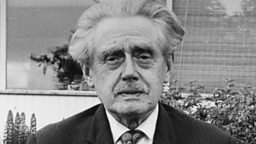

Neil Munro

1863 - 1930

Biography

The novelist, poet and journalist Neil Munro (1863-1930) was the illegitimate son of a kitchen maid and many believe his father to be a member of the aristocratic Argyll family. After he left Inveraray School at thirteen he worked in the office of the Sheriff-Clerk of Argyll, before leaving the Highlands to pursue a career in journalism in 1881.

A short story collection, The Lost Pibroch and Other Sheiling Stories, appeared in 1896 and his first novel John Splendid was published in 1898. This was followed by a number of historical novels all exploring the impact of change within the Highlands. Doom Castle (1901) and The New Road (1914) focus on the contrast between the Highlands and the South of Scotland, the Gaelic speakers and the English. Both his mother and grandmother were Gaelic speakers and Munro’s affection for the language is perceptible. It is used for terms of endearment and emotion and runs throughout the novels. Munro speaks of the Highlands as one who laments the changes while understanding the benefits. Such novels were acknowledged as prime models of the genre.

Munro went on to achieve worldwide fame. In his prime he was editor of the Glasgow Evening News and was generally regarded as being a senior figure in contemporary Scottish criticism and a dominating presence in Scottish letters. He wrote on European art, Glasgow policies and the Highlands, providing a first hand commentary on the Scottish social situation. He saw Glasgow as being the second city of the Empire with the importance of the Clyde Ships, Charles Rennie MackIntosh and the Great Exhibition.

Around 1902 Munro retired from full-time journalism, but continued a weekly column in the News which was to prove extremely popular with the readers. There were three light-hearted short stories published under the name ‘Hugh Foulis’ (a pseudonym which functioned to distinguish these from his more serious work) Erchie, My Droll Friend (1904), Jimmy Swan, the Joy Traveller (1923) and Para Handy Tales (1958).

He made a temporary return to full-time journalism during World War One. However, sadly he lost his son Hugh in the war and after this he was to produce little new material.

Munro is major writer who has been underestimated in recent years and is now best known for stories in his newspaper column. Despite being described as ‘the apostolic successor of Sir Walter Scott’, Munro’s reputation suffered posthumously, the archaic style of the novels playing some part in this. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been an upsurge in interest towards this great writer and with his works again in print, it is likely that he may be restored to his former status.

He is buried in Kilmalieu Cemetery, Inveraray and a monument to his memory was erected in Glen Aray in 1935.

Works

Munro’s historical novels were valued in their time as much as the work of Walter Scott or R. L. Stevenson before him. Since then they have often been overlooked as mere romance novels. This fails to recognise that Munro’s novels, like Stevenson’s, often contain a dark satirical and thematic undercurrent.

Gilian the Dreamer (1899) belongs to a similar tradition as Walter Scott’s Waverley (1814). Both feature protagonists whose imagination is so intense that they cannot commit to action. Set in Inverary during the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, the community in that novel finds no place for the imagination. The people see Gilian as a failure because, like J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, he often chooses imagination and fantasy over reality. The novel is as much a criticism of a society which cannot find a place for the imagination as of the protagonist himself. Previously Gilian may have had a place within the Gaelic tradition as a bard. However, the time for such traditions has passed and his gifts are seen to restrict his growth into maturity. Gilian’s ‘lonely and unusual’ childhood is very similar to Munro’s own experience. Munro felt that Scotland’s male-dominated culture marginalised creative thought consequently stifling the artist and writers. Women such as Nan and Miss Mary are shown to stimulate and sympathise with the imagination. It is with them that Gilian can relate but as a result the men reject him.

His novels display both an admiration for the military values of martial Gaeldom as well as disgust at the unnecessary slaughter that comes out of barbaric action. His final novel, The New Road, is perhaps his most accomplished work in this genre. Set in 1733, when General Wade opened the Highlands to trade with the Lowlands, the novel attacks the corruption at the heart of the Highlanders and depicts characters such as the blackmailer Barisdale and the evil Lord Lovat who symbolise the corruption and betrayal within the clans. The novel keeps the suspense going throughout and it is not until the final page that the truth about Æneas’s father, Paul, and the true treachery of Duncanson, is revealed.

Munro looks at an actual period of history in The New Road to discuss the implications of history and of change. Through the negative portrayal of Highland treachery, the road comes to stand for a much-needed symbol of order and regulation. The Highlanders reject it because it threatens their hold of the land. Yet, ironically, the road is also serving the Highlanders. The road allows a new commodity of power to enter into the politics of the North and the battles of blood are turned into battles for money. The main regret about the road is that it is seen to desecrate a landscape once wild and free. As such, it is often symbolised as a ‘scar’ or ‘trench’. Æneas reflects on his journey home that even though the road guarantees his safety, he still loves the passion and adventure of the old lands. He is to be disabused of his romantic fantasy of the Highlands throughout the novel. When he sets off on his journey it is a Highlands of adventure and romance, but he is forced to recognise that the ‘heroic’ men are actually shallow blusterers fighting over petty crimes.

His first novel, John Splendid (1898), sets up many themes that reoccur throughout Munro’s work. Like the others, it is set in a period of social change. It focuses on the sack of Inveraray by Montrose and his victory at the Battle of Inverlochy, 1645. The protagonist of the title is loyal to his clan chief whose actions and demands are those of a coward. Munro’s depiction of the clans is often satirical, commenting that that it is proof of manhood to butcher and slaughter the innocent. Splendid eventually realises that his loyalty is misplaced, and he abandons his Chief to become a mercenary soldier.

Munro’s depiction of the Highlands, as we have seen, is not always a sympathetic one. His short story collection The Lost Pibroch and Other Sheiling Stories draws from the folktales of the Highlands but is also a satirical response to romanticised and self-indulgent notions of the Highlands. The title tale tells of an ancient pipe that if played will bring bad luck and darkness down on the Highlands. The young men will leave the country and take with them the hope for new life. The other stories in the collection demonstrate, ironically, that the pibroch has already been played: the son kills his unknown father, clans and communities come to bloodshed over foolish feuds often started with a minor insult. Artists are literally or metaphorically rejected from the community, often blind or crippled, they are doomed to be outsiders.

The change to stories of the Lowlands reflects Munro’s own move south from the Highlands. The Para Handy stories have became popular with their light hearted social commentary on contemporary issues. The characters avoid work at any cost and continually get themselves into scrapes. The adventures of the West Highland puffer skipper and the crew of the coaster Vital Spark have enjoyed continuing success and have been adapted for television, stage and film.

Reading Lists

Primary

The Lost Pibroch, and Other Sheiling Stories (1896)

John Splendid: the Tale of a Poor Gentleman and Little Wars of Lorn (1898)

Gilian the Dreamer (1899)

The Shoes of Fortune (1901)

Doom Castle: A Romance (1901)

Children of Tempest: A Tale of the Other Isles (1903)

Erchie, My Droll Friend [by H(ugh) F(oulis)] (1904)

The Vital Spark and her Queer Crew [by H.F.] (1906)

The Clyde, River and Firth (1907)

The Daft Days (1907)

Fancy Farm (1910)

In Highland Harbours with Para Handy, s.s., Vital Spark [by H.F.] (1911)

Ayrshire Idylls (1912)

The New Road (1914)

Jaunty Jock and Other Stories (1918)

Jimmy Swan, the Joy Traveller [by H.F.] (1923)

Hurricane Jack of the Vital Spark [by H.F.] (1923)

The Poetry of Neil Munro, introduced by John Buchan (1931)

The Brave Days: A Chronicle from the North, ed. by George Blake (1931)

The Looker-On, ed. by George Blake (1933) (essays)

Para Handy Tales (1958)

Para Handy, First complete edition, ed. by Brian D. Osborne and Ronald Armstrong (1991)

Erchie and Jimmy Swan, First complete edition, ed. by Brian D. Osborne and Ronald Armstrong (1993)

Secondary

Hart, Francis, The Scottish Novel (1978)

Völkel, Herman, Das Literarische Werk Neil Munros (1994)

See also lengthy introductions to recent editions, above.

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall