keeper. Ramsay delightedly describes scenes of chaotic drunkenness, and refuses to shy from the fact that her ale will be missed infinitely more than Maggy herself. Ramsay gives a jovial description of the ‘blyth’ sociability of drinking, but also its objectionable effects: ‘Ae simmer night I was sae fou,/ Amang the riggs I geed to spew’. Whereas the conventional elegy would commend the subject’s entry into heaven, Ramsay is not so sure about Maggy’s final destination: ‘Guess whether ye’re in heaven or hell,/ They’re sure ye’re dead’.

In ‘Elegy on John Cowper, Kirk-Treasurer’s Man’, Ramsay ironically mourns the death of a lecherous Calvinist, and in ‘Lucky Spence’s Last Advice’, the poet presents the final words of a brothel madam to her prostitutes. It has been argued that Ramsay democratises the genre, making the morally questionable inhabitants of Edinburgh worthy of, albeit ironic, poetic immortalisation.

Ramsay takes on the mantle of Scottish Augustan in many of his poems, and in his ‘Epistle to Arbuckle’, he gives an account of himself and his Augustan aim of order: ‘I hate a Drunkard or a Glutton,/ Yet am nae Fae to Wine and Mutton.’ In ‘The Prospect of Plenty’ and ‘Wealth, or the Woody’, Ramsay continues in this persona, and confidently champions Scotland’s worth within Great Britain.

Throughout his poetry, Ramsay makes great use of traditional Scots forms. In the elegies and elsewhere, he revives the ‘Standard Habbie’ stanza, which takes its name from ‘The Life and Death of Habbie Simpson, the Piper of Kilbarchan’ by Robert Sempill of Beltrees. The ‘Standard Habbie’ becomes so easily recognisable throughout Scottish literature and particularly in Robert Burns, that it has become known as the ‘Burns stanza’. Ramsay also develops the ‘Christis Kirk’ and ‘The Cherry and the Slae’ stanzas, further staples of Scottish literature, and so helps to lend to the Scots tradition an invaluable sense of continuity, and provides permanent classics of the canon.

Ramsay’s play, The Gentle Shepherd (1725), enjoyed massive success both in his lifetime and for several years after his death. This Scots pastoral drama is an entirely original creation, which develops the pastoral genre and fixes it within a Scottish context. Although the play belongs to the sentimental age, its value remains to this day: Ramsay presents his audience with skilful sections of lyric and song, and daringly attempts to revive the Scottish theatrical tradition under the strict codes of Calvinism. The Gentle Shepherd helps make possible John Home’s Douglas, Fergusson’s Scots pastorals and much of Burns’s work.

Ramsay’s role as editor and collector is fundamental to Scottish literature. The Ever Green brought the work of the medieval Scots poets to an audience unfamiliar with their literary heritage, and in The Tea-Table Miscellany (both 1724), Ramsay performed a great service to the preservation of Scottish song. Crucial to these collections is Ramsay’s unwavering belief in Scots as a literary mode, and his conviction that its poetry is worthy of conservation and distribution. In so doing, Ramsay, with his Scoto-Latin, patriotic circle, helped to establish the Scottish literary tradition we study today.

Ramsay’s contribution to Scottish literature is vital on many levels. His role as a bold inventor and developer made much subsequent Scots poetry possible, and his preservation of Scots writing is groundbreaking. In his long, amiable career Ramsay set up worthy expectations for Scots poetry, and brought an unmistakeable sense of humanity to literary modes, which is both poignant and celebratory.

Reading Lists

Primary��

The Gentle Shepherd (1725)

The Tea Table Miscellany (1724)

The Ever Green (1724)

Primary - Collected

Poems by Allan Ramsay and Robert��Fergusson, ed. by��Alexander Manson Kinghorn and Alexander Law��(1974)

The Ever Green, Being a Collection of Scots Poems Written by the Ingenious Before 1600,��2 vols��(1724)

Secondary

Sigrid Rieuwerts, 'Allan Ramsay and the Scottish ballads',��Aberdeen University Review, vol. LVIII, 1, no.201, Spring 1999, pp.29-41

Allan H. MacLaine, 'The Christis Kirk Tradition: Its Evolution in Scots Poetry to Burns, Part III, The Early Eighteenth Century: Allan Ramsay and His Followers,' Studies in Scottish Literature 2 (1965) pp. 163-82

A. M. Kinghorn, 'Watson's Choice, Ramsay's Voice and a Flash of Fergusson,' Scottish Literary Journal 19, no. 2 (1992) pp. 5-23.

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall