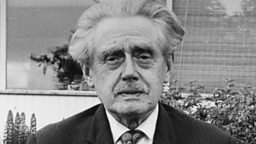

William Soutar

1898 - 1943

Biography

William Soutar was born on 28 April 1898 in Perth, the only son of a close and loving family. He described himself as 'a terrible nuisance' at primary school, but at Perth Academy he excelled at both lessons and sports, fell in love, and began to write poetry. He looked back at his last year of school as one of the happiest times of his life.

When Soutar left school in 1916, World War I was already under way, and he joined the Royal Navy, serving in the Atlantic and the North Sea. During this time he became ill with a form of food poisoning and developed symptoms of pain and stiffness which did not respond to treatment. He was discharged from the Navy in early 1919. He began a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, but soon transferred to study English, graduating in 1923.

By now his health was a continual problem. In 1924 his illness was diagnosed as ankylosing spondylitis, an infection of the spine which had gone too far to be cured. Treatment continued for some years, but after an unsuccessful operation in 1930 he was confined to bed and remained there for the rest of his life.

In 1924 his parents had moved into a newly-built house, 'Inglelowe' ('hearth-glow'), in Wilson Street, Perth. Soutar's father, a master joiner, adapted a downstairs room to make a bedroom with a big window overlooking the back garden. Here Soutar spent the next thirteen years, writing poetry and an extensive journal, and entertaining friends, often several hundred in the course of a year. Many of his visitors were writers and his room has been described as a centre for the Scottish literary renaissance. Diagnosed with tuberculosis in July 1943, he began a new volume of his journal, which he entitled The Diary of a Dying Man. He died on 15th October 1943.

The house 'Inglelowe' was bequeathed by Soutar's father to Perth Town Council, with the condition that Soutar's room should be preserved and shown to 'any interested person ... at all reasonable times'. Now known as the Soutar Hoose, it has for some years been the base for a writer-in-residence, and is used for readings and community events.

Works

For some years after his death, Soutar tended to be regarded as a writer of whimsical children's poetry in Scots, because of his Bairnsangs or Whigmaleeries, such as 'Bawsy Broon' or 'The Three Puddocks' ('Three wee bit puddocks/ Sat upon a stane:/ Tick-a-tack, nick-a-nack,/ Brek your hawse-bane.'). These are short, pithy, often humorous pieces, though many of them have considerable depth. The first Collected Poems (1948), edited by , did not include some of his strongest adult poetry. More recently critics such as Douglas Gifford have come to recognise the wide range and profundity of his work.

Many of his adult poems too are short lyrics which are deceptively simple. Though he was in touch with most of the poets of the , Soutar draws on the whole tradition of Scottish poetry, most notably on the ballads with their hints of a supernatural world which touches this one. Of the images recurring in his work, two are particularly noticeable: the unicorn and the gowk, or cuckoo.

Several of Soutar's greatest poems, such as 'The Auld Tree', contemplate the state of Scotland. In some of them the unicorn appears as a symbol of vision and hope, as in the haunting, ballad-like 'Birthday'. ('It steppit like a stallion,/ Snaw-white and siller-bricht,/ And on its back there was a bairn/ Wha low'd in his ain licht.') It is, of course, one of the supporters on the royal arms of Scotland, but Soutar wrote in his journal in 1938, 'From a purely Scottish emblem the creature has come to represent truth, reality, life under varying aspects but all manifesting the eternal nature of man's quest'.

The symbol of the gowk has a more personal resonance. At first it represents trickery - the cuckoo's traditional role - but later it takes on the gentler but also sadder quality of illusion, and ties in with those poems such as 'The Tryst' which express Soutar's loneliness and unfulfilled desire. These in turn take their place in Soutar's shifting view of his confined environment, from the grim 'Autobiography' and the restriction of 'Reverie' ('The world is shrunk into a little garth') to the rather more sanguine 'The Room' and 'Cosmos': 'There is a universe within this room.' As well as his poetry, Soutar's journals, extracts from which have been published under the title Diaries of a Dying Man, are essential reading. While his unique situation did not make him a writer, there can be little doubt that it evoked some of his most profound and moving work.

Reading Lists

Primary

Gleanings by an Undergraduate (1923)

Conflict (1931)

The Solitary Way (1935)

Brief Words: One Hundred Epigrams (1935)

Poems in Scots (1935)

A Handful of Earth (1936)

Riddles in Scots (1937)

In the Time of Tyrants (1939)

Seeds in the Wind: Poems in Scots for Children (1943)

But the Earth Abideth (1943)

The Solitary Way (1943)

The Expectant Silence (1945)

Collected Poems, ed. by Hugh MacDiarmid (1948) [Incomplete]

Poems of William Soutar: A New Selection, ed. by William Aitken (1988)

Diaries of a Dying Man, ed. by Alexander Scott, (1988)

Into a Room: Selected Poems of William Soutar, eds. Carl MacDougall and Douglas Gifford, (2000)

Secondary

Aitken, W.R., ‘"I’ll Mind Ye in a Sang": William Soutar’s Whigmaleeries’, Chapman 10(4) (1988), pp. 48-50.

‘The Soutar Archives in the National Library of Scotland’, Chapman 10(4) (1988), pp. 46-7

Glen, Duncan, ‘William Soutar’s Prose Writings’, Chapman 10(53) (1989), pp. 2-9.

Goodwin, K.L., ‘William Soutar, Adelaide Crapsey, and Imagism’, SSL 3 (1965), pp. 96-100.

McGregor, Forbes, ‘A Chiel Called Soutar’, Chapman 10(4) (1988), pp. 21-6.

Scott, Alexander, Still Life: William Soutar (1898-1943) (1958)

Related Link

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall