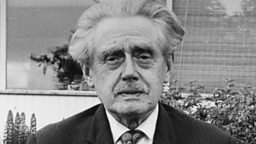

Liz Lochhead

1947 -

Biography

Liz Lochhead was born in Motherwell, Lanarkshire in 1947. She attended the Glasgow School of Art between 1965 and 1970 and, after graduation, worked as a teacher of fine art in Glasgow and Bristol, a career at which she claims to have been “terrible”.

During the 1970s Lochhead was a member of the prestigious writer’s group initiated by Philip Hobsbaum and which included the new talents of , and . During this period Lochhead was also putting her considerable talents to good use in the collection of poems that would later be published as Memo for Spring (1972) and which received a Scottish Arts Council Book Award.

Shortly afterwards, in 1978, Lochhead made her first venture into drama with her revue, Sugar and Spite. In this same year her award of the Scottish/Canadian Writers Exchange Fellowship allowed Lochhead to abandon teaching for writing full-time. In 1986 Lochhead married the architect, Tom Logan, and they made Glasgow their home.

During her career Lochhead has been described variously as a poet, feminist playwright, translator and broadcaster but has said that ‘when somebody asks me what I do I usually say writer. The most precious thing to me is to be a poet. If I were a playwright, I’d like to be a poet in the theatre.’ Lochhead’s careers as poet and playwright have always been co-existent. Between 1986-7 she was Writer in Residence at Edinburgh University and a year later Writer in Residence for the Royal Shakespeare Company.

In 1981 Lochhead’s third collection of poems, The Grimm Sisters was published and in 1982, her first full-length play, Blood and Ice was performed at the Edinburgh Traverse. Dreaming Frankenstein and Collected Poems (1984) was followed in 1985 by True Confessions and New Cliches.

During the 1980s, Lochhead produced the plays that were to make her name as a Scottish playwright: the critically acclaimed Scots translation of Moliere’s Tartuffe, Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off (which was performed at the Edinburgh Festival in 1987) and Dracula (1989).

The 1990s saw a move away from the more overtly feminist agenda of Lochhead’s early works and into a wider concern with issues of voice in general. 1991 saw the publication of Bagpipe Muzak and a movement into film with the ����ý screening of Lochhead’s short film Latin for A Dark Room as part of the Tartan Shorts series. More recently, her adaptation of Euripedes’ Medea won the 2000 Saltire Scottish Book of the Year Award and in that same year she was awarded an honorary literary degree from the University of Edinburgh. She has also adapted Moliere’s The Misanthrope into a satire on the modern Scottish Parliament in the play, Miseryguts (2002), and another collection of poems, The Colour of Black and White was published in 2003.

(Last updated in September 2004)

Works

The work of Liz Lochhead, like that of her friend and contemporary, Tom Leonard, evinces an interest in voice and the political aspects of articulation. Lochhead’s poetry is characterised by its intimate address and unpretentious style in work that self-consciously seeks to mimic the idioms of speech. Her poetry adopts a range of spoken styles that include the lyrical use of cliché, advertising language, rap and colloquialisms.

Like Leonard, Lochhead recognises that the act of speech is in itself political, and her poetry seeks to give expression to both the marginalized voices of Scots and the community of women. Indeed, Lochhead has said, “My language is female-coloured as well as Scottish-coloured.”

‘Kidspoem/Bairnsang’ in her 2003 collection, The Colour of Black and White, reveals Lochhead’s continuing concern with the validity of the Scots voice. The poem describes the way in which Scots is rejected as a valid form of written expression and sidelined into informal, spoken usage:

Oh saying it was one thing

but when it came to writing it

in black and white

the way it had to be said

was as if you were posh, grown-up, male, English and dead.

In the poem ‘Liz Lochhead’s Lady Writer Talkin’ Blues (Rap)’ from True Confessions and New Cliches (1985), Lochhead writes of the implicitly provocative act of being a female writer:

He said Mah Work was a load a’ drivel

I called it detail, he called it trivial

Tappin’ out them poems in mah tacky room

About mah terrible cramps and mah

Moon Trawled Womb –

Women’s trouble?

Self Pity.

Here Lochhead satirises stereotypical male judgements about so-called ‘women’s writing’ (and she does so, notably, in a colloquial, spoken Scots voice).

One of the principal ways Lochhead has demonstrated her interest in female identity and in women’s writing is through the playful and ironic re-writing of traditional myths about women. The Grimm Sisters (1981) features a whole cast of ‘stock characters’ or stereotypes of women: the ‘spinster’, the ‘bawd’, the ‘harridan’, who are enabled to speak for themselves in these poems, from the female point of view. In poems such as ‘Repunzstiltskin’ Lochhead plays with the myths of Rapunzel: the trapped and helpless female, and Rumplestiltskin; the aggressive, self-serving male, to mock the injustices of conventional male power in romantic relationships:

& just when our maiden had got

good & used to her isolation,

stopped daily expecting to be rescued,

had come almost to love her tower,

along comes This Prince

with absolutely

all the wrong answers.

In poems such as these the style is typically casual, even flippant, as if the narrator is wearily recording a story she has told too often.

In ‘Mirror’s Song’ from Dreaming Frankenstein (1984) Lochhead discusses the complex relationship between a woman and her appearance in a poem that challenges women to abandon their self-restricting conventional roles: "Smash me looking glass glass/coffin, the one/that keeps your best black self on ice." Women in modern society are literally frozen into static one-dimensional images that the poet-narrator urges her readership to break down. In this way, Lochhead’s poetry is concerned with specifically female issues and the critical scrutiny of the social roles assigned to women in a Scots-English poetry that is bold, contemporary and down-to-earth.

The best-known and most critically acclaimed of Liz Lochhead’s dramas, Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off, was published in 1989 alongside her lesser-known play Dracula. In Mary Queen of Scots, Lochhead sought to dramatise the religious and political history of Scotland from the female point of view. The play is therefore concerned with the rule of two Queens, Elizabeth of England and Mary of Scotland, during the sixteenth century and the various expectations and restrictions confronting women in power at that time.

Lochhead is concerned with the ways in which femininity is constructed and performed and she has the character of Elizabeth enact masculine types of behaviour (even appearing on stage in men’s clothes) as a means of representing the exclusion of feminine behaviour in the political realm. Mary, by contrast, wields a more conventionally feminine power, exploiting her sexuality and the emotional vulnerability associated with her sex in order to get her own way. Lochhead is particularly concerned with the relationship between Mary and the Scottish religious reformer John Knox, who viewed Mary, and women in general, as dangerous, sexually potent and potentially subversive entities, unfit for spiritual or political leadership. In examining the relationship between Mary and Knox, Lochhead seeks to investigate the roots of anti-feminism in the Scottish Church. Ultimately, Mary’s tragic end at the hands of the aristocracy, and with the complicity of Queen Elizabeth, is portrayed as representative of the ways in which women have been excluded from, and corrupted by, masculine institutions of power.

(Last updated in September 2004)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall