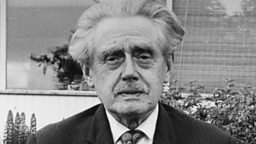

George Douglas Brown

1869 - 1902

Biography

George Douglas Brown was born 1869 in the small village of Ochiltree, Ayrshire. His father was George Douglas Brown, a farmer, who never acknowledged him. His mother, Sarah Gemmel, was a farm-servant of Irish descent. That he was illegitimate may help to explain why some of Brown’s anger was directed at patriarchal neglect, authoritarianism and petty-mindedness in small communities. He was educated at local schools in Ochiltree and Coylton, and attended Ayr Academy from 1883. The rector of Ayr Academy helped Brown gain a bursary to the University of Glasgow, where he graduated with a First in Classics and he received the Snell Exhibition Scholarship to study at Balliol College, Oxford. He played an active role in student life at Oxford, but was also subject to bouts of depression and ill health. He returned to Ayrshire to nurse his dying mother in 1895 and, in consequence, he graduated later that year with only a third class degree.

Later in life (after his mother’s death) Brown moved to London and began a career in journalism. He contributed short fiction and a variety of critical articles to various journals, including an essay on Burns for Blackwood's Magazine. In addition, he provided the glosses for the Scots words in the reprints of ’s novels. In 1899 he published an adventure novel, Love and a Sword under the name ‘Kennedy King’ (he also used the pen name of George Douglas). In the autumn of 1900, he began writing his most famous book, The House with the Green Shutters, which began as a long story about a Scottish character called Gourlay in the small village of Barbie. This was then developed into a novel and was published in 1901 under the name George Douglas. When the book was published, it was well reviewed and received comparisons to works by and John Galt.

Brown planned another novel to be called The Incompatibles, but pneumonia and his already poor health resulted in his death in 1902 at the age of 33. He was buried in Ayr, beside his mother.

Works

The House with the Green Shutters was written as a response to the major changes of industrialism, capitalism and the loss of a spiritual centre in Scotland. When it was published, critics described the novel as an attack on the trend for ‘,’ which offered escape and security in an ever-changing world and catharsis against the pressures of life and a haven from Victorian doubt.

Every clachan in Scotland is a hot-bed of scandal and malevolenceletter to Ernest Barker

Kailyard fiction tended towards stereotypes of Scottish rural life, showing small communities working together to overcome life’s difficulties. In part, Brown’s novel is a reply to the Kailyard myth. In this novel there is no united community, instead there is only cruel gossip, the failure of youth and a yawning absence of faith in anything. Lacking the perspective of any social or spiritual context with which to view the world, Brown’s fictional village, ‘Barbie’, which may have been based on Ochiltree, has retracted to social competition. It is a nest of jealousy and spite, often expressed in the ‘barbed’ comments of the ‘bodies’ or local gossips. They are, as Brown phrases it, the ‘big men in the small world’.

Gourlay is the black cavity at the centre of that diseased society. The people resent Gourlay’s success, which is symbolised by his imposing house with the green shutters. Yet they fear him; he is the most successful among them because the desire for power and domination are greatest in him.

He is portrayed as a devil-like figure with almost demonic powers. This demonic figure can be traced in the writing of , , and R. L. Stevenson. The effect of this ‘unnatural’ driving force is that Gourlay strips the community of its own force and dignity. There is no ‘God as Father’ in the novel, no House of God, only Gourlay the patriarch and the House of Gourlay. The church exerts no influence in Barbie. The community is emasculated, divested of its own power: moral or otherwise. It is a community characterised by ‘gossipy’ or effeminate men who live in various states of fear. These ‘bodies’ are described as ‘old maids’ with ‘impotent’ power.

There is beauty in the novel but the tragedy is that the community, cut off from the powerful sources of natural order, are blind to it. Instead they are trapped by the small-minded insecurities of a society reigned in by a longing for money, progress and power. Brown blames this introverted lack of perspective upon the cult of individualism. His comments on ‘the Scot’ are rarely complementary.

Gourlay’s symbolic house is grand and orderly on the outside but chaotic within. Mrs Gourlay dotes on her son, so Gourlay, to spite her, rejects and criticises him. Stifled by maternal love and paternal domination, Gourlay Junior learns to stand in awe of his father’s wrath but to be fearful of life itself. He has an overdeveloped mental perception but his imagination is not a source of fertility and creativity. Instead, it is as barren as the desolate landscape depicted in the story he writes. The house has no fireplace, no warm hearth, no family heart, only ‘the gaping place where the warmth should have been.’ Temperamentally unstable, young Gourlay slides into alcoholism, and provoked by the ‘bodies’, murders his father in a fit of drunken resentment.

There are moments of redemption in the novel. Beauty and softness are there, but they are thwarted by pride and greed. The creation of the novel itself, the use of language and the structure all emphasise that creativity is not dead. The novel concludes that the house is the diseased heart of a society which no longer perceives external beauty. Yet, in the final sentence, there is a sense of hope; the house with the green shutters still blights the landscape but its inhabitants are all dead through murder or disease, and in its final, impotent artfulness, it sits beneath ‘the radiant arch of the dawn.’

Quotes

Gourlay felt for the house of his pride even more than for himself – rather the house was himself; there was no division between them. He had built it bluff to represent him to the world. It was his character in stone and lime. He clung to it, as the dull, fierce mind, unable to live in thoughts, clings to a material source of pride.’

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 24

’Tis a brutal and a bloody work... There is too much black for the white in it. Even so it is more complimentary to Scotland, I think, than the sentimental slop of Barrie, and Crockett, and Maclaren. It was antagonism to their method that made me embitter the blackness; like Old Gourlay I was going to ‘show the dogs what I thought of them.’ Which was a gross blunder, of course. A novelist should never have an axe of his own to grind.letter to Ernest Barker

If a man’s success offends your individuality, to say everything you can against him is a recognised weapon of the fight. It takes him down a bit. And (inversely) elevates his rival.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 24

To break a man’s spirit so, take that from him which he will never recover while he lives, send him slinking away animo castrato – for that is what it comes to – is a sinister outrage of the world. It is as bad as the rape of a woman, and ranks with the sin against the Holy Ghost – derives from it, indeed.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 25

When the Deacon was not afraid of a man he robbed him on the straight. When he was afraid of him he stabbed him on the fly.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 2

Mrs Gourlay raised her arms, like a gaunt sibyl, and spoke to her Maker, quietly, as if He were a man before her in the room. ‘Ruin and murder,’ she said slowly; ‘and madness; and death at my nipple like a child! When will Ye be satisfied?’

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 26

They gazed with blanched faces at the House with the Green Shutters, sitting there dark and terrible, beneath the radiant arch of the dawn.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 27

There is a megalomaniac in every parish of Scotland. Well, not so much as that; they’re owre canny for that to be said of them.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 11

In every little Scotch community there is a distinct type known as ‘the bodie’. ‘What does he do, that man?’ you may ask, and the answer will be, ‘Really, I could hardly tell ye what he does – he’s juist a bodie!’

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 5

No man has a keener eye for behaviour than the Scot.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 5

The Scot, as pundits will tell you, is an individualist. His religion alone is enough to make him so. For it is a scheme of personal salvation significantly described once by the Reverend Mr Struthers of Barbie. ‘At the Day of Judgement, my friends,’ said Mr Struthers; at the Day of Judgement every herring must hang by his own tail!’ Self-dependence was never more luridly expressed. History, climate, social conditions, and the national beverage have all combined (the pundits go on) to make the Scot an individualist, fighting for his own hand. The better for him if it be so; from that he gets the grit that tells.

The House with the Green Shutters, ch. 5

Reading Lists

Primary

The House With the Green Shutters (1901)

Secondary

Campbell, Ian. 'George Douglas Brown: A Study in Objectivity.' In Nineteenth-Century Scottish Fiction: Critical Essays (1979) pp. 148–163

Campbell, Ian and Vogel, Brian 'The House with the Green Shutters and the Seeing Eye' Studies in Scottish Literature 27, 1992. pp. 89-104

Hart, F.R. The Scottish Novel: A Critical Survey (1978) See chapter 7, 'The Anti-Kailyard as Theological Furor'

Royle, Nicholas. 'The Ghost of Hamlet in The House with the Green Shutters.' Studies in Scottish Literature 27, 1992. pp. 105-112

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall