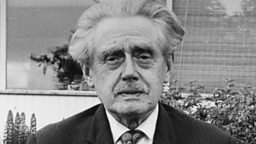

Alasdair Gray

1934 -

Biography

Describing himself as a ‘maker of imagined objects,’ Alasdair Gray has been a prolific producer of novels, short stories, plays, poems, pamphlets and literary criticism. He is also an accomplished artist who has painted remarkable murals and is the designer and illustrator of his own books and those of other writers.

Alasdair James Gray was born on 28 December 1934. At the age of five he was evacuated to Lanarkshire along with his mother and younger sister before being reunited with his father in Wetherby, Yorkshire, in 1941. After the war the family returned to Glasgow where Gray attended Whitehill Senior Secondary School. As a teenager Gray wrote a version of one of Aesop’s fables which he read, along with some poems, on a ����ý children’s programme. At the same time he was writing and drawing pieces which appeared in the Whitehill School Magazine. After leaving school Gray studied at Glasgow School of Art where he specialised in murals. His experiences as a child and young adult in Glasgow would later form the basis for books One and Two of Lanark, his first and still his best known novel.

After graduating Alasdair Gray taught art in Lanarkshire and painted murals in churches and a synagogue. Many of these murals were lost when the buildings were destroyed, but some, together with Gray’s later work, still survive. Between 1960 and 1962 Gray worked as a scene painter in the Glasgow Pavilion and Glasgow Citizens theatres and from 1977 until 1978 he was employed as artist-recorder at Glasgow’s People’s Palace. In the 1960s and 1970s Gray wrote plays for radio, television and stage, many of which would be revised and reappear later in prose form. During this time Gray continued to work on the novel which would eventually be published as Lanark in 1981. Gray attended Philip Hobsbaum’s Glasgow writers’ group, along with fellow Glaswegians and .

Since 1981 Gray has worked mostly as novelist and short story writer. He has also worked as a writer in residence and later Professor of Creative Writing, along with James Kelman and Tom Leonard, at the University of Glasgow. A well known socialist and supporter of Scottish independence, Gray’s activism extends beyond the covers of his books, protesting against nuclear weapons at Faslane and against the second Gulf War in 2003.

(last updated in September 2004)

Works

When Alasdair Gray’s first novel, Lanark: A Life in 4 Books was published in 1981, it was met with immediate critical acclaim. Lanark is set partly in the Glasgow of the 1940s and 1950s and partly in a nightmarish otherworld where the normal rules of reality appear, like almost everything else, to have broken down. The novel begins, unusually, with Book Three, where Lanark arrives in the city of Unthank having lost his memory, and finds that he is developing Dragonhide, a disease which makes his skin scale over the longer he remains there. He is eventually swallowed by a huge mouth which opens in the ground of the city necropolis and finds himself recovering in the Institute, where he is told about his earlier life as a boy and young man in Glasgow.

Books One and Two then tell the story of Duncan Thaw’s childhood and young adulthood as a Glaswegian art student who eventually drops out of the Art School and suffers a breakdown while painting a mural based on the book of Genesis in a Glasgow church. In Book Four the story returns to Lanark and Rima in the Institute. On their journey back to Unthank, Rima gives birth to a son. Lanark finally awaits his death having failed to negotiate a better deal for the people of Unthank as the city’s provost.

No such summary can do justice to Gray’s achievement in Lanark, a novel which Iain Banks described as ‘the best in Scottish literature this century’. Lanark attempts to take a familiar landscape and to make it strange again, asking us to look at the world around us with fresh eyes. It is also a highly political novel. The Institute, where people survive by eating the flesh of its patients, provides an allegory for the capitalist world order at the end of the twentieth Century.

Gray has described his second novel 1982 Janine (1984) as his best. It follows ’s long poem A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle in describing ‘The matter of Scotland refracted through alcoholic reverie’ (1982 Janine, 343). In 1982 Janine, John McLeish, an alcoholic security professional, lies on his hotel bed constructing elaborate sexual fantasies in an attempt to block out painful memories from his own life. John’s fantasies are described cinematically, with John himself in the role of a pornographic film director. As 1982 Janine progresses, John is unable to prevent his memories from resurfacing and forcing him to confront his relationships with his parents, his former love affairs and failed marriage. The sexual fantasies in 1982 Janine have embarrassed many critics, contributing to the novel’s relative neglect when compared to Lanark. The frankness with which the novel discusses these fantasies, however, draws attention to those things which cannot be talked about openly. As McLeish himself says, ‘My problem is sex, or if it isn’t, sex hides the problem so completely that I don’t know what it is’ (1982 Janine, 16).

1982 Janine is, despite its affirmative conclusion, perhaps Gray’s bleakest novel. It is set in the middle of the Cold War at a time when the British old Left was fighting the free market politics of Thatcherism for its very survival. Refusing any return to ‘family values’, Gray’s second novel insists that ‘the personal is political’, using the devices of pornography to explore the different ways in which people are used, abused and restrained by others, and by the systems within which they are forced to live. 1982 Janine is also a novel about being a man in late twentieth century Scotland, struggling to adjust to changes in male roles brought about by the advances of feminism and the decline of heavy industry.

In 1985 Gray published his third novel, The Fall of Kelvin Walker. This parable-like tale of a power hungry Scot on the make in London had appeared in various previous incarnations, the earliest being a television play broadcast by the ����ý in 1968. Its central character is the youngest son of a Presbyterian minister from Glaik, who becomes a prominent political broadcaster and newspaper columnist. The novel explores Kelvin’s relationship with Jake and Jill, the free living couple whom he takes up with in London, to ask questions about the way people’s personalities are formed and how this determines their relationships with their surroundings.

Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D. Scottish Public Health Officer (1992), is a Scottish Frankenstein story in which a pregnant woman is fished from the Clyde after attempting suicide only to have her unborn child’s brain implanted into her own skull. In the central narrative Archibald ‘Candle’ McCandless tells the fantastic story of Bella Baxter’s rebirth at the hands of his outcast friend, the scientist Godwin ‘God’ Baxter, a character from the pages of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein or ’s Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde. Bella’s subsequent elopement and voyages around Europe are told in a series of letters which McCandless reproduces. The whole thing is then dismissed as a fabrication in a letter by the novel’s heroine. Poor Things is Gray’s most extended exploration of Scotland’s Imperial history.

A History Maker (1994) is set in a twenty-third century matriarchal society in the Borders of what used to be Scotland. Capitalism and the nation state have been abolished, and war has been replaced with highly ritualised war games in which Gray’s twenty-third century Border clans fight it out in front of ‘public eyes’, which relay the games to the rest of the world. Gray’s hero, Wat Dryhope, is bored with living in a world where History is a thing of the past, and becomes involved with Delilah Puddock, one of a number of conspirators plotting to return the world to its pre-utopian state.

(Last updated in September 2004)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall