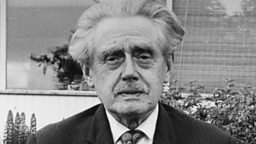

Sorley MacLean

1911 - 1996

Biography

Sorley MacLean was born at Osgaig on the island of Rasaay on 26 October 1911. He was brought up within a family and community immersed in Gaelic language and culture, particularly song. He studied English at Edinburgh University from 1929, taking a first class honours degree and there encountering and finding an affinity with the work of , Ezra Pound, and other Modernist poets. Despite this influence, he eventually adopted Gaelic as the medium most appropriate for his poetry. However, it should be noted that MacLean translated much of his own work into English, opening it up to a wider public than the some 80,000 speakers of the Gaelic language.

During the Spanish Civil War, MacLean was torn between family commitments and his desire to fight on behalf of the International Brigades, illustrating his left-wing - even Marxist - political stance. He eventually resigned himself to remaining on Skye. He fought in North Africa during World War Two, before taking up a career in teaching, holding posts on Mull, in Edinburgh and finally as Head Teacher at Plockton High School.

It is often said that what Hugh MacDiarmid did for Scots, Sorley MacLean did for Gaelic, sparking a Gaelic renaissance in Scottish literature in line with the earlier '', as evinced in the work of George Campbell Hay, Derick Thomson and . Moreover, he was instrumental in preserving and promoting the teaching of Gaelic in Scottish schools. Through the diverse subject matter of his poetry, he demonstrates the capacity of the Gaelic language to express themes from the personal to the political and philosophical.

MacLean's work was virtually unknown outside Gaelic-speaking circles until the 1970s, when Gordon Wright published Four Points of a Saltire - poems from George Campbell Hay, Stuart MacGregor, William Neill and Sorley MacLean. He also then appeared at the Cambridge Poetry Festival, establishing his fame in England, as well as Scotland and Ireland, where he had become something of a cult figure thanks to a fan base including fellow poet Seamus Heaney. A bilingual Selected Poems of 1977 secured a broader readership and a new generation began to appreciate his work.

Latterly, he wrote and published little, showing his concern with quality and authenticity over quantity. Never a full-time writer, he was also a scholar of the Highlands with a vast knowledge of genealogy, and an avid follower of shinty. Amongst other awards and honours, he received the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry in 1990. He passed on in 1996 at the age of 85, and was survived by his wife and two daughters.

Works

MacLean's body of work is relatively small due to his prioritising of merit and authenticity over output. Perhaps his finest work is to be found in the sequence of themed poems, Dain Do Eimhir agus Dain Eile/ Poems to Eimhir and Other Poems (1943). Written mostly during the 1930s, the sequence consists of forty-eight love poems given Roman numerals, plus a closing 'Dimitto', and a final section of 'dain eile'. They address a universal 'eimhir', or woman, but these love poems also comprise sharp political invective and Modernist reflections on subjectivity.

Political commitment and love are intertwined in number XXII of the sequence, 'An Roghainn'/'The Choice'. The poet confronts a paradox here, that by not going to fight in the Spanish Civil War, he has made himself unworthy of eimhir's love, yet if he had gone he would surely have been killed: 'I did not take a cross's death/ in the hard extremity of Spain/ and how then should I expect/ the one new prize of fate?'

Another of the sequence, number XLV 'An Sgian'/'The Knife', represents a Modernist concern with the fragmentation of the self. An internal dialogue takes place between head and heart, concluding with the illogical but unyielding nature of love.

Number XXIX of the sequence, 'Dogs and Wolves', has been published separately (such as in 17 Poems for 6d (1940)), and does indeed stand alone, as many from the sequence do. The cruel and violent imagery of the hunting, 'bloody-tongued' animals, 'in chase of beauty', or eimhir, refers to MacLean's 'unwritten poems'. Yet these notions are abstract and open to varying interpretations. Will the poems ever be written? If they are potentially so fierce, should they yet be articulated? The hunt is, we are told, 'without halt, without respite.' Will they, then, never catch their prey? This paradox ensures beauty's survival.

A later poem '', first published in the Gaelic journal Gairm in 1954, is an intense meditation on the effects of the . However, the Clearances are never actually explicitly cited in the poem, rather the build-up of allusion and atmosphere indicate what has taken place in this settlement, originally to be found on MacLean's home island of Raasay, and cleared between 1852 and 1854. The epigraph to the poem, 'Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig', indicates the otherworldly quality of what we are about to encounter from the outset, and half way through, the poet eerily tells us that in Hallaig, 'the dead have been seen alive.'

The dead are tangible monuments to history, showing that the past refuses to be forgotten. The tone is elegiac throughout, mourning the passing of youth, 'beauty', and 'laughter' from this place. However, there is a shift towards the final stanza, when we are told that, 'a vehement bullet will come from the gun of love;/and will strike the deer that goes dizzily ... /his eye will freeze in the wood,/his blood will not be traced while I live.' The time that divides the poet from when this place was alive and inhabited can be elided in a bloodless killing. The poet will make the people of Hallaig immortal.

Another longer, although unfinished, poem is 'An Cuilithionn'/ 'The Cuillin', which MacLean worked on from 1939 to 1940. The Cuillin mountain range on Skye becomes an ambivalent symbol, representing both the indomitable human spirit and beauty, and destruction and desolation. The poem refers to both the people of Skye, who have suffered poverty and exile, and the people of the world, who have undergone similar fates, such as the Spanish workers during the Spanish Civil War. Skye becomes synecdoche for world struggle, and this universal perspective and sympathy is apparent in much of MacLean's work. However, in this poem, both destruction and redemption are possible.

MacLean also wrote numerous war poems, amongst which is the 1965 'Heroes'. The poem is a kind if tongue-in-cheek homage to a reluctant hero, a 'little', 'chubby', and 'pimply' but brave English soldier whose death MacLean witnessed in Egypt during World War Two. The poet calls him 'a great warrior of England', yet then goes on to suggest - perhaps ironically - that he does not match up to 'Alasdair of Glengarry', a legendary hero from the Gaelic past. There is no glory for this unlikely hero, just the harsh reality of war, the absurdity accepted. His death is a necessary evil, and although he will win 'no cross or medal ... or any froth from the mouth of the field of slaughter', the poet will instead honour him.

Reading Lists

Primary��

Spring Tide and Neap Tide: Selected Poems 1932 – 1972��(1972)��

17 poems for 6d with (1940)

Ris a’Bhruthaich: The Criticism and Prose Writings of Sorley MacLean (1985)

Poems 1932 – 1982 (1987)

O choille gu bearradh (From Wood to Ridge): Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation��(1999)

Dain do Eimhir,��ed. by Christopher Whyte��(2002)

Secondary

Sorley MacLean : critical essays, ed. by Raymond J. Ross and Joy Hendry (1986)

Related Links

Writing Scotland themes

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall

-

![]()

by Carl MacDougall