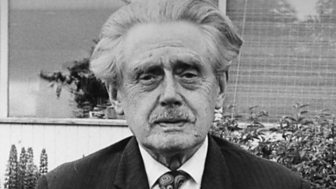

Hugh MacDiarmid

1892 - 1978

Biography

Hugh MacDiarmid was born Christopher Murray Grieve, in the Scottish border town of Langholm in 1892. His father was a postman and the family lived above the town library, so, from childhood, Grieve (or MacDiarmid as he became known from the early 1920s) had unrestricted access to books. This encouraged an interest in reading and in language that would remain with him throughout his life.

Not Burns, Dunbar!Hugh MacDiarmid

Abandoning an early plan to teach, MacDiarmid started out as a journalist, working in Scotland and in Wales before joining the Royal Army Medical Corps on the outbreak of the First World War. Through this he served in Salonica, Greece and France before developing cerebral malaria in 1918 and returning to Scotland. He continued to work as a journalist and, in the 1920s, lived in Montrose where he became Chief Reporter on the local paper as well as serving as a Justice of the Peace and a member of the county council.

However, whilst journalism provided him with a living, MacDiarmid was increasingly interested by developments in contemporary poetry and literature in Scotland (as well as in Europe and Russia) and began to publish a poetry anthology entitled Northern Numbers as well as a literary magazine, Scottish Chapbook, which had as its motto 'Not traditions - Precedents!'’ MacDiarmid was also writing poetry and his first collection, Sangshaw, was published in 1925 with his major work, 'A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle', appearing the following year.

Like many Scottish writers of the early twentieth century, MacDiarmid was fiercely political, and a strong believer in socialism. He felt deeply that Scottish life and culture was ill-served by its political position and, in 1928, was a founding member of the National Party of Scotland - today's SNP. In later years his political stance shifted towards Communism, and, in 1964, he stood as Communist Party candidate against the then Prime Minister, Sir Alex Douglas-Home.

MacDiarmid spent much of the 1930s cut off from mainland cultural developments on the Shetland island of Whalsay, but he continued to write ground-breaking and stylistically innovative poetry, as well as extensive journalism in which he explained his vision for a Scottish renaissance that was both cultural and political. Central to this vision was his belief that the Scottish psyche could not be adequately expressed in the English language alone, and that to develop and write in a synthetic Scots was the only way to achieve a coherent national voice. This was complimented in the 1930s and 1940s when he emphasised the significance of the Gaelic language in Scottish literature and life. His later poetry engages a plurality of voices, languages and forms of expression.

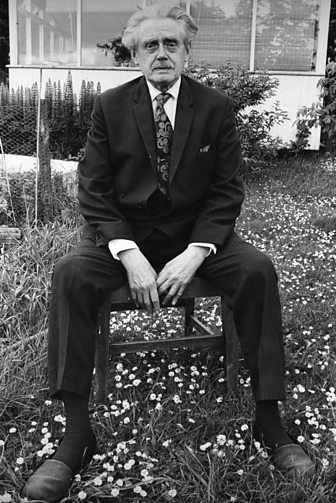

In his later years, MacDiarmid's outlook became increasingly internationalist and the slow but steady growth of his literary reputation allowed him to travel abroad, including visits to the USSR and China. Although he is now recognised as the principle force of the Scottish Literary Renaissance, financial success eluded him for most of his life and his last 27 years were spent living with his second wife Valda at Brownsbank, a cottage (with little in the way of comfort) near Biggar. MacDiarmid died in 1978 and the cottage is now run as a museum and writers' centre.

Works

Hugh MacDiarmid is both the most significant and also the most controversial figure of the Scottish Literary Renaissance, a movement which radically altered the landscape of Scottish writing in the first half of the twentieth century. As well as being a poet of startling innovation and vision, he was also a prolific cultural and political commentator, writing in journals, newspapers and magazines on a vast range of subject matter.

Not traditions - precedents!Hugh MacDiarmid

For many, his best work is to be found among his earliest poems, a group known as the 'early lyrics', which were published in two collections, Sangshaw (1925) and Penny Wheep (1926). Within Sangshaw is MacDiarmid's first Scots lyric poem, 'The Watergaw' (first published in 1922) as well as 'The Bonnie Broukit Bairn', 'Crowdieknowe' and 'The Eemis Stane', while Penny Wheep includes 'The Love-sick Lass', 'Empty Vessel' and 'Focherty'. In these short lyrics, MacDiarmid managed to fuse the language and rhythms of the oral ballads and sense of the older poetic traditions of Dunbar and Burns with an awareness of contemporary developments in modernist European literature, creating rich, symbolic poetry which heralded the reawakening of Scottish literature, and remains as fresh and vivid as at its first appearance.

In the years preceding the appearance of his Scots lyrics, MacDiarmid had begun to evolve a synthetic Scots gathered from many regional variants, and to reclaim archaic language which, once used by the Makars (Scotland's late medieval poets), had fallen from use. This undertaking was a response to what he saw as the linguistic anomaly that the primary language of Scottish literature had become English, a language which he believed could not adequately express the breadth and particularity of the Scottish psyche. This notion was central to the Scottish Renaissance and was shared by many writers of the day although one, Edwin Muir (who is also featured on this website), famously disagreed with MacDiarmid, preferring to accept the linguistic situation as it had developed through time, and continued to write in English, advocating its exclusive use in literature. The dispute between MacDiarmid and Muir went deep into their individual visions of a Scottish renaissance, and they were never reconciled after 1936.

MacDiarmid's use of language can, at first sight, be daunting to the casual reader, for example 'The Watergaw' with its opening line, 'Ae weet forenicht i' the yow-trummle', and his work is often accompanied by a glossary. Clarifying the meaning of 'watergaw' as a shimmering or indistinct rainbow, or the 'yow-trummle' as the spell of cold weather common in Scotland after the summer sheep-shearing, however, reinforces for the reader MacDiarmid's belief in Scots as capable of expression unattainable in English.

'The Watergaw' is an ambiguous lyric, with its cold imagery, 'yow-trummle' 'weet forenicht' and 'on-ding' (or 'downpour') and the suggestions of death as well as cold are present in the image of a smokeless chimney. Death (and atheism) are also evident in the speaker's chilling remembrance, 'An' I thocht o' the last wild look ye gied/ Afore ye died'. Ultimately, the poem raises more questions than it answers and, while it has been interpreted as portraying the death of MacDiarmid's father, it remains essentially private in nature.

In many lyrics, such as 'The Bonnie Broukit Bairn', MacDiarmid's socialist politics come to the fore with the suggestion of the 'broukit' or neglected bairn as the earth, tilting in space, its plight ignored by the wealthy planets in their finery of 'crammasy', 'silk' and 'gowden feathers'. Furthermore, these are images which can also be read in relation to MacDiarmid's nationalist agenda, with the 'broukit bairn' representative of Scotland's suppressed and unfulfilled potential.

MacDiarmid followed his Scots lyrics with 'A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle' (1926), a long dramatic monologue which is considered to be his finest extended work. The 'Drunk Man' is a complex poem and many editions exist, the best of which is Kenneth Buthlay's 1987 edition which provides extensive commentary and notes, leading the reader through MacDiarmid's often opaque use of language. Throughout the 2685 lines of the poem, the drunk man finds himself lying on a moonlit hillside staring at a thistle, which, jaggy yet beautiful, encapsulates the divided Scottish self. Through his inebriation, he considers his national flower, and, speaking aloud in a style close to the modernist 'stream-of-consciousness', muses on the fate of Scotland as nation, on the human condition, and through these, on his own concerns and fears. The depth and complexity of the drunk man's ruminations remind us of the phrase 'in vino veritas', a notion interpreted by MacDiarmid's protagonist with the line, 'there's nocht sae sober as a man blin' drunk' (277).

MacDiarmid's poetry from the 1930s onwards has received little critical attention in comparison to his early lyrics and the 'Drunk Man', although readers may find collections like To Circumjack Cencrastus (1930), First Hymn to Lenin and Other Poems (1931) and Scots Unbound (1932) a more accessible way of approaching his work.

In later years, MacDiarmid continued to write extensively, and became increasingly involved in Communism, a interest that is reflected in poetry such as Second Hymn to Lenin (1935) and the philosophical Stony Limits (1934).

Again in the shadow of his Scots lyrics is his later experimental work which includes In Memoriam James Joyce (1955) and The Kind of Poetry I Want (1961).

Finally, MacDiarmid also published a good deal of prose, of which you may be interested to look at Contemporary Scottish Studies (1926), a collection of essays; Scottish Scene or the Intelligent Man's Guide to Albyn (1934), which he wrote with Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and his magnificent, eccentric autobiography, Lucky Poet, which appeared in 1943.

Reading Lists

Primary

Northern Numbers, 3 vols, ed. by (1920-22)

Annals of the Five Senses (1923)��

Sangschaw (1925)

Penny Wheep (1926)

Contemporary Scottish Studies (1926)

A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle (1926)

Robert Burns 1759-1796, ed. by (1926)

Albyn, or Scotland and the Future (1927)

The Lucky Bag (1927)��

The Present Position of Scottish Music (1927)��

The Present Position of Scottish Arts and Affairs (1928)��

The Scottish National Association of April Fools (1928)

Scotland in 1980 (1929)

The Handmaid of the Lord (1930)

To Circumjack Cencrastus (1930)��

Living Scottish Poets, ed. by (1931)

0 wha's been here before me Lass (1931)

First Hymn to Lenin and Other Poems (1931)

Warning Democracy (1931)

Scots Unbound and Other Poems (1932)

Second Hymn to Lenin (1932)

Tarras (1932)

At the Sign of the Thistle (1934)

Five Bits of Miller (1934)

Scottish Scene or the Intelligent Man's Guide to Albyn with Lewis Grassic Gibbon (1934)��

Selected Poems (1934)��

Stony Limits and Other Poems (1934)

The Birlinn of Clanranald (1935)

Second Hymn to Lenin and Other Poems (1935)

Charles Doughty and the Need for Modern Poetry (1936)��

Scottish Eccentrics (1936)

Direadh (1938)

Scotland and the Question of a Popular Front against Fascism and War (1938)

The Islands of Scotland: Hebrides, Orkney and Shetlands (1939)

Speaking for Scotland (1939)

The Golden Treasury of Scottish Poetry, ed. by (1940)

Cornish Heroic Song for Valda Trevlyn (1943)��

Lucky Poet (1943)

Selected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by R. C. Saunders (1944)

Poems of the East-West Synthesis (1946)

Selected Poems of Hugh MacDiannid (1946)

A Kist of Whistles (1947)

William Soutar: Collected Poems, ed. by (1948)

Robert Burns: Poems, ed. by (1949)

Cunninghame Graham: a Centenary Study (1952)��

as Arthur Leslie, The Politics and Poetry of Hugh MacDiarmid (1952)��

Selections from the Poems of William Dunbar, ed. by (1952)��

Selected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by O. Brown (1954)

Francis George Scott: an Essay on the Occasion of his Seventy-fifth Birthday (1955)

In Memoram James Joyce (1955)��

Selected Poems of William Dunbar, ed. by (1955)

Stony Limits and Scots Unbound and Other Poems (1956)

The Battle Continues (1957)

Three Hymns to Lenin (1957)

Burns Today and Tomorrow (1959)

David Hume: Scotland's Greatest Son (1961)

The Kind of Poetry I Want (1961)

The Blaward and the Skelly (1962)

Bracken Hills in Autumn (1962)

Collected Poems of Hugh MacDiarmid (1962, rev. 1967)

The Man of (almost) Independent Mind (1962)

Poetry Like the Hawthorn (1962)

Robert Burns: Love Songs, ed. by (1962)

When the Rat Race is Over (1962)

The Ugly Birds Without Wings (1962)

An Apprentice Angel (1963)

Harry Martinson: Aniara, a Review of Man in Time and Space (1963)

Sydney Goodsir Smith (1963)

The Ministry of Water: Two Poems (1964)

Six Vituperative Verses (1964)

Two Poems (1964)

The Burning Passion (1965)

Poet and Play and Other Poems (1965)

The Fire of the Spirit: Two Poems (1965)

The Company I've Kept (1966)

Whuchulls (1966)

On a Raised Beach (1967)

The Eemis Stane (1967)

A Lap of Honour (1967)

An Afternoon with Hugh MacDiarmid (1968)

with Owen Dudley Edwards, Gwynfor Evans and Joan Rhys, Celtic Nationalism (1968)

Early Lyrics by Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by J. K. Annand (1968)

The Uncanny Scot (1968)

A Clyack-Sheaf (1969)

Selected Essays of Hugh MacDiarmid ed. by D. Glen (1969)

The MacDiarmids: a Conversation (1970)

More Collected Poems (1970)

Selected Poems, ed. by D. Craig and J. Manson, (1970)

The Hugh MacDiarmid Anthology ed. by M. Grieve and A. Scott (1972)

A Political Speech (1972)

Song of the Seraphim (1973)

Direadh I,II and III (1974)

John Knox, with Campbell Maclean and Anthony Ross (1976)

Complete Poems, 2 vols. (1978)

Lucky Poet: A Self-Study in Literature and Political Ideas, being the Autobiography of Hugh MacDiarmid��(1943)

Recent Editions

The Hugh MacDiarmid Anthology: Poems in Scots and English, edited by Michael Grieve and Alexander Scott. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul [1972].

Selected Poems Hugh MacDiarmid Edited by Alan Riach Carcanet 2002

Annals of the Five Senses Hugh MacDiarmid Edited by Alan Riach Carcanet 1999

Complete Poems Vol I (and II) Hugh MacDiarmid Edited by Alan Riach Carcanet 1993

Secondary

Hamish Hamilton, The Letters of Hugh MacDiarmid��(1984)

Duncan Glen, Hugh MacDiarmid; a critical survey (1972)

Alan Bold John Murray, MacDiarmid: A Critical Biography (1988)

Selected Essays of Hugh MacDiarmid, ed. by Duncan Glen (1969)

Hugh MacDiarmid: Man and Poet, ed. by Nancy Gish (1984)

Gordon Wright, MacDiarmid: An Illustrated Biography of Christopher Murray Grieve (Hugh MacDiarmid) (1977)

The Age of MacDiarmid: Essays on Hugh MacDiarmid and His Influence on Contemporary Scotland, ed. by Paul Henderson Scott and A. C. Davis (1980)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall